9. FIRE - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 94

Title: 9. FIRE

1

9. FIRE

2

Introduction

- Many fires are associated with the use of

high-risk materials and, through ongoing

legislation should result in continuing

improvements - it often takes several years before older,

high-risk materials are replaced. - In large or tall buildings, the much higher

potential risk resulting from reduced access of

emergency services has long been recognized

through again, fires still occur, sometimes due

to failure of one or two parts of the structure

to prevent fire spread. - Increasing attention is now being given to fire

stops in cavities, ducts and roof spaces.

3

Combustion

- Three prequisites for a fire are

- Fuel

- Oxygen

- Heat

- 1. Fuel

- Almost all organic materials behave as fuels.

- Carbon and Hydrogen are the main constituents so

that the materials rich in these will be a

greater hazard and especially those rich in

hydrogen, such as oil products and gas, since

hydrogen generates more heat than carbon.

4

- 2. Oxygen

- This is present in the form of air, diluted with

nitrogen which is inert. - Pure oxygen, sometimes stored in cylinders is

highly dangerous. - 3. Heat

- Heat causes

- Chemical decomposition of most organic materials

releasing volatile vapor. This effect is called

PYROLYSIS. - Reaction between both the solid and vapour

fraction and oxygen - C O2 ? CO2 heat (solid fuel)

- CH4 2 O2 ? CO 2H2O Heat (hydrocarbon fuel)

- These are combustion processes though it is the

reaction of vapor with oxygen together with

accompanying light emission that is described as

a FLAME

5

Flame

- They are not necessary for fire but their

pressure usually increases the severity of a

fire. - Because

- Gases have much greater mobility than solids so

that flames help spread the fire. - The temperature in a flame is very high- usually

? 1200oC.

6

Ignition

- The application of sufficient heat will initiate

the combustion process, which then generates more

heat and ultimately, when the temperature is high

enough, ignition or flaming will occur.

7

Fire and Density

- The ideal for habitable buildings might be

considered to be avoidance of all combustible

materials. - Normally totally impracticable

- because organic materials are inseparably linked

to human comfort furniture, furnishings,

clothing- and to human activity-books paper and

implements. - In many cases for reasons of economy and/ or

convenience the enclosure itself will involve

combustible materials (wooden floors, doors,

window frames and partitions).

8

Fire Load

- The risk presented by the combustible contents of

an enclosure is defined as FIRE LOAD. - Fire Load total mass of combustible contents

in the enclosure - expressed as wood equivalent per unit floor area.

- Fire Load Comb.mass/(m2 (floor))

- Higher fire loads produce longer duration fires.

9

- Fire Severity

- Depends on

- Type and decomposition of combustible material,

- Ventilation characteristics

- good ventilation may reduce the durability of

fires by venting heat.

10

Development of Fires

- Damage of fire depends on

- situation which give rise to it,

- the way in which it develops and spreads.

- In the early stages of most fires, spreading is

largely the result of flaming and localized heat

generation, - hence it requires materials which are not only

combustible but in a flammable form.

11

Flashover

- It is the most important stage in any fire (See

Figure 9.1). - Occurs when the air temperature in the enclosure

reaches about 6000C. - At that point, pyrolysis (vaporisation) of all

combustable materials takes place so that they

all become involved in the fire and flaming

reaches dramatic proportions, limited only by the

total fuel available and/or by the supply of air.

12

Figure 9.1 BS476 tests relating to initiation,

growth, and spread of an uncontrolled fire in the

compartment of origin.

13

- In many such fires, flaming occurs mainly outside

windows using to lack of air internally and this

helps spread the fire upwards to adjacent floors

of the building. - A priority in design for fire resistance is to

prevent or delay flashover since there is little

change of survival in an enclosure once this has

occurred.

14

- The thermal inertia of the surfaces of an

enclosure is an important factor - highly conductive, heat absorbent materials such

as brick, help to delay the temperature rise as

well as being non-combustible. - Flashover may be prevented in poorly ventilated

closures due to lack of air for combustion, or

delayed in very large ones where there are large

volumes of air in relation to available fuel-they

have a cooling effect. - It is estimated at present that the fire services

arrive before flash-over in about 90 of fires.

15

Fire Tests

- Fire tests attempt to classify materials and

components in relation to fire performance and

form the basis of Building Regulations. They

cover 2 chief areas - 1. The development and spread of fire.

