Basic Assumptions of Evolutionary Theory

1 / 160

Title:

Basic Assumptions of Evolutionary Theory

Description:

... separated from that of chimpanzees and bonobos, our closest primate relatives. ... adaptations or traits distinguish humans form their nearest primate relatives? ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:72

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Basic Assumptions of Evolutionary Theory

1

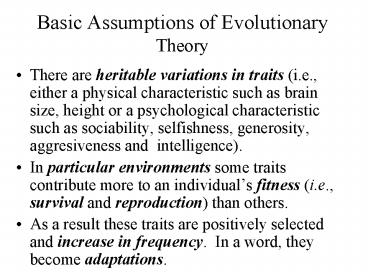

Basic Assumptions of Evolutionary Theory

- There are heritable variations in traits (i.e.,

either a physical characteristic such as brain

size, height or a psychological characteristic

such as sociability, selfishness, generosity,

aggresiveness and intelligence). - In particular environments some traits contribute

more to an individuals fitness (i.e., survival

and reproduction) than others. - As a result these traits are positively selected

and increase in frequency. In a word, they

become adaptations.

2

Basic Assumptions of Evolutionary Psychology

- Human thought, feeling and action reflect

adaptations or traits that evolved over the past

5,000,000 years when the human line separated

from that of chimpanzees and bonobos, our closest

primate relatives. - Adaptations are modular (e.g., vision, language).

But to what extent? How distinct an entity

(e.g., lungs vs jealousy vs sociality)? - Sociality (i.e., group living), is a key human

adaptation. - The costs and benefits associated with our

peculiarly extensive and complex networks of

social relations are the primary source of

selection pressures on humans.

3

Humans Compared to Chimpanzees and Bonobos

- What adaptations or traits distinguish humans

form their nearest primate relatives? What do

these adaptations imply about human social

psychology? - Large brains

- Long periods of juvenile dependence

- Extensive parental care including the transfer of

vast amounts of information - Multigenerational bilateral kin networks

4

(And thats not all! Theres )

- Habitual bipedal locomotion

- Cryptic or concealed ovulation

- Menopause

- Culture, including language

- Letal competition among kin-based coaltions

- N.B. A few other species exhibit some of these

adaptations. However, only humans possess the

entire set of them in their most complex form.

5

The Adaptive Value of a Trait Depends on Its

Contribution to Fitness

- The ultimate and most direct measure of fitness

is the number of healthy offspring or

reproductive success (RS). Thus, a traits

benefits refers to how much it increases RS and

its costs, how much it decreases RS. - We often use less direct or more proximal

measures of fitness that we assume contribute to

RS (e.g., as health, strength, wealth) for

convenience.

6

Why Do We Think Group Living Is an Adaptation?

- Because it is universal.

- Because it is typical of species most closely

related by common descent to humans. - Because it has neurophysiological correlates

(e.g., neocortex ratio and social network

density ostracism and activation of pain area

in brain). - Because it has affective correlates (e.g.,

isolation and ostracism are painful and universal

punishments while being liked and respected are

pleasurable and universal rewards). - Beause it has cognitive correlates (e.g., Theory

of Mind cheater-detection modules). - Because bio-economic analyses of fitness (i.e.,

benefits to RS relative to it costs) suggests

living in groups is adaptive.

7

Do species most closely related to humans

(chimps and bonobo) live in groups? Yes. Are

chimp groups and bonobo groups similar? No. So

what?

8

Are there neurophysiological correlates of group

living? Yes. Neocortex size increases with

group size social complexity.

9

Bio-economic Analysis

- In examining sociality as an adaptive strategy

Richard Alexander considers the recurrent

problems faced by groups in the ancestral

environment and compares the hypothetical fitness

costs and benefits of increasing group size

from living with several conspecifics (e.g., in

separate nuclear families), through a few dozen

(e.g., nuclear family coalitions or extended

families), one or two hunderd (hunter-gatherer

groups), to thousands or millions (towns, cities,

clans, tribes and nations).

10

The cost/benefit return of increasing groups

size Minimizing home, den or nest site shortages

as an adaptive problem

11

The cost/benefit return of increasing group size

Minimizing disease as an adaptive problem

12

The cost/benefit return of increasing group size

Minimizing food shortages (when food is widely

distributed, thus, readily found) as an adaptive

problem

13

The cost/benefit return of increasing group size

Minimizing food shortages when food sites are few

and hard to find as an adaptive problem

14

The cost/benefit return of increasing group size

Minimizing food shortages when food is large,

hard to catch animals (prey) as an adaptive

problem

15

The cost/benefit return of increasing group size

Minimizing the danger of predation

16

- Protection from predation provides the largest

benefit to fitness from living in groups during

most of human evolution. - However, humans have achieve ecological dominance

so that weve not had to fear predation by other

species for the past 15-20,000 years. Even

before then, predation by other species was

minimized at a relatively small group size

compared to the size of human clans, tribes and

nations. - 3. So why do we live in such large groups?!

