CHAPTER 4: ATMOSPHERIC MOTIONS and TRANSPORT - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

Title:

CHAPTER 4: ATMOSPHERIC MOTIONS and TRANSPORT

Description:

CHAPTER 4: ATMOSPHERIC MOTIONS and TRANSPORT WHAT ARE THE FORCES BEHIND ATMOSPHERIC CIRCULATION? Global Circulation as a Giant Sea Breeze. Concepts: Pressure Gradient ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:107

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: CHAPTER 4: ATMOSPHERIC MOTIONS and TRANSPORT

1

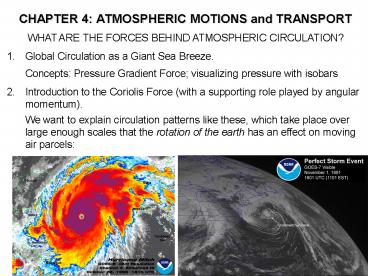

CHAPTER 4 ATMOSPHERIC MOTIONS and TRANSPORT

- WHAT ARE THE FORCES BEHIND ATMOSPHERIC

CIRCULATION? - Global Circulation as a Giant Sea

Breeze.Concepts Pressure Gradient Force

visualizing pressure with isobars - Introduction to the Coriolis Force (with a

supporting role played by angular momentum).We

want to explain circulation patterns like these,

which take place over large enough scales that

the rotation of the earth has an effect on moving

air parcels

2

CHAPTER 4 ATMOSPHERIC TRANSPORT

- Forces in the atmosphere

- Gravity

- Pressure-gradient

- Coriolis

- Friction

to R of direction of motion (NH) or L (SH)

Equilibrium of forces

In vertical barometric law In horizontal

geostrophic flow parallel to isobars

gp

P

v

P DP

gc

In horizontal, near surface flow tilted to

region of low pressure

gp

P

v

gf

P DP

gc

3

Illustration of the Coriolis force. (Left

panel). An observer sitting on the axis of

rotation (North Pole) launches a projectile at

the target. The curved arrow indicates the

direction of rotation of the earth. (Right

panel) The projectile follows a straight-line

trajectory, when viewed by an observer in space,

directed towards the original position of the

target. However, observers and target are

rotating together with the earth, and the target

moves to a new position as the projectile travels

from launch to target. Since observers on earth

are not conscious of the fact that they and the

target are rotating with the planet they see the

projectile initially heading for the target, then

veering to the right. The Coriolis force is a

fictitious force introduced to the equations of

motion for objects on a rotating planet,

sufficient to account for the apparent pull to

the right in the Northern hemisphere or to the

left in the southern hemisphere.

4

The geometry of the earth, showing the distance

from the axis of rotation as a function of the

latitude ? .

r R cos ?(the distance from the axis of

rotation) ? An object on the earths surface at a

high latitude has less angular momentum than an

object on the surface at a low latitude.

v 2?r cos( ? ) / t where t 1 day (86400

seconds). The latitude of Boston is 42? plugging

in numbers, you will find that you are traveling

at a constant speed v 1250 km/h (800 mph!).

1667 km/hr at the equator. Note sound speed

1440 km/hr

5

- Coriolis Force (Northern Hemisphere)

- An air parcel (mass) begins to move from the

Equator toward North Pole along the surface

of the earth. - The parcel moves closer to the axis of

rotation r decreases - The parcels angular velocity is GREATER THAN

the angular velocity of the earths surface at

the higher latitude.

It deflects to the right of its original

trajectory relative to the earths surface. In

the Southern Hemisphere, the parcel would appear

to deflect to the left.

The angular momentum of an object on the earth

due to the planets rotation L mr2 ?. The

requirement that L be conserved implies that, if

r changes, ? must change so as to counteract the

change in r, i.e. ? L/(mr2). For example, if r

were to decrease by factor 2, ? would increase by

factor 4 so that L would stay unchanged. Example

skater "spinning up" note that the skater

really does spin up, by doing work (adding energy

to the spinning motion !

6

The air parcel is deflected to the right.