- These tests include combustability, ignitibility,

fire propogation, spread of flame and heat

emission of combustible materials. - 2. Effects of fire on the structure, adjacent

structures and means of escape, the first

priority in any fire being the safety of the

occupants. - These tests are concerned with the structural

performance of buildings, their ability to

contain the fire and problems associated with

smoke.

16

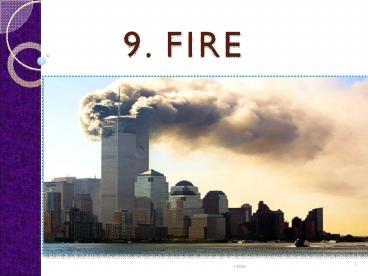

- Many of the above aspects are covered by BS476,

Figure 9.2. A brief resume of the contents of

parts relating to fire spread in current Building

Regulations is given in Table 9.1. - Examples on fires

- Collapse of World Trade Centers (New York)

17

Figure 9.2 Five ways in which fire can be

initiated.

18

Table 9.1 BS476 tests relating to fire

development and spread referred to in current

Building regulations.

19

BURNING OF CONCRETE

20

After Fire

- the amount of debris,

- blackening of the structure,

- Peeling,

- loss of finishes,

- can give the impression that the concrete

elements are severely damaged.

21

Assessing fire-damage

- An inspection of the site including limited

non-destructive testing, sampling and laboratory

investigation to produce a repair classification

for each element. - Experienced practitioner can obtain a significant

amount of information during a site inspection. - Laboratory investigation is often critical to

establish the temperature achieved at different

depths in the concrete and thus the condition of

that element. - An indispensable technique is the investigation

in petrographic examination.

22

General considerations

- Loss of strength and modulus of elasticity

- Concrete looses strength on heating.

- Residual strength of a concrete element after a

fire depends on several factors, for temperatures

up to 3000C the residual strength of

structural-quality concrete is not severely

reduced. - Concrete is unlikely to possess any useful

structural strength if it has been subjected to

temperatures above 5000C, the strength then being

reduced by about 80.

23

- Typically, concrete made with lightweight

aggregate does not lose significant strength

until 500oC. - The effects of a fire on modulus of elasticity

are similar to the effects on strength. - Up to 300oC, the modulus of elasticity is not

severely reduced but by 800oC it may be as little

as 15 of its original value (85 loss).

24

Effects of fire on reinforcement

- Steel looses strength on heating but

reinforcement is often protected from the effects

of fire by the surrounding concrete, which is a

poor thermal conductor. - Steel reinforcement suffers a reduction in yield

strength at temperatures above 450oC for

cold-worked steel and 600oC for hot-worked steel.

- Prestressed steel looses tensile strength at

temperatures as low as 200oC and by 400oC may be

at 50 of normal strength. - Buckling of reinforcement can occur at high

temperatures if there is restraint, for example

by adjacent elements, against thermal expansion.

25

Spalling of concrete after fire

- In a fire, most concrete structures spall to some

extend, although lightweight aggregate concretes

are usually more resistant. - The surface can scale in the early stages of a

fire as the near-surface aggregate splits as a

result of physical or chemical changes at high

temperatures. - Explosive spalling also occurs in the early

stages of a fire but involves larger pieces of

concrete violently breaking away from the surface

and may continue from areas already spalled. Such

spalling usually results from high moisture

content in the concrete. - The thermal shock of a cold water on to hot

concrete during fire-fighting can also induce

spalling.

26

Depth of damage

- Concrete is a poor thermal conductor and so high

temperatures will initially be confined to the

surface layer with the interior concrete

remaining cooler. - At corners where two surfaces are exposed to the

fire, the effect will penetrate further because

of the transmission of heat from the two

surfaces. - If concrete spalls early in a fire, the depth of

effect from the original surface will be greater

than if the concrete does not spall or if

spalling occurs later in the fire.

27

Damage assessmentSite inspection

- Various features of the concrete and associated

materials in the fire-affected locations must be

noted and from these a visual classification of

the damage produced. - The Concrete Society report (CSTR 33) includes a

useful numerical classification and this is shown

in a simplified format in Table 9.2

28

Table 9.2. CSTR 33 classification of fire damage.

29

Damage assessmentSite inspection

- Firstly, the condition of any plaster or other

surface finishes is noted. - Surfaces may be sooty but otherwise unaffected by

the fire. - As the effects become more severe, the finishes

start to peel until they are completely lost or

destroyed. - Likewise, during the fire the concrete surface

will progressively craze until it is lost. - The concrete color may also be affected during

the fire, generally changing with increasing

temperature from normal through pink to red, then

whitish grey and finally buff.