17

If humans are not the prey of other species, do

they still suffer predation?

- Yes, of course! We are our own prey! Predation

by other human groups is likely to have been a

big adaptive problem for our species!! - (N.B. Our overlooking this suggest how the

ecological dominence of modern humans biases our

thinking about the ancestral environment?)

18

- For many thousands of years the most

significant predator on group living humans has

been other group living humans. To explain how

this could cause humans live in very large

groups, Alexander proposed the balance of power

model

19

The Balance of Power Model

- i. In multi-group environments, the members

felt vulnerability is inversely related to the

relative size of their group. - Felt vulnerability motivates smaller groups to

form coalitions whose size counter-balances or

excedes that of the previously largest group. - As a result, felt vulnerability decreases among

members of the newly formed coalition (and

increases among members of the previously largest

group). - This in turn motivates the latter also to seek

coalition partners which, if successful, motives

the former to seek further coalition partners

etc. Thus, group size spirals upward to some

limit where there is a balance of power that

minimizes feelings of vulnerability and

additional coalitions are too costly or

unavailable.

20

Living inKin Groups is Easier to Explain Than

Living in Non-Kin Groups

- The protection function of groups implies

altruism Group members willingly incur large

costs to benefit others (e.g., some will risk

death to protect fellow members from an animal

predator or a raiding group). - Until the second half of the last century the

fact of altruism, was a puzzle. How could such

tendencies evolve if they cause harm to the actor

and should be selected against? In 1964 Hamilton

showed how in his analysis of inclusive fitness

(kin selection).

21

A Heuristic for Thinking about Hamiltons Theory

- Imagine you are a gene that contributes to the

trait of intelligence. You know that - An individual is your vehicle carries you

through life. - Intelligence contributes to fitness (increases

RS). - The probability that copies of you exist in

relatives of your vehicle increases with their

degree of relatedness to your vehicle. - Then answer the following question

- What what strategy would you want your vehicle

to follow if your goal is insure that copies of

you continue to exist in future generations?

22

Hamiltons Inequality Solves Two Related

Problems Why Living in Kin Groups is Adaptive

and How Altrusim Can be Positively Selected

23

(No Transcript)

24

(No Transcript)

25

(No Transcript)

26

(No Transcript)

27

(No Transcript)

28

(No Transcript)

29

Risky Decisions Involving a Large Non-Kin Group,

a Small Non-Kin Group, or My Family

- The next study indicates that when making a risky

decision for a group, the size of the group and

our ties to its members can cause us to behave

seemily irrationally, i.e., compute costs and

benefits in sub-optimal fashion. - In what sense are such behaviors irrational?

- According to behavioral decision theory or

inclusive fitness theory or both? - Does this consider that adaptations are designed

for recurrent problems, not rare events.

30

Framing of Choices in the Tversky and Kahneman

(1981) Decision Task

- The decision task

- Imagine that Lodz is preparing for the outbreak

of an unusual disease which is expected to kill

600 people. - Two alternative programs to combat the disease

have been proposed. - Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the

consequences of the programs are as follows

31

Positive framing of the Decision Task

- The Certain outcome. If program A is adopted 200

people will be saved. - The Uncertain outcome. If program B is adopted,

there is a one-third probability that 600 people

will be save and a two-third probability that no

people will be saved.

32

Negative framing of the Decision Task

- Certain outcome. If program C is adopted, 400

people will die. - Uncertain outcome. If program D is adopted,

there is a one-third probability that nobody will

die and a two-third probability that 600 people

will die.

33

Tversky and Kahnemans results

- Under positive framing of the decision people are

risk averse - 72 of their respondents chose the certain

outcome. - 28 of them chose the uncertain or probabilistic

outcome.

34

Tversky and Kahnemans results

- Under negative framing people are risk prone

- 22 chose the certain outcome.

- 78 chose the probabilistic or uncertain outcome.

35

Peculiar Parameters of theTversky-Kahneman

Decision Task (Wang, 1996 2002)

- The Group is Large and Its Members Have No Ties

to the Respondent. - What Do You Think Would Happen If the Group is

Small and the Decision Makers Ties to the Group

Are Strong?

36

Risk Proneness Decreases with Group Size and

Kinship

37

Risk Aversion is Sensitive to Survival Rates for

Non-Kin Groups But Not for Kin Groups (Choices

are Positively Framed)

38

Decisions about Kin Groups Violate Rational

Choice Preferences Under Positive Framing for

Probabilistic Outcomes When Its Expected Value is

Less than that of the Certain Outcome

Choice Percentage

Non-kin

Kin

Proportion of Group Saved for Certain

(Note In all conditions the probalistic outcome

is 1/3rd chance of saving all group members)

39

Members of Kin Groups Are Nice to Each Other

But Not Under All Conditions

- Parental investment hypothesis (derived from

inclusive fitness theory) argues parents should

incur a cost to benefit a child when it

contributes to parents inclusive fitness more

than doing something else with their resources.

