DIMENSIONS OF CONTESTATION IN THE EUROPEAN UNION - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 52

Title:

DIMENSIONS OF CONTESTATION IN THE EUROPEAN UNION

Description:

Location: Paasivirta Lecture room, Department of Contemporary History ... Uncontested votes, negative votes and abstentions by member state (% of all decisions) ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:108

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: DIMENSIONS OF CONTESTATION IN THE EUROPEAN UNION

1

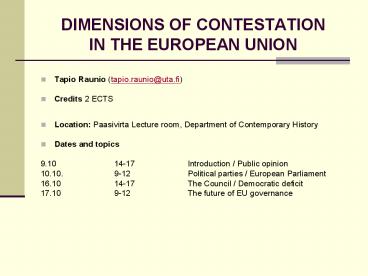

DIMENSIONS OF CONTESTATIONIN THE EUROPEAN UNION

- Tapio Raunio (tapio.raunio_at_uta.fi)

- Credits 2 ECTS

- Location Paasivirta Lecture room, Department of

Contemporary History - Dates and topics

- 9.10 14-17 Introduction / Public opinion

- 10.10. 9-12 Political parties / European

Parliament - 16.10 14-17 The Council / Democratic deficit

- 17.10 9-12 The future of EU governance

2

INTRODUCTIONWhy study dimensions of

contestation(or lines of conflict) in the

European Union?

- While the EU can be characterized as a consensual

polity (multiple checks and balances), its

outputs (laws, non-binding decisions, foreign

policy etc.) are nonetheless the product of

bargaining between actors that have policy goals

shaped by their ideological dispositions - Media seldom pays attention to the dimensions of

politics in the EUs political system (notably in

the Council or the Parliament) or to the reasons

why certain member states favour / oppose

decisions - Media far too often provides a simplified picture

of reality e.g., Poland is a difficult country

in the EU, or Swedes oppose further

integration

3

Consensus democracy and supermajorities

- Constitutional (Treaty) amendment is subject to

unanimity, with all member states having the

power of veto this basically rules out

large-scale reforms - EU has no government or president the European

Council is the collective executive board of

the Union. The European Council decides with

some exceptions - by unanimity - The role of the Commission in initiating and

implementing legislation is overseen by national

governments, whose civil servants participate in

the hundreds of committees and working groups

that draft the EUs legislative initiatives and

oversee their eventual implementation - The Council decides most issues by QMV (over 70

of votes), but its working methods are still

consensual, with emphasis on building compromises

acceptable to all or nearly all governments

4

- The Council is still far more powerful than the

European Parliament - Consultation procedure is still the most common

legislative procedure (EP only consulted) - The two chambers are equal only in matters

falling under the co-decision procedure (used in

under half of EU legislation depending how one

measures the share of issues processed according

to the co-decision procedure) - Co-decision procedure involves two readings in

both institutions, following which a conciliation

committee is convened if no agreement has been

reached. In the second reading the Council

decides by QMV and the EP by absolute majority

(50 1 of all MEPs) - Decision rules are reflected in the work of the

institutions in both the Council and the EP the

emphasis is on building broad consensus (laws

based on supermajorities) - No opposition Example how can citizens oppose

Common Agricultural Policy? Would require the

election of parliamentary majorities opposed to

CAP in all or nearly all member states!!

5

Chains of representationin the EUs political

system

- The national channel

- Citizens ? national parliament ? government ?

Council / European Council - The European channel

- Citizens ? European Parliament ? Commission

6

Co-decision procedure

7

PUBLIC OPINION ONEUROPEAN INTEGRATION

- Basic premises

- The political elites (MPs, MEPs, parties,

business and administrative elites) are more

pro-integrationist than citizens - Low salience of EU for voters (permissive

consensus?) - Weak attachment to the EU hardly any feeling of

a political community - Citizens knowledge of how EU functions remains

very limited (particularly regarding

decision-making) - Public support for integration remained at a high

level until the early 1990s - Highest levels of Euroscepticism are normally

found in the UK, Sweden, Austria, and Finland --

and also in some of the new member states

8

- Explanatory factors

- Utilitarian calculations (perceived benefits) are

usually seen as the strongest explanatory factor - those that benefit from trade liberalization