30

- The pink and red colours relate to the presence

of small amounts of iron in some aggregates,

which oxidise and can be indicative of particular

temperatures. - It is important to note that many concreting

aggregates do not change colour at temperatures

normally encountered in an ordinary fire. - Although colour change clearly indicates a

particular temperature, the absence of colour

change does not mean that the temperature was not

reached.

31

Other site investigation requirements

- Cores - or, if these are not possible, lump

samples - should be taken for laboratory

investigation from a number of locations

representing the range of damage classifications

observed and should include comparable unaffected

concrete as a control. - Laboratory petrographic examination is necessary

to support and enhance the site findings.

32

- The depth of cover to any reinforcement must be

measured during site investigation so that, once

the laboratory investigation has been completed,

it will be possible to determine whether the

steel is likely to have been affected by the

fire. - It is also possible to take steel samples for

laboratory analysis, but this is usually

necessary only if the visual inspection reveals a

cause for concern.

33

Laboratory investigation petrographic examination

- Petrographic examination should be conducted by

someone experienced in the technique and in

examining fire-damaged concrete, and is best

performed in accordance with ASTM C856. - An initial low- to medium-power microscopic

examination of all cores allows the selection of

those for thin-section preparation and more

detailed examination with a high- power

microscope.

34

- As well as identifying physical distress such as

cracking, this examination can identify features

that allow temperature contours' to be plotted

on the concrete. - Binocular examination allows contours to be

plotted that equate to around 300C provided the

aggregate has become pink, the colour deepening

to brick-red between 500C and 600C.

35

- Any flint in the concrete calcines (loses its

water component, about 4 ) between 250C-450C,

while at similar temperatures the normally

featureless cement paste begins to show patchy

anisotropy with yellow-beige colours. - Thus, careful and informed petrographic

examination can usually reveal an

approximate 500C contour. - Cracking of the surface of the concrete occurs at

relatively low temperatures, but deep cracking

indicates around 550C was reached.

36

- Quartz alters structurally at 575C resulting in

a volume increase that typically causes extensive

fine microcracking. - As most concrete contains quartz, an approximate

600C contour can usually be plotted. - The change in colour from brick-red to grey also

begins at 600oC. - Limestone aggregate calcines at 800C and

concrete becomes a buff colour by 900C.

37

Laboratory investigation

- Another laboratory technique sometimes used to

assess the temperature reached is

thermo-luminescence. - Based on the fact that quartz emits visible light

when heated to 300-500C, unless it has already

been heated to that temperature. - It is be possible to establish the depth to which

the concrete has been affected. - The usefulness of this method is somewhat reduced

by its limited availability and cost. - However in special circumstances,

thermo-luminescence is invaluable, despite the

expense.

38

Overall assessment

- The visual damage classification prepared on site

provides the basis for a repair strategy. - However the laboratory investigation -

particularly the petrographic temperature

contouring - provides critical information about

the depth of any fire damage, and any

classification of damage should be reviewed after

the laboratory investigation. - Critical temperatures (T) are as follows

- T gt300oC considerable loss in strength of the

concrete. - T 200-400C considerable loss of strength of

prestressed steel. - T gt450oC loss of residual strength of

cold-worked steel. - T gt600C loss of residual strength of hot-rolled

steel.

39

Options for repair requirements for demolition

- Detailed information about repair is given in

CSTR 33. - A brief guide to the level of repair required can

be based on the final classification of damage. - On the basis of practical experience, Figure 9.3

has been devised to illustrate the types of

repair that might be appropriate for different

classes of damage.

40

World Trade Centre - New York - Some Engineering

Aspects

- General Information

- Height 417 meters and 415 meters

- Owners Port Authority of New York and New

Jersey.(99 year leased signed in April 2001 to

groups including Westfield America and

Silverstein Properties) - Architect Minoru Yamasaki, Emery Roth and Sons

consulting - Engineer John Skilling and Leslie Robertson of

Worthington, Skilling, Helle and Jackson - Ground Breaking August 5, 1966

- Opened 1970-73 April 4, 1973 ribbon cutting

- Destroyed Terrorist attack, September 11, 2001

41

(No Transcript)

42

(No Transcript)

43

(No Transcript)

44

(No Transcript)

45

(No Transcript)

46

(No Transcript)

47

(No Transcript)

48

(No Transcript)

49

Figure 9.3. Simplified illustration of

Classification and Repair.