If so, what should be predicted (think of the

earlier heuristic) - 1. When parents decide on investing in a male

versus a female offspring? - 2. When parents are rich versus when they are

poor? - 3. When they are step-parents?

40

Recall Hamiltons Inequality

- Note that it says under certain conditions

altruism toward kin may actually decrease

inclusive fitness. This happens when - r 0 and/or C gt r B

- As relatedness (r) between donor and recipient

decreases and the cost of altruism (C) increases

the donor should act in an increasingly

unaltruistic manner. The next slides summarizes

research (Wilson Daly, 1998) comparing the

likelihood of child abuse and child homocide,

decidedly unaltruistic acts, in families with two

biological parents and families with one

stepparent (typically the father). It

emphatically supports Hamiltons prediction.

41

(No Transcript)

42

(No Transcript)

43

(No Transcript)

44

However a Violent Father or Brother Did Have

Benefits

- When a relative was murdered, Vikings had the

choice between a revenge murder or accepting

blood money. Berserkers were individuals with a

reputation of being extremely fierce and

dangerous. If a murderer was a berserker (or his

father or brother), the aggrieved relatives of

the victim were significantly more likely to

accept blood money, but to prefer a revenge

killing if the murderer was not a berserker or a

close relative. - In the next slide the plotted variable is the

ratio of observed murders relative to the number

expected on the basis of the proportion of

berserkers or non-berserkers in the population.

Source 34 murders recorded in Njal's Saga.

45

(No Transcript)

46

Viking berserkers suffered significantly higher

rates of mortality at the hands of their own

community but their behavior benefitted male

members of their families. Therefore,

Berserkers were altruists, yes? (Families of the

three berserkers in the Icelandic Njals Saga

suffered significantly less mortality than the 7

families that did not contain a recognized

berserker.)

120 100 80 60 40 20 01

47

Something to Think About

- From the 8th through the 10th century, the

Vikings were the fiercest and most feared group

in Europe, raiding and plundering settlements on

the northern and western coasts of the continent

as well as the interior of eastern Europe. - A dozen centuries later their descendents are the

most peaceful and least feared group in Europe.

48

- In light of Hamiltons theory, how could

cooperation among non-kin evolve?

49

Non-kin Altruism, Cooperation and Equity Some

Questions for Later

- 1. Have the benefits of cooperation

sufficiently outweighed its costs (transaction

costs and opportunity costs) to create selection

pressures on human psychology? - 2. Can large cooperative networks (e.g.,

markets, trading networks) function without

cognitive adaptations that allow participants to

calculate the risks of a transaction?

50

- 3. Are there indirect benefits of non-kin

altruism (e.g., giving money to charity to poor

strangers)? - 4. Are costly acts with no return benefit

(e.g., altruistic punishment in a one-shot

prisoners dilemma game) more a matter of

satisfying a need for equity or fairness than

true altruism? Or a need for vegence? If so,

how would such motives be positively selected?

51

Skinnerians and others of their ilk say

Altruism need not assume the operation of

cognitive adaptations like cheater-detection,

empathy or Theory of Mind

- A radical behaviorist demonstrates that helping a

stranger develops and is maintained because it

the act of helping is reinforced by its

consequences. - Hence assumptions about cognitve adaptations are

theoretically unnecessary, a violation of

scientific parsimony.

52

- In the following experiment subjects are free to

press a button as quickly as they want to record

the end of a trial. In two conditions this also

turns off a noxious noise piped into a strangers

ears i on every trial (continuous

reinforcment), ii on some randomly selected

trials (partial reinforcement), or iii on none

of the trials (control), where the noise ends

automatically after a fixed interval. The desire

or effort to help is indicated by how quickly the

subject presses the button. - N.B. The stranger is a confederate of the

experimenter and there is no actual noise being

piped into his ears.

53

(No Transcript)

54

A Question to Ponder

- If humans do persist in helping strangers and if

they do so because the act is intrinsically

reinforcing, where does that leave theories that

assumes complex computations of costs and

benefits plus discounting (e.g., for age, health,

relatedness, etc.) are necessary for the

evolution of such behavior?

55

THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN BEHAVIORISTS AND

COGNITIONISTS CONTINUES IS COOPERATION MINDLESS

OR DO YOU NEED COGNITIVE ADAPTATIONS?