support integration - those that otherwise benefit from the removal of

borders support integration - The popularity of the national government or

the state of the national economy influences

support for the EU - Identity is becoming more important if citizens

have an exclusive (national) identity, they are

more likely to be critical of integration - New member countries transition winners are

likelier to support integration

9

REFERENDA ON EU MEMBERSHIP

10

Referenda and European Integration

- Domestic context and factors impact on voting

behaviour in EU referenda and EP elections and

also explain to some extent public opinion on

integration - Why the French voted against the Constitutional

Treaty on 29 May, 2005? (turnout 70 , 55

against the Constitution) - Outcome mainly explained by

- French economy worries about unemployment,

relocation of businesses, and the decline of the

French social model (and lack of social

dimension in the Treaty) and - opposition to the government and the president

(which were in favour of the Constitutional

Treaty) - Argument even though the citizens may overall be

supportive of integration, referenda provide them

the opportunity to protest against particular

aspects of integration (e.g., Turkeys potential

membership)

11

Irish referendum on the Treaty of Lisbon

- Irish referendum on 12 June 2008 53 against,

47 in favour. Turnout was 53 - All three government parties supported the 'Yes'

campaign. So did all opposition parties in the

parliament, with the exception of Sinn Féin. Most

Irish trade unions and business organisations

also supported the 'yes' campaign - Ireland was the only member state that held a

referendum on the Treaty (in addition to a

parliamentary vote) - Outcome probably explained by a combination of

domestic (resignation of PM Ahern due to

corruption pro-EU consensus of the political

elite worries about economy) and European

(fears of tax harmonisation and common EU

defence agricultural policy) reasons - Citizens also suffered from lack of information ?

Ahern's successor PM Brian Cowen admitted that

not even he had read the text of the Treaty!

12

Image of the EU (Eurobarometer 69, spring 2008)

13

Support for membership

14

Public opinion IIElites versus the citizens

- Hooghe, Liesbet (2003) Europe Divided? Elites

vs. Public Opinion on European Integration.

European Union Politics 43, 281-304. - Elites (both national and European) are by and

large more supportive of European integration

than the citizens - How should authority be distributed between the

EU and national governments? - Elites favour a European Union capable of

governing a large, competitive market (currency,

single market) and projecting political muscle

(foreign and defense policy) - Citizens are more in favour of a caring European

Union, which protects them from the vagaries of

capitalist markets

15

- Elites and public preferences are similar in that

both are least enthusiastic about Europeanizing

high-spending policies such as health, education,

or social policy -- shifting authority in these

policies could destabilize powerful vested

interests and disrupt policy delivery - However, the public wants to Europeanize

market-flanking policies, and elites do not - As the single market intensifies labor market

volatility, the public seems intent to contain

this other distributional risk through

selectively Europeanizing policies that flank

market integration employment, social policy,

cohesion policy, environment, and industrial

policy - The views of elites are consistent with a

functional rationale, which conceives integration

as an optimal solution for reaping economies of

scale the policies elites want to Europeanize

most are currency, foreign policy, development

aid, immigration, environment, and defense

16

POLITICAL PARTIES ANDEUROPEAN INTEGRATION

- European integration has not altered the basic

structure of national party systems by resulting

in the formation of new parties - But, most national parties are divided over EU

for example, the main British and French parties

have experienced serious internal disputes on

integration matters since the 1950s - There are very strong reasons to expect that we

would not witness the entry of new parties as a

result of European integration -- or any other

issue for that matter - The main explanatory factor for the observed

stability is that the established national

parties have an interest in sustaining the status

quo and the prevailing structures of party

competition

17

- Parties that are successful in the existing

structure of contestation have little incentive

to rock the boat, while unsuccessful parties,

that is, parties with weak electoral support or

those that are locked out of government, have an

interest in restructuring competition. The same

strategic logic that leads mainstream parties to

assimilate the issues raised by European

integration into the Left/Right dimension of

party competition leads peripheral parties to

exploit European integration in an effort to

shake up the party system. (Hooghe et al. 2002

970) - Does ideology or country-specific factors explain

how parties view European integration? - The standard finding has been that of an inverted