Some peeling of finishes, slight crazing minor

spalling. Class 1 rapair slight damage.

Total loss of finish, Whitish grey

colour, Extensive crazing, Considerable spalling

up to 50 reinforcement exposed, minor cracking,

class 3 principal repair involving strengthening.

Much loss of finish, pink colour, crazing, up to

25 reinforcement exposed, class 2 restoring

cover to reinforcement with general repairs

reinforced with light fabric

Plaster paint intact, Class 0 clean

redecorate if required.

Finishes destroyed, buff colour, surface lost,

almost all surface spalled, over 50

reinforcement exposed, major cracking. Class 4

major repair involving strengthening or

demolition replacement.

50

- EXAMPLE from Cyprus

51

TRNC Ministry of Culture Education, Turkish

Cypriot State Theatre Hall

Theatre Hall- after fire, 2006

52

State Theatre Hall /Lefkosa-After fire in 1999

duration 20 minutes only

53

State Theatre Hall /Lefkosa-After fire in 1999

54

State Theatre Hall /Lefkosa-After fire in 1999

55

State Theatre Hall /Lefkosa-After fire in 1999

56

State Theatre Hall /Lefkosa-After fire in 1999

57

State Theatre Hall /Lefkosa-After fire in 1999

58

State Theatre Hall /Lefkosa-After fire in 1999

59

Theatre Hall after fire, 2006

60

Theatre Hall after fire, 2006

61

- More examples

62

Caracas Fire

63

Taiwan

64

Interstate bank

65

Madrid

66

Madrid

67

Meridian Plaza

68

The Windsor Building Fire, Madrid, SpainHuge

Fire in Steel-Reinforced Concrete Building Causes

Partial Collapse

Time Collapse Situation 129 East face of the

21st floor collapsed 137 South middle section of

several floors above the 21st floor gradually

collapsed 150 Parts of floor slab with curtain

walls collapsed 202 Parts of floor slab with

curtain walls collapsed 211 Parts of floor slab

with curtain walls collapsed 213 Floors above

about 25th floor collapsed Large collapse of

middle section at about 20th floor 217 Parts of

floor slab with curtain walls collapsed 247 South

west corner of 1 2 floors below about 20th

floor collapsed 251 Southeast corner of about

18th 20th floors collapsed 335 South middle

section of about 17th 20th floors collapsed

Fire broke through the Upper Technical

Floor 348 Fire flame spurted out below the Upper

Technical Floor 417 Debris on the Upper

Technical Floor fell down

69

Sunday, Jan. 10, 2016 photo, the burned hulk of

The Address Downtown is seen in Dubai, United

Arab Emirates. Skyscraper fires like the blaze

that struck the 63-story luxury hotel in Dubai on

New Year?s Eve, 2016, swiftly turning it into a

towering inferno, are not that rare. The fire in

Dubai has raised new issues about the safety of

exterior sidings put on high-rise buildings in

the United Arab Emirates and around the world.

(AP Photo/Jon Gambrell)

70

Assessment of fire damaged structuresBRE

Information Paper IP 24/81

- Buildings, or portions of buildings, look a

sorry sight after a fire - some may have collapsed and be only twisted

ruins, others may have mainly suffered damage

from smoke. - Between these extremes there is a wide range of

degree of damage. - Where there is no visible damage such as

charring of timber, spalling of concrete or

distortion of steelwork, there is generally

little likelihood of permanent loss of

strength of the material although this cannot

always be assumed. - It is essential to do a thorough inspection of

the complete premises in order to ensure that

damage, - eg through thermal expansion or water leakage,

has not occurred in those parts not directly

involved in the fire.

71

TEMPERATURES REACHED IN FIRES AND ESTIMATION OF

FIRE SEVERITY

- Standard fire resistance tests determine the

period of time for which elements of building

construction should fulfill their design function

of load bearing and / or fire separation while

exposed to heat in accordance with a

predetermined time / temperature relationship is

an idealisation of an uncontrolled growing fire

in a room. - It assumes an unlimited supply of fuel and its

burning rate, being controlled mainly by

ventilation condition, follows a predictable

pattern.