- Sidowski Cooperation in essentially

coordinating interpersonal behavior and can be

achieved when individuals are totally unaware

they are interacting with another person. Just

assume the Law of Effect or Win-Stay,

Lose-Change and forget about complex

computations. - Kelly Not true. You need to think, to take the

others perspective and think about what they are

thinking to achieve cooperation. Let me show

you..

56

The Sidowski-Kelley Coordination Game

57

The results of applying the Win-Stay-Lose-Change

rule when both players, P and O, respond

simultaneously. Note that there are only three

combination of button-press choices possible on

the first trial and from then on the

Win-Stay-Lose-Change rule determines each

players outcomes

58

The Three Starting Combinations

- a. P chooses the right button and O the left.

As a result both receive positive outcomes. - b. Both P and O choose the left button. As a

result P receives a positive outcome and O a

negative outcome. (N.B. The case in which both

choose the right button is isomorphic with this

one.) - c. P chooses the left button and O the right.

As a result both receive negative outcomes.

59

Win-Stay, Lose-Change Wins An Ambiguous Triumph

for Radical Behavior Theory

60

- According the Win-Stay-Lose-Change rule,

cooperation (mutual reward) is inevitable under

conditions of simultaneous responding which turns

out to be the case whether or not P believes O is

another person or a computer. - But see what happens when one simple parameter is

changed, i.e., P and O respond in alternation

rather than simultaneously. Suppose O responds

first and P second. The three starting trials

are as follows (continuing to apply the

Win-Stay-Lose-Change rule as before)

61

Win-Stay Doesnt Win An Unambiguous Triumph for

Social Cognition

62

- Unless they start out cooperating (a mutually

rewarding exchange), they should never achieve

cooperation according to the Win-Stay-Lose-Change

rule. - But they do achieve cooperation if P knows O is

another person (not, say, a computer). How is

this possible? Well, not by using Skinnerian

reinforcement theory which is inadequate to

explain this effect. We have to go elsewhere

for an explanation. Where? What assumption do

we need to make beyond those of reinforcement

theory to explain how cooperation is possible in

a mutual-fate-control sitution when we know our

outcome depends on another person, a stranger,

and his or her outcome on us?

63

- New Assumptions TOM, Foresight and Planning

Cooperative Thinking - To achieve cooperation under these conditions we

foresee having to adjust our strategies and

actions with those of others so as to reconcile

potential conflicts of interests with maximum

benefit or least cost. To do so we represent in

our mind, as best we can,what others intend to do

(their plan or strategy), and what they think we

intend to do (our plan or strategy). - Why?

- In order to decide whether others are

trustworthy. - In order to anticipate and, thus, coordinate each

othersactions, thereby achieving a mutually

beneficial or least costly relationship (e.g.,

reciprocity or division of labor).

64

- The most common experimental paradigms for

observing cooperative thinking is the two-person

prisoners dilemma game (PDG) and the n-person

prisoners dilemma game (SDG).

65

The Classic PDG

66

The Social Dilemma Game (SDG)

- The SDG is an n-person (n gt 2) PDG. Say, as the

next Table assumes at least 5 out of a group of 7

members have to contribute their endowment a

sum of 5 given them at the beginning of the

experiment to fund a public good. The latter

means that all members will benefit by receiving

10 whether or not they incurred the cost of the

public good, i.e., whether they were a

contributor or a non-contributor. So like all

public goods, all members, contributor and

non-contributors benefit if the group meets the

cost criterion. Do you see why this creates a

conflict of interest similar to that in the PDG?

67

- As in the PDG the largest benefit or payoff goes

to defectors (i.e., non-contributors) if there

are enough cooperators (i.e., contributors) to

provide the public good. - The next largest goes to the cooperators if

enough others cooperate to provide the public

good. - The next largest goes to defectors if there are

not enough cooperators to provide the public

good. - And least benefit, the suckers payoff goes to

cooperators when there are too few to provid the

public good.

68

- Next we lay out the conditions that define the

standard SDG - It is a non-iterated (one-shot) game.

- Members are strangers.

- Their decisions are completely anonymous.

- There is no contact or discussion prior to,

during or after the decisions. They arrive and

leave the experiment never have seen any member

of their group.

69

- Non-standard versions devised to compare with the

standard SDG - Money-back is a norm imposed on the group that

guarantees cooperators will get their money back

if there are two few of them to provide the

public good, ergo, no one gets a suckers payoff

and looses his endowment. - No free-riders is a norm imposed on the group

that guarantees defectors will not benefit more

than cooperators if the public good is provided,

ergo, there is no temptation to defect.

70

The standard SDG and variations in Caporeal,

Dawes, Orbell and van de Kragt (1989)

Cooperation requires a minimum number of members

to contribute.