7

We thus find in all cases that the Coriolis force

is exerted perpendicular to the direction of

motion, to the RIGHT in the Northern Hemisphere

and to the LEFT in the Southern Hemisphere.

Coriolis acceleration F/m 2?v sin( ? ).

Coriolis acceleration increases as ?

(latitude) increases, is zero at the equator.

8

Coriolis acceleration F/m 2?v sin( ? ).

A sample calculation ? 7.5 ? 10-5 s-1 v

10 m/s (36 km/hr, 21.6 mph) l is 42 N

(Boston), sin(l) 0.67 Coriolis acceleration 1

? 10-3 ms-2 The change in velocity is

3.6 m s-1 in 1 hour (3600 s), during which the

parcel travels 36 km in its original

direction. The change in velocity would be 86 m

s-1 in 24 hours if the Coriolis acceleration

stayed the same over the whole period. Obviously

this will not be the case.

9

Deflection of an object by the Coriolis

force. ?y ? (?x)2 / v sin(?) (a) A

snowball traveling 10 m at 20 km/h in Boston

(42N) 20 km/hr 5.5 m/s ? 7.5 ? 10-5 s-1

sin (l).67 Dx10 ?y 9.1 ? 10-4 m (b) A

missile traveling 1000 km at 2000 km/h at 42 N. v

555 m/s, Dx1 ? 106 m ?y 9.05 ? 105 m. At

Boston (? 42?N), we find that a snowball

traveling 10 m at 20 km/h is displaced by ?y 1

mm (negligible), but a missile traveling 1000 km

at 2000 km/h is shifted 100 km (important!). Note

the importance of (?x)2

gc 2 W v sin (l) t Dx/v ? Dy ½ gc t2

10

low pressure

Pressure gradient force

N

high pressure

S

Motion of an air subjected to a north/south

pressure gradient. Pt. A1, initially at rest

Pt. A3, geostrophic flow. The oscillatory motion

depicted in the previous slide is usually not

observed in the real atmosphere, because

atmospheric mass will be redistributed to

establish a pressure force balanced by the

Coriolis force, and motion parallel to the

isobars.

11

- Geostrophy

- For air in motion, not on the equator,

- Coriolis Force ? Pressure gradient force

- Air motion is parallel to isobars

The geostrophic approximation is a simplification

of very complicated atmospheric motions. This

approximation is applied to synoptic scale

systems and circulations, roughly 1000 km. (It is

easiest to think about measuring the pressure

gradient at a constant altitude, although other

definitions are more rigorous. )

12

Circulation of air around regions of high and low

pressures in the Northern Hemisphere. Upper

panel A region of high pressure produces a

pressure force directed away from the high. Air

starting to move in response to this force is

deflected to the right (in the Northern

Hemisphere), giving a clockwise circulation

pattern. Lower panel A region of low pressure

produces a pressure force directed from the

outside towards the low. Air starting to move in

response to this force is also deflected to the

right, rotating counter-clockwise. Directions of

rotation of the wind about high or low centers

are reversed in the Southern Hemisphere, as

explained earlier in this chapter.

13

The effect of friction around a high pressure

region is to slow the wind relative to its

geostrophic velocity. This causes the pressure

force to slightly exceed the Coriolis force. The

three forces add together as shown in the figure.

Air parcels gradually drift from higher to lower

pressure, in the case shown here, from the center

of a high pressure region outward. An analogous

flow (inward) occurs in a low-pressure region.

14

Air converges near the surface in low pressure

centers, due to the modification of geostrophic

flow under the influence of friction. Air

diverges from high pressure centers. At altitude,

the flows are reversed divergence and

convergence are associated with lows and highs

respectively, closing the circulation through

analogous processes noted in the sea breeze

example

15

Near surface circulation around a low pressure

areaMarch 7, 2006.

Jet Stream

16

THE HADLEY CIRCULATION (1735) global sea breeze

- Explains

- Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)

- Wet tropics, dry poles

- General direction of winds, easterly in the

tropics and westerly at higher latitudes - Hadley thought that air parcels would tend to

keep a constant angular velocity. - Meridional transport of air between Equator and

poles results in strong winds in the longitudinal

direction.