72

- In real incidents, fire may have remained

localised for a long time, the rate of

temperature rise may have been faster, or slower,

than in the standard test, or extensive spread

may occur. - Different rooms and different parts of a building

may have suffered different fire intensities. - It is important to determine as accurately as

possible the condition of each element of the

structure following the fire. - Particular attention also needs to be given to

those features which are an indirect consequence

of the fire, - eg forces not considered in the orginal design

may have been generated by expansion or damage to

other members.

73

- Table 1 gives an approximate guide to the

estimation of temperatures attained by various

components in building fires, from an examination

of debris.

74

(No Transcript)

75

- The colouration of concrete at various depths is

a clue to both the maximum surface temperature

attained (Figure 1) and the time / temperature

experience (Figure 2). - Care and experince are required when considering

spalled surfaces. - The interpretation will depend on judgement as to

whether spalling occured during the period of

maximum heat exposure or subsequently, and as to

the allowance to be made for this factor. - The extent of the change of colour varies with

the type of fine and coarse aggregate but changes

will occur to some degree for all types of

concrete. - Wetting the affected concrete surface will

enhance the colours. Some types of stone shows

similar changes.

76

(No Transcript)

77

(No Transcript)

78

- The depth of charring from the orginal surface

gives a rough guide to the duration of fire

attack on a timber member. - Timber will char at a steady rate on each face

exposed to heating. - The rates which are given in Table 2 relate BS

476Part 8 conditions and allow an assessment to

be made in terms of an equivalent fire resistance

time. - Increased values are appropriate for the rate of

depletion of columns and beams when exposed on

all faces. - Due allowance must be made for areas which have

been allowed to smoulder after the fire has been

controlled.

79

- With palsterboard of 9.5 mm thickness, the

unexposed paper face will be charred if there

has been a fire equivalent in severity to about

ten minutes under BS 476 Part 8 conditions.

80

MAIN EFFECTS OF HIGH TEMPERATURE ON MATERIALS

- any material heated above 200oC is likely to show

significant loss of strength which may, or may

not, be recovered after cooling.

81

Brickwork

- Clay bricks withstand temperature in the region

of 1000oC or more without damage but under very

severe and prolonged heating the surface of a

brick may fuse. - Spalling can occur with some types of brick

particularly of the performed type. - A load bearing wall exposed to fire will suffer a

progressive reduction in strength due to

deterioration of the mortar in the same manner as

concrete. - Severe damage is more likely to be caused by the

expansion or collapse of other members. - Small expansion cracks in the structure may

collapse up after the building has cooled.

82

Cast Iron

- Because of their heavy mass and low design

stresses, cast iron members generally show good

performance in fires. - The member should be carefully examined for signs

of cracking. A permanent loss of strength can

occur when the temperature of a cast-iron member

exceeds 600oC but because of their large thermal

mass this requires a fire of such severity that

rebuilding is probably necessary anyway.

83

Concrete

- The behaviour of concrete structures in fire is

discussed elsewhere5.6. The pink colour change at

around - 300oC which occurs with most natural aggregates

used in the UK is very important as it coincides

with the temperature below which the compressive

strength is not significantly reduced. Higher

temperatures up to approximately 500oC or above

may be endured by lightweight concrete before

significant loss of strength occurs. In a

concrete member, only the temperature of the

outside layers increases initially and the

temperatures of the internal concrete will be

comparatively low, unless the fire exposure is

prolonged, as concrete is a poor conductor of

heat (Figure 2). Temperature rise at a greater

depth than indicated in that figure will occur if

extensive spalling occurs during fire exposure.

Natural aggregate concretes heated to - 300oC or above, and lightweight aggregate

concretes heated to 500oC or above, may need to

be replaced in - critical areas during reinstatement.

84

Steel Reinforcement

- Looses strength at high temperatures as discussed

below. Loss in effective concrete section in

prestressed members may significantly alter the

intended design stress profile in addition to

permitting a higher temperature in any adjacent

steel tendons with consequent increased loss.

85

- Hollow clay tiles and woodwool cement slabs (used

in floors) - may be damaged but when these are used as formers

for the structural concrete section they have no

structural significance and the damage can be

ignored. - Plaster

- Plaster tends to be loosened in a fire and may

require replacement for this reason. - If it is severely stained by smoke which is

resistant to washing, it will probably be more

satisfactory to replace the plaster than to

overpaint the smoke stains.

