PHL105Y November 28, 2005 - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 30

Title:

PHL105Y November 28, 2005

Description:

... things as causally connected; it is natural or instinctive for us to do so. ... of the Principle of the Uniformity of Nature is thoroughly instinctive. ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:42

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: PHL105Y November 28, 2005

1

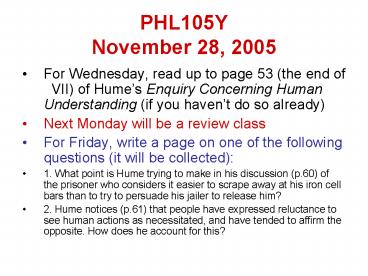

PHL105YNovember 28, 2005

- For Wednesday, read up to page 53 (the end of

VII) of Humes Enquiry Concerning Human

Understanding (if you havent do so already) - Next Monday will be a review class

- For Friday, write a page on one of the following

questions (it will be collected) - 1. What point is Hume trying to make in his

discussion (p.60) of the prisoner who considers

it easier to scrape away at his iron cell bars

than to try to persuade his jailer to release

him? - 2. Hume notices (p.61) that people have expressed

reluctance to see human actions as necessitated,

and have tended to affirm the opposite. How does

he account for this?

2

Section 7

- Of the idea of

- necessary connection

3

Where ideas come from, again

- all our ideas are nothing but copies of our

impressions it is impossible for us to think of

any thing, which we have not antecedently felt,

either by our external or internal senses (41)

4

Where ideas come from, again

- Even complex invented ideas (with no

corresponding complex impressions), are

ultimately composed of simple ideas, and so can

ultimately be traced back to simple impressions

Hume thinks that going back to the original

impressions can cast light on any complex idea

5

So, where do we get the idea from?

- Single observations of causation just show us one

event, then the other, without making the bond

between them visible - But what about repeated observations of events of

type A followed by events of type B? - (How could repetition yield anything new?)

6

So, where do we get the idea from?

- After repeated observations of events of type A

followed by events of type B, the mind is

conscious of something new the mind itself has

changed, following the course of experience, and

feels the force of custom or habit pushing it to

think of B when it sees A

7

Where we get the idea of cause

- after a repetition of similar instances, the

mind is carried by habit, upon the appearance of

one event, to expect its usual attendant, and to

believe, that it will exist. The connection,

which we feel in the mind, this customary

transition of the imagination from one object to

its usual attendant, is the sentiment or

impression, from which we form the idea of power

or necessary connection. (50)

8

What we really mean when we say A causes B

- When we say, therefore, that one object is

connected with another, we mean only, that they

have acquired a connection in our thought.

(50-51) - So the only difference between the match striking

causing the flame and a pair of causally

unrelated events happening one after the other is

that in the causal case I feel an easy, customary

transition in my own thinking

9

Our surprising ignorance

- And what stronger instance can be produced of

the surprising ignorance and weakness of the

understanding, than the present? For surely, if

there be any relation among objects, which it

imports to us to know perfectly, it is that of

cause and effect. On this are founded all our

reasonings concerning matter of fact and

existence. (51)

10

Scepticism about causes

- As far as causal connections are concerned, we

are not detecting anything really out there in

nature we are not calculating anything about

what is really out there in in nature we are

just feeling something in ourselves. - Does this mean we should stop thinking things are

causally connected? Is our causal thinking

invalid?

11

Causes and reasons

- Even if our causal thinking is not founded on any

reasoning about how things are in the world, we

cannot stop seeing things as causally connected

it is natural or instinctive for us to do so. We

feel that nature is full of causal connections,

that things must happen in this order, even

though we are unable to construct rational proofs

to support these feelings of ours.

12

Causes and reasons

- Although we cant prove that nature is governed

by causal necessity, we instinctively feel that

it is these feelings of ours in fact enable us

to go on and reason about nature. - So, buried at the heart of science is a deep

assumption that is not founded on reason our

acceptance of the Principle of the Uniformity of

Nature is thoroughly instinctive. (But this

doesnt mean we should give it up and in fact

we cant give it up, if Hume is right.)

13

Section 8

- Of Liberty and Necessity

14

The problem of freedomPhilosophical, not

practical

- Hume contends that in daily life we have a clear

understanding of liberty and necessity, and the

relation between them - Philosophical theories of freedom have left us

confused because the terms freedom and

necessity have been misused and poorly defined

15

How we reason about nature

- If nature kept changing so that every event was

totally different from every past event, wed

never get the idea of necessity or causation.

16

How we reason about nature

- If nature kept changing so that every event was

totally different from every past event, wed

never get the idea of necessity or causation. - Regular, recurring patterns give us the feeling

of causation and enable us to reason about nature.

17

Physical nature and human nature

- We are able to reason about nature because it is

uniform and regular nature is under thorough

causal necessity

18

Physical nature and human nature

- We are able to reason about nature because it is

uniform and regular nature is under thorough

causal necessity - We are able to reason about human nature because

it is uniform and regular human nature is under

thorough causal necessity

19

Human nature is predictable

- The same motives always produce the same

actions The same events follow form the same

causes. Ambition, avarice, self-love, vanity,

friendship, generosity, public spirit these

passions, mixed in various degrees, and

distributed through society, have been, from the

beginning of the world, and still are, the source

of all the actions and enterprises, which have

ever been observed among mankind. (55)

20

Human nature is predictable

- Would you know the sentiments, the inclinations,

and course of life of the Greeks and Romans?

Study well the temper and actions of the French

and English. (55)

21

Character as well as circumstance

- Ones behaviour is determined not simply by ones

outward setting, but also by ones internal

character (also conceived causally) - Custom, education, training, etc. control how we

will respond (so men and women might react

differently in the same setting or members of

different cultures) (57)

22

Deviations from character?

- Nice people can sometimes be mean, suddenly

- Stupid people can sometimes be lively and charming

23

Deviations from character?

- Nice people can sometimes be mean, suddenly

- when they have toothaches

- Stupid people can sometimes be lively and

charming - when they have just won the lottery

24

Matter and action

- Hume argues for a complete parallel between the

total causal order we see in physical nature and

causal determination of our actions we expect

uniformity in both cases, and we steadily make

causal inferences (unsupported objects will fall,

people prefer more money to less, etc.)

25

Matter and action

- Where we see apparent failures of uniformity, or

where our inferences go wrong, we dont suppose

that theres no causal order we suppose that

there are some hidden factors we havent yet

spotted. Erratic behaviour in humans is treated

just as we treat erratic phenomena in geology (we

dont in fact suppose that people act uncaused).

See p.60.

26

True or false?

- If you leave a 50 bill unattended on a table in

The Meeting Place for an hour during lunch rush,

the odds that it will still be sitting there at

the end of the hour are about the same as the

odds that the table will have floated into space

27

True or false?

- If you leave a 50 bill unattended on a table in

The Meeting Place for an hour during lunch rush,

the odds that it will still be sitting there at

the end of the hour are about the same as the

odds that the table will have floated into space - Human actions obey some laws of gravity as much

as tables do.

28

What is liberty?

- Why dont we want liberty or free action to be

uncaused action?

29

What is liberty?

- Why dont we want liberty or free action to be

uncaused action? - Notice in particular, that there is a problem if

free actions are not connected to our motives or

desires

30

What is liberty?

- a power of acting or not acting, according to

the determination of the will. - You have this unless you are physically

restrained from doing what you want to do. - (Are there any problems with this definition of

liberty?)