U-curve, with opposition to European integration

found at the extreme ends of the left-right

dimension while more centrist parties are

supportive of further integration - This implies that party family is a powerful

predictor of party positions on EU

18

- Centrist party families are in favour of

integration - Leftist parties -- particularly social democrats

but also greens and the radical left -- have

become considerably more pro-integrationist since

the early 1990s - Leftist parties want to counterbalance economic

integration with increasing the EUs role in

social and environment policies, while the

centre-right parties focus primarily on EMU

(broad agreement about the deepening of

integration) - According to recent studies deeper integration

enjoys more support among representatives of

leftist parties - Opposition to the EU is mainly the reserve of

anti-system or ideologically more radical

(extreme left or right) parties these parties

find it difficult to establish regular

cooperation with each other largely the same

group of parties that are excluded from

government in their countries

19

- However, more recent research has partially

challenged this argument, particularly as a

result of the enlargement that took place in 2004 - Marks et al. (2006) show that another cleavage,

the GAL (Green / alternative / libertarian) -TAN

(traditional / authoritarian / nationalist)

dimension is a strong predictor of parties EU

positions -- with opposition to further

integration mainly found among extreme left/right

and TAN parties - There are important differences between the old

member states and those that joined the Union in

2004. In the West, the leftist parties tend to

be GAL parties while rightist parties are more

TAN in their orientation. In the East, on the

other hand, opposition to the EU is primarily

concentrated among a group of left/TAN parties

20

Domestic structure of party competition and

positioning on European integrationWest vs.

East(Vachudova Hooghe 2006)

21

Domestic structure of party competition and

positioning on European integrationWest vs.

East(Vachudova Hooghe 2006)

22

PARTY POLITICS INTHE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT

- Compared with parties in EU member state

legislatures, the party groups of the European

Parliament operate in a very different

institutional environment - There is no real EU government accountable to the

Parliament - There are no coherent and hierarchically

organized European-level parties - MEPs are elected from lists drawn by national

parties and on the basis of national electoral

campaigns - The social and cultural heterogeneity of the EU

is reflected in the internal diversity of the

groups, with a total of 170 national parties from

25 member states winning seats in the Parliament

in the 2004 elections

23

- However, despite the existence of such factors,

EP party groups have gradually over the decades

consolidated their position in the Parliament - At the same time the shape of the party system

has become more stable, at least as far as the

main groups are concerned. One can thus talk of

the institutionalization of the EP party system

- Throughout its history the EP party system has

been based on the left-right dimension - Initially the party system consisted of only

three groups socialists/social democrats (PES),

Christian democrats/conservatives (EPP), and

liberals (ELDR), the three main party families in

most EU member states - Since the first direct elections also the Greens

and the group of the radical left parties, now

titled the Confederal Group of the European

United Left / Nordic Green Left (EUL-NGL), have

become institutionalized in the chamber - Moreover, Eurosceptical parties, parties whose

main reason of existence is opposition to further

integration, have formed a group under various

labels since the 1994 elections

24

Seat distribution in the EP after the 2004

elections

25

- The EP groups achieve rather high levels of

voting cohesion (around 90 ) - The main cleavage structuring competition in the

Parliament is the familiar left-right dimension,

the main dimension of contestation in European

democracies (Hix et al. 2007) - While the primary decision rule in the EP is

simple majority (50 1 of those voting), for

certain issues (mainly budget amendments and

second reading amendments under the co-decision

procedure) the EP needs to muster absolute

majorities (50 1 of all MEPs) - The absolute majority requirement facilitates

co-operation between the two main groups, EPP and

PES, as the surest way of getting the required

number of MEPs behind the Parliaments decision

is when the two large groups agree on the issue - Cooperation between EPP and PES could also be

regarded as a sign of maturity, as the

Parliament needed to moderate its resolutions in

order to get its amendments accepted by the

Council and the Commission. After all, the

overwhelming majority of national ministers

represented in the Council and members of the

Commission are either social democrats or

Christian democrats/conservatives - However, in recent years (particularly after the

