323 Morphology - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

Title:

323 Morphology

Description:

323 Morphology The Structure of Words 2. Basic Concepts (Last updated 25 SE 06) 2.1 Lexemes and Word Forms Words are not easy to define. A preliminary definition is ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:118

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: 323 Morphology

1

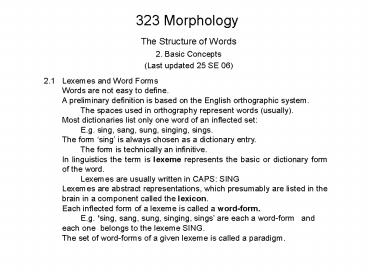

323 Morphology

- The Structure of Words

- 2. Basic Concepts

- (Last updated 25 SE 06)

2.1 Lexemes and Word Forms Words are not easy to

define. A preliminary definition is based on the

English orthographic system. The spaces used in

orthography represent words (usually). Most

dictionaries list only one word of an inflected

set E.g. sing, sang, sung, singing,

sings. The form sing is always chosen as a

dictionary entry. The form is technically an

infinitive. In linguistics the term is lexeme

represents the basic or dictionary form of the

word. Lexemes are usually written in CAPS

SING Lexemes are abstract representations, which

presumably are listed in the brain in a component

called the lexicon. Each inflected form of a

lexeme is called a word-form. E.g. sing, sang,

sung, singing, sings are each a word-form and

each one belongs to the lexeme SING. The set of

word-forms of a given lexeme is called a

paradigm.

2

2.1 Lexemes and Word Forms

By convention in each language, the dictionary

representation may be the infinitive form of the

verb as in Russian, the first person singular in

Latin (which has no infinitive), the third person

singular in Arabic, or perhaps by some other

form. The entry form for nouns in normally the

singular nominative case form of the noun Latin,

Russian, English, Czech, German. A lexeme

family, or less formally a word family, is a set

of lexemes that are related. They should share

some phonological properties and be related

semantically. The latter is easier said than

determined. E.g. print, printable, unprintable,

printer, printability, reprint. This list is not

necessarily complete. Complex lexemes are

lexemes formed with an affix (a morpheme). E.g.

able, un, er, ity, re in the above

list. Complex lexemes must each be listed

separately in a dictionary as the meaning may

differ. The various word-forms of a given

lexeme do not change the meaning of the

lexeme. Which affixes that occur with which

basic lexeme is not predictable. E.g. we find

in English un-happy, un-ripe, but not un-sad,

un- red, un-tall, and so forth.

3

2.1 Lexemes and Word Forms

Sometimes a lexeme with an affix occurs but the

basic form does not exist E.g. dis-gruntled

but not gruntled, in-cognito, but not cognito,

un-gainly, but notgainly. Sometimes the

expected affix does not occur but another affix

does E.g. natural-ness in place

natural-ity. Or the expected affix occurs with

another meaning E.g. cook, cook-er (an

instrument for cooking, not a person who

cooks, which is simply the noun

cook. Kinds of morphological

relationship inflection the relationship

between the word-forms of a lexeme. E. g. mask,

masks sit, sat, sitting, sits blue, bluer,

bluest. derivation the relationship between

lexemes of a lexical family. E. g. singer,

singer write, writer cookV, cookN,

cooker. Derivation usually implies forming one

lexeme from another lexeme in the same lexical

family. E.g. sing -gt singer, write -gt writer,

cookV, cookN and cooker. Word is used whenever

the distinction between derivation and inflection

is uncertain. (no examples currently). Compound

lexeme) refers to words that are made up of two

or more lexemes doghouse, catfish, greenhouse,

whiplash, tattletale, and so forth.

4

2.2 Morphemes

A morpheme is the smallest constituent with a

function. I prefer this distinction to smallest

constituent with meaning. There are some forms

that appears to be constituents but have no

discernable meaning, but have a function in terms

of word building E.g. doof-us, radi-us, cf.

radi-al, radi-an. Some inflectional morphemes

have no true meaning, but they have a grammatical

function E.g. he, him who, whom they,

them, The suffix -m marks the accusative

(objective) Case. This is a syntactic relation

and no meaning can be associated with it. The

term function includes meaning. To go one step

further than H., the hierarchy for constituents

is Sentence -gt phrase -gt word -gt

morpheme. Phrases are very important constituents

in syntax. Some grammatical categories cannot be

expressed in terms of morphemes. For example,

note the following partial inflection of the

English verb sing and others similar to

it E.g. sing, sang, sung. The past tense is

marked by a change of the root vowel. The latter

form marks two distinct grammatical functions

the passive form of the verb and the perfect form

of the verb. Each form is a distinctive morpheme

with a different function but phonologically the

same.

5

2.3 Affixes, Bases and Roots

Affixes are morphemes that are adjoined to the

left of the base of a word or to the right of the

base of a word A prefix is an affix that is

adjoined to the left of the base of a

word. E.g. un- in un-happy, un-regulated

re- re-do, re-heat, re-write, and so

forth. A suffix is an affix that is adjoined

to the right of the base of a word. E.g. s in

book-s, cat-s eat-s, smell-s linguistic-s. An

infix is an affix that is inserted into the base

of the word forming a non- contiguous base.