17

Reminder of the sea breeze Distribution of

pressure with altitude. The atmosphere expands

as it is heated over the land, generating

buoyancy and increasing the scale height H. The

rate of pressure decline with altitude is

reduced, therefore at altitude, the pressure is

higher over land than over the adjacent sea,

which causes mass to be transferred to the air

column over the sea. Surface pressure over the

ocean is therefore increased, giving rise to the

distribution of pressure shown in the figure.

18

THE HADLEY CIRCULATION (1735) global sea breeze

- Explains

- Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)

- Wet tropics, dry poles

- General direction of winds, easterly in the

tropics and westerly at higher latitudes - Hadley thought that air parcels would tend to

keep a constant angular velocity. - Meridional transport of air between Equator and

poles results in strong winds in the longitudinal

direction. - Problems 1. does not account for Coriolis force

correctly 2. circulation does not extend to the

poles.

19

GLOBAL CLOUD AND PRECIPITATION MAP

(intellicast.com)

11 Oct 2005

Today

Images (3) show colder temperatures as brighter

colors

20

Global Circulation and Precipitation as indicated

by satellite images

11 Oct 2005

18 Feb 2007

- ITCZ location, strength

- Wet and Dry season in Amazônia

- Strength and location of polar and subtropical

jet streams - Images show colder temperatures as brighter colors

21

TROPICAL HADLEY CELL

- Easterly trade winds in the tropics at low

altitudes - Subtropical anticyclones at about 30o latitude

22

Global winds and pressures, July

warm

warm

cold

cold

land

sea

23

CLIMATOLOGICAL SURFACE WINDS AND PRESSURES(July)

24

CLIMATOLOGICAL SURFACE WINDS AND

PRESSURES(January)

25

warm

cold

26

TIME SCALES FOR HORIZONTAL TRANSPORT(TROPOSPHERE)

1-2 months

2 weeks

1-2 months

1 year

27

Buoyancy and Lapse RateThe concept of an air

parcel

1) It's a distinct 'block' of air in an

environment of air we often assume it has

volume of 1 m3. It has to be small enough so

that it has uniform properties (T, P, etc).

Its a fictional entity that helps us to think

through a physical process. 2) We can follow it

(as if it were colored with dye) and it stays

together (the same molecules are inside at the

end of a process as there originally). 3) At the

beginning of any of thought exercise, it has the

same characteristics as its surrounding

environment. 4) The parcel can change with time,

by moving, emitting or absorbing heat radiation,

etc --usually in a way we can

describe with equations. 5) The environment of

the parcel can change too. The parcel changes as

a parcel NOT necessarily with the environment.

28

Buoyancy force Forces on a solid body immersed

in a tank of water. The solid is assumed less

dense than water and to area A (m2 ) on all

sides. P1 is the fluid pressure at level 1, and

P1x is the downward pressure exerted by the

weight of overlying atmosphere, plus fluid

between the top of the tank and level 2, plus the

object. The buoyancy force is P1 P1x (up ?) per

unit area of the submerged block.

D2

P1x

D1

29

The buoyancy force and Archimedes principle.

1. Force on the top of the block P2 ? A r

water D2 A g (A area of top) weight of the

water in the volume above the block 2. Upward

force on the bottom of the block P1 ? A r

water D1 A g 3. Downward force on the bottom of

the block weight of the water in the volume

above block weight of block r water D2 A g

r block (D1 - D2) A g Unbalanced, Upward force

on the block ( 2 3 ) Fb r water D1 A g

r water D2 A r block (D1 - D2) A g r

water g Vblock r block g Vblock (r water r

block) V g

weight of block BUOYANCY

FORCE weight of the water (fluid) displaced by

the block

Volume of the block (D1 D2) A

30

VERTICAL TRANSPORT BUOYANCY

Balance of forces

zDz

Object (r)

Fluid (r)

z

Note Barometric law assumed a neutrally buoyant

atmosphere with T T

T

T would produce bouyant acceleration

31

Vertical transport Pressure, work, and

Temperature

Question Where does the energy come from for an

air parcel to do this work on the atmosphere?