1999 EP elections) this co-operation has played a

lesser role than before, with EPP and PES

opposing each other more often regardless of the

voting rule but still the two large groups vote

together most of the time

26

Life in the post-enlargement 2004-2009 EP has

anything changed? (Based primarily on Hix and

Noury 2008)

- Enlargements (2004 and 2007) have increased the

number of MEPs 626 to 785. These MEPs represent

27 countries and around 180 parties - The increase in heterogeneity of membership

plausibly leads to less predictable and less

stable voting patterns. Moreover, it may

complicate coalition formation across national

lines - Some scholars argue that political parties in the

new Central and Eastern European member states

are not easily placed in party families based on

durable ideological cleavages such as the

left-right conflict - Around 60 of MEPs from the new member countries

are members of the PES and the EPP. In general,

there is little evidence that formal affiliations

are markedly different for the new members (but

note the lack of green MEPs from the new member

states)

27

Life in the post-enlargement 2004-2009 EP has

anything changed? (Based primarily on Hix and

Noury 2008)

- In general party cohesion has remained very

stable - The EPP and PES voted together almost exactly the

same amount of times in the 1999-2004 EP (65 of

the time) and in the first 18 months of the

2004-2009 Parliament (67 of the time) - In the 2004-2009 Parliament there has (so far)

been a clearer centre-right majority bloc

(ALDE-EPP/ED-UEN), while the three leftist groups

(PES, G/EFA, EUL/NGL) have been in a minority

position and have also been less united - Certain nationalities exhibit a stronger tendency

to vote against the group line Polish, British,

Danish, Swedish, and Czech MEPs

28

VOTING AND COALITIONS IN THE COUNCIL (OF

MINISTERS)

- Based primarily on Mattila, Mikko (2008) Voting

and Coalitions in the Council after the

Enlargement. In Daniel Naurin Helen Wallace

(eds) Unveiling the Council of the EU Games

Governments Play in Brussels. Palgrave Macmillan

Basingstoke (forthcoming) - How has the accession of ten new member states in

2004 affected decision-making in the Council? - How has the contestation of decisions changed and

what is the role of the new member states in this

potential change? - Has the introduction of ten new members affected

coalition formation in Council voting? - How do the new members fit into the existing

political space of Council interaction?

29

- Data roll call records of the Council during the

whole period of the EU25 from May 2004 to the end

of 2006 - During this period the Council decided on 416

legislative acts and 942 other acts. Of these

about 38 were decisions, 32 regulations, 8

directives, 6 joint actions and the rest

consisted of various other types of decisions

(resolutions, common positions, declarations,

agreements etc.) - Of all the decisions in the data set about 90

were agreed upon unanimously. Negative votes were

given in 8.9 and 6.2 of cases, respectively.

This means that the share of contested decisions

has not increased after the enlargement - One interpretation of this would be that the ten

new member states have been very quick to

internalise the prevailing norms of the EU

decision making, particularly the culture of

consensus

30

Uncontested votes, negative votes and abstentions

by member state( of all decisions)

31

Multidimensional scaling map of Council voting

32

- The overall alignment of member states in the

Figure points to the existence of a north-south

dimension that affects voting patterns in the

Council. The situation has not changed in any

significant way when compared to the time before

the enlargement - At least tentatively, these results show that the

fears of a gridlock in Council decision-making in

the enlarged union were exaggerated - However, one should not draw too far-reaching

conclusions from this analysis - Roll-call data can provide only a limited and

rather superficial picture of the way the Council

operates. In order to evaluate the effects of the

enlargement in its entirety these results should

be supplemented by a more thorough analysis of

the content of contested Council decisions. In

addition, qualitative analyses based on

interviews and participant observations could

show how the day-to-day interaction in Council

bargaining has changed - Note also that bargaining in the Council (the

political space) differs most likely from

bargaining in Intergovernmental Conferences and

in the European Council!

33

DEMOCRATIC DEFICIT?

- Does the EU suffer from a democratic deficit?