There are no infixes in English. Infixes occur in

the Semitic language. E. g. ktb is the base

for book and read and words which refer to

book/read in some related sense. To form the

noun in Arabic, the infixes I and a are

inserted into the base between the firsts two

consonants and the second two consonants,

respectively E.g. kitab. A circumflex is an

affix that occurs on both sides of the base.

(H.) E. g. (per H) German ge-les-en. English

dialects a-walk-ing, a-read-ing.. The English

a- is etymologically related to the German

ge-. Actually, this is not quite the case. In

German the prefix ge- is a morpheme and

allomorph in that it occurs in other

constructions. The prefix ge- must occur in

construction with certain suffixes. A circumflex

is a morphological construct which contains a

prefix and a suffix in a noncontiguous string.

Together the affixes in a circumflex represent

one function. Outside of the aforementioned

dialect, there are no circumflexes in English.

6

2.3 Affixes, Bases and Roots

Stem and Root A root is a morpheme that cannot

be broken down into further morphemes. A base

is a contiguous strings of one or more morphemes

which can hold lexical meaning. In English the

word dog, for example, is a root since it cannot

be broken into further morphological

units E. g. do is not a morpheme of dog, it

is basically a verb. There is no morpheme og

that has any kind of function. Dog is also a

base. It has lexical meaning. The English word

disgruntled consists of three morpheme dis-,

gruntle, and ed. dis is a prefix, and ed is an

inflectional affix marking the past tense among

other functions. The morpheme gruntle is a root,

since two affixes are adjoined to it. It is not a

base, since it has no lexical meaning (what does

gruntle mean?) Once both affixes are adjoined to

it, then disgruntled, which is a base, is a

lexical stem since it does have

meaning. Technically, the prefix dis- is

adjoined first to gruntle to form the base

disgruntle. Apparently this form has no

lexical meaning and remains a base. Once the

adjectival suffix -ed is added to disgruntle

then the base receives lexical meaning and is a

stem. English has several words usually

considered compounds, where at least one member

of the compound doesnt behave like a normal

prefix or affix. E. g. tele-graph. Although

graph may have lexical meaning, tele- does not.

It does not occur in isolation. The form is

borrowed from Greek where it means far. It is

more like a root that cannot become a stem in its

own right, but it may be adjoined to a stem to

form a new stem. This particular property makes

it look like an affix, or, why are affixes not

roots?

7

2.4 Formal Operations

Some words such as derive imply a process. A true

process is a historical phenomenon and does not

imply a process in terms of how language is

represented in the mind (the grammar of a

language). For some yet to be determined reason,

H considers affixation and compounding to be

concatenative (the addition of morphemes on to a

string e.g. hope-less-ness. Certain kinds of

inflection and other constructions he considers

to be non-concatenative e.g. English sing, sang,

sung (there is no past tense morpheme

here) Another non-concatenative structure

include word whose final consonant becomes

voiced, final consonant becomes palatalized, or

gemination of a root consonant. E.g. Albanian

armik -q (Sg.), armiq -c (Pl.). Note c

is not a palatalized consonant. The form came

about through palatalization, which is not

visible/hearable in the phone c. E.g.

English hoof h?f (Sg.), hooves h?v-z

(Pl.). E.g. Arabic causative verbs darasa

(noncausative), darrasa (causative).

Gemination is the doubling of a consonant.

Reduplication is the copying of a syllable or

part of a syllable 1. Prereduplication E.g.

Ponapean duhp (nonprogressive), du-duhp

(progressive) (be) diving. A weak syllable

(no coda) is copied). 2. Postreduplication. E.

g. Mangap-Mbula kuk (nonprogressive), kuk-uk

)progressive) (be) barking The rhyme of

the syllable is copied. 3. Duplifixing is

adding an affix and reduplicated part of the

stem E.g. Somali buug (Sg.), buug-ag (Pl.)

book(s, fool (Sg.), fool-al (Pl.) .book. The

vowel a is like a suffix in that it is

invariable. The consonants g and l are

copied from the stem final consonant and placed

after a.

8

2.4 Formal Operations

E.g. Tsutujil saq (Sg.) white, saq-soj

whitish. s is reduplicated from the

initial consonant of the stem, and oj is a

nonvariable suffix. Subtraction is the omission

of one or more final segments of the base. E.g.

Murle nyoon (Sg.), nyoo (Pl.) lamb Strong

suppletion is replacing one form with another

form (allomorph) that is phonologically unrelated

to it the replacee. E.g. the forms of the

English verb be is, are, was/were. Weak

suppletion if replacing one form with another

form (allomorph) which share some common

phonological forms, but not all phonological

forms are common to both E.g. sing, sang (/i/,

/æ/), foot, feet (/?/, /i/). Base is redefined

(H) The base of a morphologically complex word

is the element to which a morphological operation

applies. This definition works a long as we

assume a zero operation that may derive one form

from another forms is derived with no

phonological change. We can say a base may be

derived from a root with a zero morphological

operation. E.g. the noun push (he gave me a

push) is derived from the verb push. The

derivation is a zero operation in that there is

no overt sign marking this. We could represent

this as NV PUSH, probably in later

chapters. A morphological pattern refers to the

various ways a particular grammatical or lexical

feature can be expressed. There are four

morphological patterns of the past tense of the

English verb E.g. the default suffix -ed, the

irregular suffix -d (tell, told), ,the

irregular suffix -T (feel, felt), and the vowel

replacement system of strong verbs (sing, sang

drink, drank).