71

- Some SDG studies also vary

- Whether or not individuals have a brief

discussion prior to deciding anonymously. - Whether or not the experimenter designated who

was to contribute (but they could still defect

because their decision is anonymous). - Whether or not everybody had to contribute

(called super simple because members did not

have to decide about cooperating but again anyone

could still defect since their decision is

anonymous).

72

Rates of Public Goods Provision

73

Rates of Contribution when External Authority

Designates the Anonymous Contributors

74

Intergroup Cooperation Is Distrust of the Other

the Default for Outgroups (Even Minimal

Outgroups)?

75

Reciprocity Knowing and Providing What is Due

Another Uncompelled Equity and Fairness

- 1. Will a person abide by a contract when it

is costly to do so and the person cannot be

punished for defecting? - 2. Will a person punish defectors when it is

costly to do so and it cannot force them to

cooperate? - 3. Will a person expect to receive punishment

as a result of defecting when punishment is

costly to adminsiter and it cannot benefit the

punisher (by compelling cooperation)? - If you say yes to any or all of these

propositions what does it imply about equity and

fairness as an adaptation?

76

Employees Contracted and Delivered Effort in

One-Shot (non-repeated) Employer-Employee

Gain (see Gintis, et al., 2003)

Employees Average Effort

Payoff Offer to Employee by Employer

77

The Mystery of Altruistic Punishment

- Cooperation can be maintain by punishing

free-riders. - Humans seem designed to punish non-cooperators in

that they do so even when it is costly and there

is no direct return benefit (e.g., in a one-shot

exchange). - If punishment of free-riding is costly and cannot

elicit return benefits from the free-rider, how

can it be postively selected and become an

adaptation? iveEven when it is costly to them and

they do not directly benefit as a result (e.g.,

in a one-shot game)?

78

Contributions in a repeated public goods game

with the same partner or a new partner (stranger)

under conditions of punishment and non-punishment

(see Gintis, et al., 2003)

Punishment option Removed

Punishment Permitted

Average Contribution

Games

79

- Milgrams study of obediance is the best known

study with data about what people expect someone

to do when punishing another person. At first

glance, the findings seem to argue against

assuming the tendency to punish free-riders is an

adaptation. - But does it? Is the person being punished

free-riding? If not, does the finding imply

anything about tendencies to punish in the

absence of free-riding? Let look at Milgrims

data.

80

Punishing Members Who Refuse to Punish Deviants

May Be Unnecessary to Produce Conformity

Predictions that People (including Self) Will

Refuse to Punish Deviant Learner Are Wrong.

81

(No Transcript)

82

Cooperation and the Division of Labor

- The division of labor is probably the most common

form of cooperation in everyday life. - It is occurs when (i) members know, prefer to or

can do different things and (ii) coordinate their

respective knowledge or performances to their

mutual benefit. - The division of labor can be not only formal,

explicit and hierarchical (e.g., military units,

sports teams, surgical teams, business teams,

etc.) but also informal, implicit and egalitarian

(e.g., families, friends, co-workers and lovers).

83

Cooperation Depends on Trust

- Contrary to Axelrod, simulation studies

demonstrate that his best game strategy,

TIT-FOR-TAT, really isnt. Actually, it counts

for little in respect to inclusive fitness

compared to the partner-selection strategy, i.e.,

being able to distinguish between trustworthy and

untrustworthy partners ahead of time. - If so, then humans, being so eminently

cooperative and cooperation being so vulneralbe

to cheating, must be designed to detect potential

cheaters somehow. You agree, of course? Well

okay, what do we know about such mechanism?

84

The DOG Partner Selection Algorithm

- The secret to DOGs success

- 1 Unlike the other partner selection

strategies, when it assesses the trustworthiness

of a potential partner DOG ignores transaction

costs it doesnt care whether a player

cooperated or defected in prior transactions. - ii Instead it focuses only on opportunity

costs it tries to select the player offering the

highest potential return and never selects a

player one offering a negative return regardless

of whether the player previously defected or

cooperated.

85

- How does DOG work?

- 1. On the first trial DOG assigns a random

preference rank to all other players. - 2. From the second trial on, DOG assigns a

preference rank to all the other players

according to the following X-value rule - a. For any player DOG has ever played in the

past, the X-value is the score DOG earned in the

most recent transaction with that player (X can

vary from some positive value to some negative

value, i.e., it can reflect a large, moderate or

small positive or negative return from the

transaction). - b. In the case of a stranger, a player with

whom DOG has never played, X is the average of

the positive X-values of the players with whom

DOG has played in the past. - 3. On each trial DOG first selects the player

with the largest X-value. - 4. If that player doesnt select DOG as a

partner within three matching rounds, DOG selects

the player with the second largest X-value. - 5. This process continues until all the players

with positive X-values are exhausted at which

point DOG returns to the player with largest

X-value that is still available and repeats the

whole process, ad infinitum.