- Moravcsik, Andrew (2002) In Defence of the

Democratic Deficit Reassessing legitimacy in

the European Union. Journal of Common Market

Studies 404, 603-624. - Follesdal, Andreas Simon Hix (2006) Why There

is a Democratic Deficit in the EU A Response to

Majone and Moravcsik. Journal of Common Market

Studies 443, 533-562. - How to make the EU more democratic? the answer

depends on what kind of Europe one wants

(intergovernmental or supranational or

something in between?) - Note national political systems also have

serious problems of their own most notably

falling participation rates and the (alleged)

move towards spectator or audience democracy

34

Definitions of the democratic deficit

- Broader definition or meaning

- limited role of the citizens in the EUs policy

process or - weak connection between public preferences and

EUs decisions - The institutional definition

- weak role of directly-elected institutions

(national parliaments and the European

Parliament) - The electoral dimension

- no election really focuses on European matters

- referendums do, but opinion is divided on whether

they should be used in integration matters

(agenda manipulation) - Lack of a European public sphere

- no European media

- no real European parties

- no European debates or European language!

35

Defending supranational democracy

- Not a state, may never be one not a federation,

but operates increasingly like federal systems - Yet the EU to an increasing extent carries out

functions traditionally associated with

independent countries - Foreign and security policy

- Trade policy

- Citizenship and legal system

- Currency etc.

- A constitution that defines the competence of

the EU the jurisdiction of the Union covers

nearly all policy areas from cultural exchange

programmes to security policy - The EU already possesses significant

policy-making powers hence there should be

competition for leadership of the Union - Democracy is good for its own sake it will also

contribute to the gradual emergence of a European

identity

36

Does the EU need input (democracy) or does its

legitimacy depend on outputs (results)?

- But arguably most issues that are salient for

European voters are still decided nationally

(taxation, health care, education, social and

employment policies etc.) - National politicians use the EU for solving

domestic problems, with the oversight of common

interest delegated to supranational agents

(Commission, ECJ) - Lack of common identity

- The success of integration depends primarily on

the ability of the EU to produce efficient

outputs peace and stability, economic growth,

removal of barriers to trade, counterweight to

globalization and excesses of capitalism - Low turnout in EP elections is used as an

argument against strengthening supranational

democracy

37

THE FUTURE OFEU GOVERNANCE

- Limited capacity for change constitutional

amendment subject to unanimity, thus ruling out

large-scale reforms - Asymmetry of national preferences the final

outcome of IGCs reflects the configuration and

intensity of national objectives - Institutional questions have proven more

problematic than transfer of competencies

(compare with USA and Philadelphia in 1787) - Producing supranational laws through the

Community method or relying increasingly on

intergovernmental policy coordination? - The purpose of the following comparison is to

identify the strengths and weaknesses of these

two modes of EU governance, and to examine how

genuine supranational democracy would work in the

EU

38

OPTION ICommunity method

- The Community method is the expression used

for the institutional operating mode for the

first pillar of the European Union - It has the following salient features1)

Commission monopoly of the right of initiative

2) General use of QMV in the Council - 3) An active role for the European Parliament in

co-legislating frequently with the Council - 4) Uniformity in the interpretation of Community

law ensured by the Court of Justice - The method used for the second and third pillars

is similar to the so-called intergovernmental

method, with the difference that the Commission

shares its right of initiative with the Member

States, the European Parliament is informed and

consulted and the Council may adopt binding acts.

As a general rule, the Council acts unanimously.

39

OPTION IIIncreasing use of soft law and

(intergovernmental) policy coordination

- The growing use of the open method of

coordination (OMC) and other forms of policy

coordination common objectives defined by member

states and the EU, monitoring by the EU

institutions, and implementation and choice of

instruments for meeting the objectives delegated

to member states - While intergovernmental policy coordination has

been a feature of the EUs decision-making system

throughout the history of integration, such

informal policy coordination has become much more

prominent since the early 1990s - The European Employment Strategy (EES) adopted at