86

Steel

- When a building has been exposed to fire the

structural steelwork may suffer from any or all

of the following effects - a) expansion of heated members relative to

others which restrain this movement, leading to

distortion of the heated member or its neighbours

particularly at connection, - b) increased ductility, reduced strength and

plastic flow while metal is at a high

temperature, - c) change, persisting after cooling, in the

mechanical properties of the metal. - The coefficient of linear thermal expansion of

steel is nominally 14 X 10-6/0C. In a fire this

may be sufficiently small for it to be taken up

by elastic deformation, expansion joints etc, or

may permanent distortion of the framework or

extensive cracking of bearing walls.

87

- The temperature at which the flow stress of mild

steel falls to the design stress is generally

taken to be about 550oC - - for a design factor of safety of about 2. At

stress levels less than the maximum permitted in

design, this critical temperature will rise.

The effects of constraints and continuity can

also raise the critical temperature. - Unless temperatures of 650oC are exceeded, there

will be no deterioration in the mechanical

properties of mild and micro-alloyed steels on

cooling. - After heating cold-drawn and heat-treated steels

lose their strength more rapidly than mild and

micro-alloyed steels and, on cooling from

temperatures in excess of about 300oC and 400oC

respectively, part of this loss of strength will

be permanent.

88

- In general, any steel members which have

not distorted can be considered to be

substantially unaffected by the heat to which

they have been subjected. However, it must be

realized that in certain cases some degradation

in strength will have occurred. - Members should be examined for cracks around

rivet or bolt holes if expansion movements have

taken place. - It will usually however, be the cleast, rivets

and especially bolts which will have suffered and

not the main members. - Decision on reinstatement may need to be taken in

the light of expert engineering and metallurgical

advice.

89

- Tiles and slates

- Clay tiles that have survived a fire unbroken may

be reused, as can slates that appear sound. - Timber

- Behaviour of timber in fire is predictable with

regard to the rate of charring and loss of

strength. - It is free from rapid changes of state and has

very low coefficient of thermal expansion and

thermal conductivity. - For practical purposes, it can be assumed that

full strength is maintained below the charred

layer. - For assessment of fire resistance of structural

timber, BS 52683 provides calculation methods for

flexural, compressive and tensile members.

90

(No Transcript)

91

Woodwool cement

- The material below the crumbly fire damaged layer

will be sound. - If a sufficient depth of sound material is

present the slabs may be retained.

92

ASSESMENT OF EXTENT OF DAMAGE AND POSSIBLE

REINSTATEMENT

- A design procedure for the reinstatement of fire

damaged buildings is given elswhere also a case

study on building reinstatement. - The problems caused by fire will of course

include damage from water used in fire fighting

as well as from heat and smoke.

93

- The initial consideration of fire damaged

premises should classify the damage to building

components in terms of superficial, repairable or

requiring replacement. - In any investigation, it is essential to

determine the exact form of construction of each

element. - Specialist advice may be needed in cases where

there is much borderline repairable damage or

where the construction is sophisticated. - The final decision on the extent of repair or

demolition may include consideration of costs,

time and possible improvements.

94

REFERENCES

- 1. British Standars Instution. Fire tests on

building materials and structures. Test methods

and criteria for the fire resistance of elements

of building construction. BS 476 Part 81972

London. BSI 1972 - 2. Bessey GE. Investigation on building fires.

Part 2. The visible changes in concrete or mortar

exposed to high temperatures. National Building

Studies Technical Paper No 4 . London, HMSO,

1950. - 3. British Standards Instution. The structural

use of timber. Fire resistance of timber

structures. Method of calculating fire

resisitance of timber members. BS 5268 Part 4.

11978. London, BSI, - 1978.

- 4. Lie T T. Fire and Buildings. Applied Science

Publisher Ltd. London, 1978. - 5. Asseement of fire damaged concrete structures

and repair by gunite. Concrete Society Technical - Report No 15. The Concrete Society. London,

1978. - 6. Green J K. Some aids to the assessment of

fire damage. Concrete. January, 1976. - 7. Smith C I et al. The reinstatement of fire

damage steel framed structures. British Steel

Corporation - Research Organization. Teeside Laboratories.

1980. - 8. Malhotra H L and Morris W A. An investigation

into the fire problems associated with woodwool

permanent shuttering for concrete floors.

Building Research Establishment Current Paper

CP68/78. Borehamwood, 1978. - 9. Marchant E W ( Editor). A complete guide to

fire and buildings. Medical and Technical

Publishing - Co Ltd. Lancaster, 1972.