86

Evidence for mechanism to assess the likelihood

of defecting, cheating, free-riding and

untrustworthiness

87

(No Transcript)

88

Abstract Rule Example

- Rule If you are in category X you have to be

taller than 6.0 feet. Is the rule being

violated? - Card P Someone who is in category X.

- Card not-P Someone who is in category Y.

- Card Q Someone who is 6.5 feet.

- Card not-Q Someone who is 5.5 feet.

89

Social Norm Example

- Norm If you are drinking alcohol you have to be

21 or older. Is it being violated? - Card P Someone is drinking a beer.

- Card not-P Someone is drinking a coke.

- Card Q Someone is 23 years old.

- Card not-Q Someone is 17 years old.

90

What Makes Us More Trustworthy?

- H.L. Menken (Its) the little voice inside

of you that says someone is watching. Which

implies concern about - 1. Being monitored.

- 2. Reputation.

- 3. Opportunity costs (i.e., other members

reject you as a partner in transactions involving

trust). - 4. Other kinds of punishment (e.g., make

him an offer he cant refuse ).

91

Concern about being monitored can implicit and

automatic in transactions involving trust

Computer Monitor (Haley Fessler, 2005)

92

Probability of Allocation Funds to an Agent to

Invest in the Trust Game

Effects of Eyes and Crowd-Noise on Allocation

N 24

N 24

N 29

N 22

N 25

(Haley Fessler, 2005)

93

Cues to Trust and Distrust

- Aside from Cosmides cheater-detection mechanism

she demonstrated using the Wason Selection task,

are there other situational or internal cues

besides reputation, payoff structure (e.g.,

temptations to defect in PDG) and transparency of

return (e.g., rice versus rubber markets) that

are used to compute or infer trustworthiness? - 1. Self-resemblance Facial self-morphing

(conscious and unconscious effects). - 2. Facial prototypes Defector recognition

(specific features, e.g., eye shape?). - 3. How you feel (mood) Oxytocin inhalation.

- 4. Brain activity Anticipation of returns.

94

Whom Do You Trust? Self Resemblance Studies

Using Facial Morphs

95

Plt.08

Plt.01

Plt.001

NS

Plt.01

Experimental Control

Experiment 1

Experiment 2

Experiment 3

Experiment 4

96

Effects of Qxytocin on Investor Transfers with

Human (Trust) and Programmed (Risk)

Trustee (Kosfeld, Heinrichs, Zak, Fischbacher,

Fehr, 2005)

97

Neural Correlates of Reputation Building in

Trustee Brain (King-Casas, Tomlin, Anew, Camerer,

Quartz, Montague, 2005)

98

Human Adaptations for Cheater Detection

Information Processing and Computation Under

Focused and Unfocused Distrust

- In many situations we know who may be tempted to

deceive us. Sometimes, however, we do not. - Focused distrust refers to occasions when we

suspect deception and know the source. - Unfocused distrust refers to occasions when we

suspect deception without being aware of its

source something just doesnt seem right. - Have we evolved to process information under

these two conditions differently compared to when

we trust others?

99

Cheater-detection makes us think more

- If we elaborate on and analyze a lot what

suspected cheaters say, then we should confuse

what their actual statements with inferences we

made while encoding them. - Examples of types of inferences

- Direct inference Her boss says Mary works

quickly and doesnt make mistakes and we infer

Mary is an efficient worker. - Compound inference Her boss says Mary works

quickly etc., and we give a bonus to our most

efficient workers. We infer Mary won a bonus.

100

(No Transcript)

101

(No Transcript)

102

Favorable

Neutral

Favorable ? Unfavorable

Unfavorable ? Favorable

Unfavorable

103

(No Transcript)

104

Suspicion Can Influence Judgment Unconsciously

- In recent experiments a few seconds before they

make a judgment, individuals are subliminally

primed with a word (e.g., an adjective or noun)

presented imbedded in a supraliminal honest or

dishonest face. - The word prime as well as the face is irrelevant

to the judgments they are about to make (e.g., Is

a second word, presented above threshold, an

adjective or a noun?).

105

- The model tested in these experiments assumes

they will elaborate congruent associates to the

subliminal word prime in the honest-face context

and incongruent associates to the subliminal word

prime in the dishonest-face context. - If so, the model predicts that

- when the prime and the to-be judged word are

both nouns or both adjectives, then in the

honest-face context individuals will elaborate

congruent associates to the prime (e.g., the

concept of noun or specific nouns when both the

prime and the supraliminal word are nouns) and

categorization of the to-be-judged word is

facilitated (e.g., faster) whereas in the

dishonest-face context they elaborates

incongruent associates (e.g., the concept of

adjective or specific adjectives when both words

are nouns) and categorization is disrupted (e.g.,

slower). - by the same logic, when the to-be-judged word is

incongruent with the prime (e.g., one is a noun,

the other an adjective), judgments will be

disrupted (e.g., slower) in the honest-face

context and facilitated in the dishonest-face

context.