the Essen European Council in 1994 and the

coordination of national economic policies agreed

in the Maastricht Treaty extended this

coordination to two highly salient issue areas of

domestic politics

40

- OMC became officially a part of EU jargon at the

Lisbon European Council in 2000 - OMC has four main components

- 1) Fixed guidelines set for the EU, with short-,

medium-, and long-term goals - 2) Quantitative and qualitative indicators and

benchmarks - 3) European guidelines translated into national

and regional policies and targets and - 4) Periodic monitoring, evaluation and peer

review, organized as a mutual learning process - In recent years OMC has been applied to a broad

range of policies, including employment, social

policy, environment, taxation, immigration,

research, social protection, education, social

infrastructure, regional cohesion, and social

inclusion

41

- The increasing use of OMC and other forms of

informal, non-binding, primarily

intergovernmental soft law instruments needs to

be understood in the context of the sensitive

question of dividing competencies between the EU

and its member states - European integration has reached the stage where

the core areas of welfare state, such as social

policy, employment, and education are starting to

be affected. In these policy areas (that are both

money-intensive and touch core areas of national

sovereignty) it is very difficult to build the

needed consensus among national governments for

transferring policy-making authority to the

European level -- hence the resort to

intergovernmental policy coordination - The national governments want, on the one hand,

to achieve highly-valued policy objectives, such

as reducing unemployment and making their

economies more competitive, while on the other

hand they are not willing to cede formal

sovereignty to the Union

42

- The Commission sees these new modes of governance

as a way to expand EUs competence in the face of

resistance from the member states - The literature on OMC and other forms of soft law

instruments or new modes of governance is

already quite extensive, and it has produced

three main findings - 1. It is still too early to make any definitive

assessments of the success of OMC. Scholars

usually point that, unlike top-down supranational

legislation, it is flexible and (supposedly)

respects subsidiarity and national autonomy. The

down-side of this non-binding nature of outputs

is that the EU has few if any means to make

national governments follow its recommendations - 2. OMC has strengthened the leadership role of

the Council (and the European Council) the

Commission has a central role to play through its

role as the institution setting objectives and

issuing guidelines to national governments

43

- The EP has until now been effectively

marginalized, and, the contribution of local and

regional actors, often identified as the main

stakeholders in these processes, has so far been

quite disappointing. At the national level OMC

seems to be the preserve of a fairly small circle

of civil servants that possess expertise on the

issues. - 3. It appears that the actual impact of OMC and

other forms of informal policy coordination has

so far been relatively modest, if not even

inconsequential, in many policy areas - Trade-off between efficiency and democracy

cooperative federalism and intergovernmental

policy coordination can be seen as decision

methods prioritizing efficiency. However, the

decision process is removed from the public

sphere to intergovernmental meetings taking place

behind closed doors. As a result, cooperative

federalism weakens the transparency of collective

decision-making and, hence, the accountability of

the representatives

44

Comparing the two modes of EU governance

- Agenda setting and proposal power

- In supranational legislation the Commission

basically has the monopoly of initiative, but

obviously its initiatives are largely based on

instructions from the Council and the European

Council. The OMC is much more a tool to be used

collectively by the member states, but here too

the EU institutions mainly the Commission and

the Council set the agenda and coordinate

subsequent actions - Policy competence

- In supranational legislation the competence

belongs to the EU, whereas the OMC is primarily

used in policy areas where the Union has no

access to binding legislation - Decision rule

- Most supranational legislation is passed nowadays

in the Council by QMV, but in OMC processes

issues are decided by mainly by unanimity

45

- The role of the European Parliament

- The EP performs an increasing role as a

co-legislator in producing supranational laws,

but it is merely consulted (or kept informed) in

OMC - Bureaucrats vs. elected office-holders

- Civil servants are central actors in both types

of governance. However, in the OMC their role

appears to have been far more influential, with

much less guidance and instructions from members

of government - Openness and transparency

- The European Parliament meets in public the

Council is gradually moving towards deliberating

and voting on laws in public. OMC processes are

conducted behind closed doors - Policy learning

- As the OMC produces non-binding outputs, it has a

higher capacity for policy learning. In

supranational legislation the same solution

applies throughout the Union (with the partial

exception of directives)

46

OPTION IIITwo models of supranational democracy

- a) Parliamentary model

- Parliamentary system the government is

accountable to the parliament (and can be voted

out of office by the latter) - The members of the lower house (EP) would be

directly elected the people while the upper

house/senate (Council) would consist of either

directly-elected representatives (as in the U.S.

