Writing Across Communities Literacy and Diversity at UNM - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 17

Title:

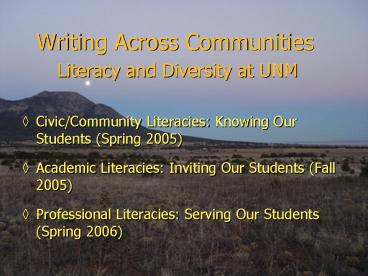

Writing Across Communities Literacy and Diversity at UNM

Description:

Civic/Community Literacies: Knowing Our Students (Spring 2005) ... CASA Latina (1994-1996) Teachers for a New Era. Washington Center for Teaching and Learning ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:124

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Writing Across Communities Literacy and Diversity at UNM

1

Writing Across Communities Literacy and

Diversity at UNM

- Civic/Community Literacies Knowing Our Students

(Spring 2005) - Academic Literacies Inviting Our Students (Fall

2005) - Professional Literacies Serving Our Students

(Spring 2006)

2

Renewing Our Commitment to

Addressing the Needs of Local

Communities

- CASA Latina (1994-1996)

- Teachers for a New Era

- Washington Center for Teaching and Learning

- (Co-Director, 2004-Present)

- Successful Schools in Action (2004-Present)

- Campaña Quetzal (2004-Present)

3

Compaña Quetzal Latino Education

Summit Resolutions

- On Community Empowerment and Participation

- On Parent Leadership and Involvement

- On Early Childhood Education

- On the Cultural, Linguistic, and Academic Needs

of the Latino Community

4

Latino Education Summit Resolutions, continued

- On Disproportionality in Discipline

- On College Support

- On Recruitment of Latino Instructional Staff

- On Proyecto Saber

- On State and Federal Obligations

5

Creating Pathways to Academic Literacy and Beyond

- Situating the Personal, Professional, and

Political - Juan C. Guerra

- Department of English

- University of Washington at Seattle

6

Expanded WAC/WID programs at most universities

typically consist of four components

- First-year writing (introduction to academic

discourse, topic seminars) - Student support (writing center, course-based

tutoring) - Upper-level courses (writing in the disciplines)

- Faculty development (seminars, consultations,

course approval) - (adapted from Parks

Goldblatt, 2000)

7

Most universities could create a writing

across communities program by adding the

following components

- Service and experiential learning

- K-16 connections

- Community literacy projects

- Literacy research

- Technology leadership

- Business and professional outreach

- (adapted from Parks

Goldblatt, 2000)

8

Philosophical Principles

Informing the Work

of Transforming Cultures of Writing

Across Communities First

Principle We must work to dismantle the

barriers that separate the university from

local communities. From the standpoint of

the child, the great waste in the school comes

from his or her inability to utilize the

experiences he or she gets outside of the

school in any complete and free way within the

school itself while, on the other hand, he

or she is unable to apply in daily life what he

is learning at school. John

Dewey Dewey in Education, 1899/1998

9

Second Principle Because it occupies a

position of power in the larger community and

possesses the necessary resources, the

university must work to address the literacy

needs of the multiple communities that it

serves. What Im describing might be

called the New American College, an institution

that celebrates teaching and selectively

supports research, while also taking special

pride in its capacity to connect thought to

action, theory to practice. This New

American College would organize

cross-disciplinary institutes around pressing

social issues. Undergraduates at the college

would participate in field projects,

relating ideas to real life. Classrooms and

laboratories would be extended to include

health clinics, youth centers, schools and

government offices. Faculty members would

build partnerships with practitioners who would,

in turn, come to campus as lecturers and

student advisors. The new American

College, as a connected institution, would be

committed to improving, in a very

intentional way, the human condition. Ernest

Boyer Creating the New American

College Chronicle of Higher Education, 1994

10

Third Principle Everyone involved in

the process of developing a writing across

communities program must engage in a shared and

mutually productive critique of public

education. A network of people concerned

with literacy in a region could develop a

supportive and constructive critique of public

education that would make solutions possible

across traditional educational and community

boundaries.

Steve Parks Eli Goldblatt

Writing Beyond the Curriculum

Fostering

New Collaboration in Literacy

College

English, 2000

11

The Rhetorical Practice of Transcultural

Repositioning Transcultural

repositioning is a rhetorical ability that

members of disenfranchised communities often

enact intuitively but must learn to regulate

self-consciously, if they hope to move

productively across different languages,

registers, and dialects different social and

economic classes different cultural and artistic

forms and different ways of seeing, being

in, and thinking about the increasingly fluid

and hybridized world emerging all around us.

Juan Guerra Putting Literacy in its

Place Nomadic Consciousness and the

Practice Of Transcultural Repositioning

Rebellious Reading The Dynamics of

Chicana/o Cultural Literacy, 2004

12

The Roots of Transculturation

- When he first coined the concept of

transculturation in 1947 as an alternative to the

concepts of assimilation and acculturation,

Fernando Ortiz posited that the result of every

union of cultures is similar to that of the

reproductive process between individuals the

offspring always has something of both parents

but is always different from each of them. - In 1991, Mary Louise Pratt described

transcultuation as the processes whereby members

of subordinated or marginal groups select and

invent from materials transmitted by a dominant

or metropolitan culture. While subordinate

peoples do not usually control what emanates

from the dominant culture, they do determine to

varying extents what gets absorbed into their own

and what it gets used for. - Vivian Zamel argued in 1997 that transculturation

reflects precisely how languages and cultures

develop and change--infused, invigorated, and

challenged by variation and innovation.

13

The Roots of Repositioning

- According to Min-Zhan Lu (1990), each student

writer has access to a range of discourses--the

discourses used in college and in other cultural

sites, such as home, workplace, high school,

neighborhood, among religious, recreational,

peer, or gender groups. - Moreover, conventions and meanings intersect and

conflict both within and between these

discourses. - In negotiating their way through these

conflicting terrains, Lu contends that students

have three options they may 1) choose to

assimilate the academys ways of thinking and

writing 2) choose the path of biculturalism or

3) see writing as a process in which the writer

positions, or rather, repositions herself in

relation not to a single, monolithic discourse

but to a range of competing discourses.

14

A better understanding of cultural diversity can

enhance our students ability

- To write appropriately . . .

- with an awareness of discourse

conventions - To write productively . . .

- by achieving their social and

material aims - To write ethically . . .

- by becoming attuned to the

cultural ecology around them - To write critically . . .

- by engaging in inquiry and

discovery - To write responsively . . .

- by responsibly negotiating the

tensions of exercising authority

15

The Personal

- Before we arrive at the university, each of us

learns how to communicate with others in the

context of a situated community whose members

share an identity and a set of linguistic and

cultural values. These are then reflected in - Our participation in local languages and dialects

- Our enactment of local literacy practices

- Our interactions with members of other discourse

communities

16

The Professional

- The university is one of the many sets of

discourse communities that we engage in the

course of our social and personal development.

There, we - Learn the language of the academy

- Are initiated into a discipline and prepare for a

- professional career

- Acknowledge the likelihood of multiple career

changes

17

The Political

- Besides preparing us for a career, a

university education also prepares us to engage

in the civic discourses - of our local, state, and national

communities. We initiate and carry out this

process by - Reconnecting with a local community

- Identifying its particular needs

- Addressing the communitys needs through a shared

theory of action