106

(No Transcript)

107

(No Transcript)

108

(No Transcript)

109

(No Transcript)

110

(No Transcript)

111

Being able to efficiently process information

about our relations with others (e.g., Is he or

she a friend or foe? Is his or her status higher

or lower than mine?) is useful. Is there

evidence that humans are designed to make and

store such computations?

112

Adaptations Mechanisms for Coding Social

Relations

- If humans are designed to live in groups, then

they are also likely to be designed to code

(i.e., recognize, interpret, remember and

elaborate upon) information that reduces the

costs of group living and increase its benefits. - Among the most adaptive pieces of information

concern relations among group members - Who in the group have common interests, are

friends, who have conflicting interests, are

enemies? - Who is has high status (i.e., is powerful, rich,

skillful, etc.), who has low status (i.e., is

weak, poor, inept, etc.)?

113

(No Transcript)

114

(No Transcript)

115

(No Transcript)

116

(No Transcript)

117

(No Transcript)

118

A Procedure for Assessing Cognitive

Categorization of Individuals Are They Perceived

as Belonging Together, Forming a Coalition or

Unit?

119

Suppose You Wanted to Know If Observers Grouped

People Based on Common Interest or Opinion.

- Tell observers about some characteristic of the

people (e.g., sex, age, race, clothes, and what

they said that indicated whether they were pro

or con regarding an issue). - Next ask observers to recall if an individual

made a particular statement (e.g., whether he or

she said X). - Count how often the individual is confused with

another (e.g., observers say he or she made the

statement when it was actually made by another).

120

- What was the reason for these confusions? Did

they occur most often if the two individuals were

the same sex, the same age, the same race, wore

the same t-shirt or had the same opinion (both

were either pro or con)? - Intra-category confusion are most frequent.

Therefore, if confusion occurred most often

between those with the same opinion (both were

pro or both con), then its evidence that

observers were categorizing or cognitively

grouping the individuals based on common opinions

or common interests. Kurzban calls this

coalitional thinking. In Heider, the

grouping would reflect a positive unit

relationship and, perhaps implicitly, a

positive sentiment relationship.

121

(No Transcript)

122

(No Transcript)

123

Social Dominance Orientation Following Ethnic

Prime (Questions on Ashkenazi-Sephardi Relations)

or National Prime (Questions on

Israeli-Palestinian Relations)

124

(No Transcript)

125

Consensus and Conformity

- Intentional cooperation typically is a form of

collective action (e.g., several friends decide

to form a study group, a community decides to

subsidize medical care for the poor a

hunter-gatherer tribe decide to migrate a

country decides to go to war) based on consensus. - An effective consensus must prevent cheating and

free-riding. - This implies social psychological mechanisms to

minimize distrust and insure conformity. - i. Informational influence (e.g., Sherif)

- social comparison

- persuasive argumentation

- ii. Normative influence (e.g., Asch)

- extrinsic reward or punishment

126

But first, the mystery of compliance and human

nature

- What conclusion do you draw about human nature

from the amazing (okay, amazing only to the

naïve) relationship between (i) predicted and

actual compliance and (ii) proximity of victim

to punisher and the amount of pain the latter

is willing to inflict on the former? - Is there other evidence (e.g., studies of

soldiers ordered to shoot someone)? - Implications for normative influence and

conformity and second order punishment?

127

(No Transcript)

128

(No Transcript)

129

(No Transcript)

130

(No Transcript)

131

(No Transcript)

132

The Benefits and Cost of Conformity

- You dont have to learn what to believe or how to

do something. Just imitate others actions and

conform to their beliefs. - Social comparison as an adaptive mechanism for

imitation and conformity. - But imitation and conformity may have opportunity

costs, i.e., you will not discover that there are

better ways of doing something or that there are

more valid views of the world. - Hence, humans may be designed to discount the

validity of others actions or beliefs to the

extent that these actions and beliefs are

themselves products of conformity (not

independently arrived at) and are not objectively

demonstrable. - Is this why conformity in Asch-like normative

influence settings doesnt increase when

unanimous majority becomes relatively large?

133

Why Normative Influence Peaks at a Very Small

Unanimous Majority

- 1. Discounting mechanisms

- i. Majority has shared interests different

from that of deviant. - ii. Non-independence of majority members.

- 2. Futile search for independent evidence or

objective demonstration of the majority choice. - Search is typically done under time stress and at

the cost of cognitive inconsistency (i.e., the

majority seems incorrect) relative to the cost of

social rejection.