Senate) or of government representatives (as in

the German Bundesrat) - Government formation would be based on elections

to the lower house and the cabinet would have to

enjoy the confidence of the lower house (or

alternatively, of both houses)

47

- For the parliamentary model to work effectively,

four criteria should be met - 1) The choices offered to voters should be

identical throughout the Union (common Europarty

manifestos) - 2) The elections should be contested on the basis

of issues relevant to the Union - 3) Democratically elected party leaders would

head the campaigns (who would also be potential

future prime ministers) - 4) The party groups of the Europarties should be

cohesive enough to enable the government to

execute its programme once in office - The effective performance and durability of the

executive would require a hierarchical, cohesive

party organisation, and it is unlikely that this

would happen without giving the Europarties the

right to influence or determine candidate

selection

48

- The Commission would have to be the real EU

government, thus reducing the powers of the

European Council - But, would majoritarian parliamentary democracy

work in a Union characterised by strong national

identities (and a weak European identity)? - This potential problem could be alleviated by

- 1) A constitutional rule guaranteeing all

countries representation in the government as

they currently have an own commissioner - 2) Bicameralism and demanding parliamentary

voting rules (absolute majorities, QMV) in

certain questions (like in Germany) - Would change fundamentally the role of the

Commission by making it a party-political

institution (and not anymore so much a neutral

defender of the common EU interest or a guardian

of the Treaties)

49

- Government formation after the 2004 EP elections

- Alternative 1

- Grand coalition between EPP and PES (note the

absolute majority rule in the Parliament) - This would be the safest option in terms of

building the needed majorities, but it would also

lead to a weak opposition (particularly if the

ELDR was also in the government) - Alternative 2

- Centre-right coalition between EPP, ELDR (ALDE),

and possibly Greens and UEN - Alternative 3

- Centre-left minority coalition between PES,

EUL/NGL, and Greens (and possibly liberals)

50

- b) Presidential model

- Importing the U.S. presidential system to the EU

- The presidential model would not put similar

pressure on the EP party groups to achieve

unitary behaviour, but would require EU-wide

parties that would each put forward a single

candidate - While this reform would undoubtedly improve the

leadership capacity of the Commission (when

coupled with strengthening its competence), it

might also lead to a two-party system, at least

in the presidential elections - The winner would either be the candidate

receiving the plurality of the votes or then a

second round would be organised between the most

successful candidates if none of the candidates

gets a majority of the votes (as in France) - 1st round candidates by EPP, PES, ELDR, Greens,

radical left (EUL-NGL), and anti-EU parties 2nd

round most likely EPP and PES

51

Predicting the Future

- Strengthening parliamentarism by (a) tying the

formation of Commission more explicitly to the EP

elections -- this will also become the

constitutional rule should the Lisbon Treaty

enter into force and (b) extending the use of

co-decision procedure and QMV in the Council - Simultaneously most of the member states and

their main parties emphasize maintaining the

European Council (and the Council) as the leading

decision bodies. The presidential version

receives only very marginal support - OMC, together with other forms of soft law,

will be used to an increasing extent

particularly as it is so difficult to transfer

new law-making powers to the European level

52

FINAL QUESTIONS

- 1) Will the unanimity rule in amending the

Treaties and in other important matters lead to

increasing use of flexibility (enhanced

cooperation)? According to the Lisbon Treaty at

least 1/3 of the member states must want to

co-operate, and others must be free to join - 2) Should EU have a stronger role in carrying out

redistributive policies? Are the EU citizens

willing to support active EU fiscal or regional

policies (compare with Belgium, Canada and

Switzerland)? Note the lack of common identity

(emotional attachment) or feeling of a political

community! - 3) How to connect citizens to EU decision-making?

In EP elections parties have campaigned primarily

on domestic political issues. EU questions are

marginalized also in national elections, and thus

no electoral forum focuses directly on EU. More

precisely, should constitutional amendment be

subject to referendum?