32

Change of atmospheric temperature with altitude (

? pressure ) Atmospheric pressure vs altitude

follows the barometric law, DP-rgDz . Let's

think of an ideal case where the buoyancy forces

and the weight of an air parcel are perfectly

balanced at every altitude, and we neither add or

remove heat as the parcel moves. Because an air

parcel expands as pressure is lowered, it must do

work on the atmosphere as it moves up. The only

source of energy is the motion of the molecules,

and therefore the air parcel must get colder as

it moves up. Two steps are needed to understand

how an air parcel that moves up or down changes

it temperature. Step 1. Figure out the

exchanges of energy between the air parcel and

the environment as the parcel changes its

pressure, using the definition of heat capacity

and Boyle's law. Step 2. Relate this energy

balance to the change in altitude, using the

barometric law.

33

Boyle's Law P1V1 P2V2 How can we use Boyle's

Law to determine the change in V when P changes,

for a parcel of air (at constant temperature)?

Boyles Law P2V2 P1V1 P1DV V1DP DPDV

P1V1 P1DV V1DP, or DP/DV P1/V1

P1V1

V

(P1 DP1)( V1 DV1) P2V2

Boyles law

P

P1DP1 P2 V1 DV1 V2

This is an example of how we can understand the

relationship between two properties of air (or

any gas), when both change together, by dividing

the process into very small steps where one

changes while the other is held constant, then

hold the first constant and change the one

initially held fixed.

?V/V1 - ?P/P1

34

How do we get energy out of molecular

motion Heat capacity or Specific heat of a

substance The specific heat (Cp) of a substance

is defined as the energy needed to raise the

temperature of 1 kg by 1o K (the "p" denotes that

the pressure is held constant). This energy goes

into the thermal motions of the atoms and

molecules (think of a "golf-ball atmosphere").

The specific heat is a quantity we can measure

for any gas. It tells us how much energy we

extract from the motion of the molecules to lower

the temperature of 1 kg by 1o K. The energy

obtained by lowering T is the negative of this

amount Energy that must be added to a parcel

to change T by DT

m cp DT Energy obtained (total) by lowering

T by DT m cp DT. Work done against (or by)

atmospheric pressure to change the pressure of

an air parcel by DP is given by P DV. ( e.g.,

for the cylinder at the right, Work Dh F P A

Dh P DV ) - m cp DT P DV (basic energy

balance)

P

P

Dh

Piston with top area A, volume Ah

h

35

- mcp DT P DV (basic energy balance)

VDP - P DV (Boyles law) gtgt - mcp DT

- VDP DP - g r DZ (Barometric

law) gtgt- mcp DT (Vr) g DZ rV m mass

of parcel We see that for an air parcel moving

vertically in a hydrostatic atmosphere

(barometric law applies), - cp DT

g DZ DT / Dz

-g/cp - 9.8 oK/km

This change in temperature with altitude is

called the "adiabatic lapse rate". cp 1005

J/kg/K g 9.8 m s-2 gtgt - g / cp 9.8 x

10-3 K/m or 9.8 K/km.

36

The change in temperature with altitude in the

atmosphere. The example is from 30 degrees north

latitude in summer.

37

ATMOSPHERIC LAPSE RATE AND STABILITY

Lapse rate -dT/dz

Consider an air parcel at z lifted to zdz and

released. It cools upon lifting (expansion).

Assuming lifting to be adiabatic, the cooling

follows the adiabatic lapse rate G

z

G 9.8 K km-1

stable

z

unstable

- What happens following release depends on the

local lapse rate dTATM/dz - -dTATM/dz gt G e upward buoyancy amplifies

initial perturbation atmosphere is unstable - -dTATM/dz G e zero buoyancy does not alter

perturbation atmosphere is neutral - -dTATM/dz lt G e downward buoyancy relaxes

initial perturbation atmosphere is stable - dTATM/dz gt 0 (inversion) very stable

ATM (observed)

inversion

unstable

T

The stability of the atmosphere against vertical

mixing is solely determined by its lapse rate.