134

Conformity to a Unanimous Blame-the-Mother-Not-th

e-Manufacturer Majority in a One Six Member

Group, Two Three Member Groups and Three Two

Member Groups

10K 9K 8K 7K 6K 5K 4K

Degree of Blame

135

Conformity to a Unanimous Blame-the-Mother-Not-th

e-Manufacturer Majority in Groups and in

Non-Groups (Aggregates of Individuals) of

Identical Sizes

Degree of Blame

136

(No Transcript)

137

(No Transcript)

138

- According to Mueller and Mazur (1997), we

automatically judge someons status or dominence

from his or her face (Mueller and Mazur, 1997). - The faces used by Mueller and Mazur are from a

yearbook published by West Point, the U.S.

Military Academy, that trains career army

officers. Some examples (Can you detect

differences in facial dominance?)

139

(No Transcript)

140

- See slides based on WHO data for male-female

differences in mortality as a function of status

competition.

141

Mating

- What does sexual selection theory predict about

male-female difference in - 1. Preferred number of partners?

- 2. Probability of consenting to intercourse?

- 3. Preferred age difference in mate?

- 4. Importance of mates provisioning prospects?

- 5. Importance of mates attractiveness?

142

(No Transcript)

143

(No Transcript)

144

(No Transcript)

145

(No Transcript)

146

(No Transcript)

147

Male-Female Differences in Antecedents and

Consequences of Homicide Demographic Evidence

- How (if at all) might theories of sex differences

in mating strategies, especially their

implications regarding competition between and

within the sexes, explain the differences in the

following data sets?

148

Risky Competition Age- and sex-specific homicide

rates in Canada, 1974-1983.

Female victims

Homicides per million persons per annum

Age (years)

Female offenders

Age (years)

149

(No Transcript)

150

Age- and Sex-specific Rates of Homicide in

Detroit, 1972. (From Wilson Daly, 1985)

Male victims

Homicides per million persons per annum

0-4 10-14 20-24 30-34

40-44 50-54 60-64

70-74 80-84 85 5-9

15-19 25-29 35-39

45-49 55-59 65-69 75-79

Age (years)

Male offenders

0-4 10-14 20-24 30-34

40-44 50-54 60-64

70-74 80-84 85 5-9

15-19 25-29 35-39

45-49 55-59 65-69 75-79

Age (years)

151

Age- and Sex-specific Rates of Homicide in

Detroit, 1972. (From Wilson Daly, 1985)

Female victims

0-4 10-14 20-24 30-34

40-44 50-54 60-64

70-74 80-84 85 5-9

15-19 25-29 35-39

45-49 55-59 65-69 75-79

Homicides per million persons per annum

Age (years)

Female offenders

0-4 10-14 20-24 30-34

40-44 50-54 60-64

70-74 80-84 85 5-9

15-19 25-29 35-39

45-49 55-59 65-69 75-79

Age (years)

152

(No Transcript)

153

Unemployment Rates Among Male Homicide Offenders,

Male victims, and the Male Population-at-Large in

Detroit, 1972. (From Wilson Daly, 1985)

154

Proportions Unmarried Among Male Homicide

Offenders, Male victims, and the Male

Population-at-Large in Detroit, 1972. (From

Wilson Daly, 1985)

155

Spousal Homicde Rates as a Function of the Age

Difference Between Wife and Husband. Canada,

1974-1983.

Wife older

Wife younger

156

Motive Categories and the Number of Cases

(Victims) Within Each, for 588 Criminal Homicides

in the City of Philadelphia, 1948-1952. (From

Wolfgang, 1958)

157

Two hundred Twelve Closed Social Conflict

homicides in Detroit, 1972, in Which Victim and

Offender Were Unrelated (Friends, Acquaintances

or Strangers), Classified by Conflict Typology

and by the Sexes of the Principals. (From

Wilson and Daly, 1985)

158

Dispositions of Spousal Homicides in Various

Studies. (Data from Canada and Detroit are from

Daly Wilson, 1988 for Miami from Wilbanks,

1984 and for Houston from Lundsgaarde, 1977)

159

The Probability of Suicide After Homicide, in

Relation to the Sexes of Killer and Victim, and

Their Relationship, Canada, 1974-1983

160

Intergroup Relations

- 1. Realistic Group Conflict Theory (Sherif)

versus Social Categorization Theory (Tajfel)

Are they incompatible? - 2. The minimal intergroup situation Is

advantaging the ingroup (or disadvantaging

outgroups) the default reaction to social

categorization? Is strategy likely to have been

adaptive (positively selected for) in the

ancestral environment - 3. What about N-group (not merely one in-group

and one outgroup) environments and coalitions as

in the balance-of-power model? - 4. Group/category membership, the hierarchy of

groups/categories, and self-evaluation Are

there dimensions other than prestige or power for

ordering groups?