9

2.5 Morphemes and Allomorphs

A morpheme is a set of allomorphs. Most linguists

would agree with this even if they are not

familiar with set theory. The problem is how to

account the variation. For the past 45 years or

so, the theory of underlying representation. This

theory states that there is an abstract (usually)

form from which the other allomorphs are derived.

H refers to these as a fictitious underlying

representation (p.27). H does not elaborate

here. I agree with him. The approach that I

favour is set theory.To review Korean, there are

two allomorphs (members) of the set for the

plural of nouns ul lul (also written as ul

lul. The standard to write morphemes and

allomorphs with hyphens to show that the morpheme

or allomorph is an affix. I is not a theoretical

divergence. As I mentioned before one of the

allomorphs of the plural morpheme is the default.

The nondefault allomorph must be marked with

information indicating the contexts in which the

allomorph occurs. The default allomorph usually

corresponds with the underlying form. The default

or underlying allomorph is normally determined,

in part, at least, by is distribution. There are

fewer vowels than consonants in Korean. If -ul,

which follows consonants, is the default, then

the selection of -lul has a more constrained

condition. The rule writing form will be dealt

with later. In the Russian example on p. 27, H

considers ZAMOK-I castles to be the underlying

form for the plural form. The suffix -ok must

be marked in its grammatical entry (the

grammaticon) to indicate that the vowel /o/ in

the suffix /ok/ is deleted if the inflectional

affix begins with a vowel. I, too, would consider

the allomorph /ok/ as the default. And I would

marked the other allomorph with the same

information indicating that /k/ is chosen if the

suffix begins with a vowel. Lexical conditioning

is the situation where on suppletive (weak or

strong) allomorph is dependent on a particular

lexical item but not on a class. The English

plural -en occurs with only three nouns, one of

them nearly obsolete ox-en, childr-en, and

brethr-en. The suffix the result of a lexical

property called lexical conditioning.

10

2.6 Some Problems in Morpheme Analysis

H mentions a problem arising from suppletion. The

plural allomorphs -s and -en in English are

related by suppletion. They share no exclusive

phonological properties. H raises the question

whether the two suffixes are manifestations of

the same morpheme. H leans toward this view. So

do I. My view is determined by the claim that

all morphemes must have a form, a function and a

sign. I will illustrate with the progressive

participle suffix -ing

The program I am using to make graphics does not

import unicode phonetics. I am using here ñ for

engma, the nasal velar ?. Progressive is the

feature denoting the progressive aspect the form

is a suffix which is adjoined to a noun host

(base) and the sign is /??/. There are plural

signs for nouns in English /z/ and /?n/. These

two allomorphs are strongly suppletive. They are

shown in the following grammeme (entry form for

grammatical morphemes)

11

2.6 Some Problems in Morpheme Analysis

The two allomorphs here form a natural set,

since they share the same function. The fact that

they are the same form supports this claim. If

they are in the same set, then they must be a

member of the Pl. And if they are in the same

set they must be allomorphs. A morpheme may

consist of two or more features. For example, the

English verbal suffix -s marks agreement with a

third person singular subject and it marks the

present tense. The suffix in the above figure

contains two subfeatures Host and Noun.

Agglutinating languages do not do this, with some

minor exceptions. This cumulative expression is

also called fusion. A zero expression ø means

that there is no overt affix to mark a function.

ø has been the topic of notable debates. Until

very recently I was opposed to the notion of ø

until I started learning set theory. Set theory

permits empty sets often written as ø. A zero

expression grammeme is not entirely empty the

sign and the form are empty. It is now considered

better to consider the singular morphological

operation for nouns as ø. It thus has the

following grammemical entry

12

2.6 Some Problems in Morpheme Analysis

Only the function is not empty it merely has no

form and no sign. An empty morpheme is an affix

that has no meaning, but has a function it forms

a base to which certain meaningful affixes are

adjoined. This occurs in English when nouns are

borrowed from Greek and Latin and retain their

plural form. The singular ending occurs in

English an empty (ø) morph E.g. radi-us (Sg.),

radi-i (Pl.) agend-a (Sg.), agend-ae (Pl.)

phenomen-on (Sg.), phenomen-a (Pl.). The plural

form is adjoined to the base, respectively I,

ae, a. In English the Sg. form is

morphologically null. The suffixes in the above

three examples are stem-enders, an empty morpheme

required when there is no suffix adjoined to the

word. This applies to derivatives as well

radi-al, phenomen-al, and so forth. The

grammemical entry for -us is

- Go to Course Outline, Go to Chapter 1, Go to

Chapter 3, Go to Exercise 2