38

EFFECT OF STABILITY ON VERTICAL STRUCTURE

39

WHAT DETERMINES THE LAPSE RATE OF THE ATMOSPHERE?

- An atmosphere left to evolve adiabatically from

an initial state would eventually tend to neutral

conditions (-dT/dz G ) at equilibrium - Solar heating of surface and radiative cooling

from the atmosphere disrupts that equilibrium and

produces an unstable atmosphere

z

z

z

final G

ATM G

ATM

initial

G

T

T

T

Initial equilibrium state - dT/dz G

Solar heating of surface/radiative cooling of

air unstable atmosphere

buoyant motions relax unstable atmosphere back

towards dT/dz G

- Fast vertical mixing in an unstable atmosphere

maintains the lapse rate to G. - Observation of -dT/dz G is sure indicator of

an unstable atmosphere.

40

The change in temperature with altitude in the

atmosphere. The example is from 30 degrees north

latitude in summer.

41

IN CLOUDY AIR PARCEL, HEAT RELEASE FROM H2O

CONDENSATION MODIFIES G

Wet adiabatic lapse rate GW 2-7 K km-1

z

T

RH 100

GW

Latent heat release as H2O condenses

GW 2-7 K km-1

RH gt 100 Cloud forms

G

G 9.8 K km-1

42

Atmospheric temperature and dewpoint for a

typical summer day shows the "planetary boundary

layer" or "atmospheric mixed layer", that

develops as the sun heats the ground in the

daytime. This graph is drawn from actual data

obtained by Harvard's Forest and Atmosphere

Studies group during an experiment (code name

"COBRA") over North Dakota in August, 2000.

43

What you see Puffy little clouds, called fair

weather cumulus, occurring over land on a typical

afternoon. The lapse rate in the mixed layer is

approximately adiabatic, and air parcels heated

near the ground are buoyant. Each little cloud

represents the top of a buoyant plume.

(Photograph courtesy University of Illinois Cloud

Catalog).

44

Moist pseudo-adiabatic lapse rate Air is heated

by release of latent heat when water condenses T

will decline less rapidly than the dry adiabat

Pressure (Mb)

Temperature (C)

-40 0 40

1000 -9.5 -6.4 -3.0

600 4.2km -9.3 -5.4

200 11.8km -8.6

Dry Adb. -9.8 -9.8 -9.8

Ambient T 15 (-gt35) -13 -58

- -g/(cp l Dw/DT )

- l latent heat of vaporization (J/kg)

Dw/DTchange in spec humidity/K

45

(No Transcript)

46

(No Transcript)

47

Photo S. Wofsy, Manaus, Brazil, 1987.

48

VERTICAL PROFILE OF TEMPERATUREMean values for

30oN, March

Radiative cooling (ch.7)

- 3 K km-1

Altitude, km

2 K km-1

Radiative heating O3 hn e O2 O O O2 M e

O3M

heat

Radiative cooling (ch.7)

Latent heat release

- 6.5 K km-1

Surface heating

49

DIURNAL CYCLE OF SURFACE HEATING/COOLINGventilat

ion of urban pollution

z

Subsidence inversion

MIDDAY

1 km

G

Mixing depth

NIGHT

0

MORNING

T

NIGHT

MORNING

AFTERNOON

50

SUBSIDENCE INVERSION

typically 2 km altitude

51

FRONTS

WARM FRONT

WIND

Front boundary inversion

WARM AIR

COLD AIR

COLD FRONT

WIND

WARM AIR

COLD AIR

inversion

52

TYPICAL TIME SCALES FOR VERTICAL MIXING

- Estimate time Dt to travel Dz by turbulent

diffusion

tropopause

(10 km)

10 years

5 km

1 month

1 week

2 km

planetary boundary layer

1 day

0 km