Atlanta, 1973 - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 35

Title:

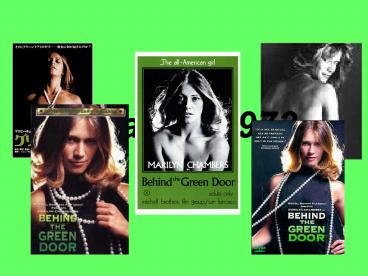

Atlanta, 1973

Description:

Slide 1 ... Atlanta, 1973 – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:78

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Atlanta, 1973

1

Atlanta, 1973

2

Ballew v. Georgia435 US 223 (US 1978)

Georgia Code Ann. 26-2101 (1972)

Distributing Obscene Materials Material is

obscene if considered as a whole, applying

community standards, its predominant appeal is to

prurient interest, that is, a shameful or morbid

interest in nudity, sex or excretion, and utterly

without redeeming social value

3

Ballew v. Georgia435 US 223 (US 1978)

Criminal Court of Fulton County

4

Ballews Motion

- Jury of 5 Constitutionally Inadequate to assess

contemporary standards of the community as to

obscenity. (Not Representative). - Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments require a jury of

at least 6.

O V E R R U L E D

GUILTY

5

Ballew v. Georgia435 US 223 (US 1978)

Supreme Court of Georgia

US SUPREME COURT

Williams v. Florida (US 1970) (6 Member Jury OK)

Court of Appeals of Georgia

Fulton Co. Crim Court

6

The Problem with Williams v. Florida (US 1970)

- Rather than requiring 12 members, then, the

Sixth Amendment mandated a jury only of

sufficient size to promote group deliberation, to

insulate members from outside intimidation, and

to provide a representative cross-section of the

community.

- Although recognizing that by 1970 little

empirical research had evaluated jury

performance, the court found no evidence that the

reliability of jury verdicts diminished with

six-member panels.

The Majority on Williams, from Ballew at 230.

7

The Problem with Williams v. Florida (US 1970)

- Rather than requiring 12 members, then, the

Sixth Amendment mandated a jury only of

sufficient size to promote group deliberation, to

insulate members from outside intimidation, and

to provide a representative cross-section of the

community.

The Empirical Evidence that Size Doesnt Matter?

- Bald assertions and observations of court

officials

- Misinterpreted Studies

5 to 1 ? 10 to 2

- Failure to Account for Representativeness

82 to 32

72 to 47

Michael Saks, Ignorance of Science is No

Excuse (1974)

8

The Problem with Colgrove v. Battin (US 1973)

- Held that Six member juries were constitutional

for Civil cases.

- Relied on Four Empirical Studies, but failed to

critically evaluate the METHODS employed in those

studies.

Michael Saks, Ignorance of Science is No

Excuse (1974)

9

The Problem with Colgrove v. Battin (US 1973)

- Studies 1 and 2

METHOD Compare behavior of 6 and 12 member

juries in jurisdictions where litigants can

choose their jury size.

FINDINGS -No Significant Difference. -12 member

juries deliberate longer, award three times as

much damages, and require twice as much trial

time.

CONFOUNDING FACTOR Attorney Choice

Michael Saks, Ignorance of Science is No

Excuse (1974)

10

The Problem with Colgrove v. Battin (US 1973)

- Study 3

METHOD Compare behavior of 6 and 12 member

juries in a jurisdiction where courts switched

from 12 to 6 member juries.

FINDING -No Significant Difference.

CONFOUNDING FACTORS Mediation Board created at

same time evidentiary rules change.

Michael Saks, Ignorance of Science is No

Excuse (1974)

11

The Problem with Colgrove v. Battin (US 1973)

- Study 4

METHOD A true experiment Randomly composed

mock juries of 6 and 12 members watch a video of

the same case.

FINDING -No Significant Difference.

FLAWS (1)Tiny Sample Size (eight of each) (2)

College Undergrads only (3) Mock Case heavily

weighted to favor defendant.

Michael Saks, Ignorance of Science is No

Excuse (1974)

12

The Courts Social Science Track Record on the

Jury Issue as of 1974

The Court currently believes the matter of

equality of performance for different-size juries

is now well established, when in truth there is

still no evidence to support such a conclusion.

The court and the respective advocates have

consistently failed to exercise the modest

expertise that oculd have prevented this

remarkable incompetence.

Simply an embarrassment.

Michael Saks, Ignorance of Science is No

Excuse (1974)

13

Ballew v. Georgia435 US 223 (US 1978)

The Williams decision spurred a flood of

empirical studies. We have considered them

carefully because they provide the only basis,

besides judicial hunch, for a decision about

whether smaller and smaller juries will be able

to fulfill the purpose and functions of the Sixth

Amendment. (231 FN 10).

14

1.Effective Group Deliberation

Lempert cites various studies, all tending to

suggest that progressively smaller juries are

less likely to foster effective group

deliberation. -The more jurors, the better

collective memory. -The more jurors, the more

likely biases will be counterbalanced and

overcome so an accurate result will be reached.

15

2.Jury Accuracy and Reliability

Nagel and Neef Statistical study- As jury size

shrinks, Type I error (false conviction) rises

and Type II error (false acquittal) shrinks.

Weighing Type I error as 10x more important than

Type II, optimal jury size is six to eight. Five

has high Type I error.

Lempert 12 person juries reach extreme

compromises in 4 of cases 6 person juries reach

extreme compromises in 16 of cases.

16

3. 4. Bias against Defense and Minorities

Zeisel and Lempert Studies Shrinking jury size

from 12 to 6 would cut the number of hung juries

in half. -Criminal Juries tend to hang with one,

but more likely two, jurors remaining

unconvinced. Having an ally makes it much more

likely a person in the minority will stand up for

his or her opinion. -If a minority veiwpoint is

held by 10 of the population, 28.2 of 12 member

juries will have no minority members 53.1 of 6

member juries will have no minority members- only

11 of 6 member panels would have two minority

members, as opposed to 34 of 12 member

panels. -The same numbers hold for minority

representation on the jury.

17

5. Methodological Problems in Studying Jury Size

-Many studies use obvious/clear cases, so

difficult to tell if jury size had any

effect. -Aggregating data can mask Case-by-case

differences in jury deliberations Ex- Judges

hold for plaintiffs 57 of the time juries 59-

seemingly similar. However, case-by-case, judges

and juries disagree 22 of the time. -The

Michigan Study (3 from Colgrove) Average damage

award didnt vary much after the switch from 12

to 6 member juries. But Case-by-case, Damages

Standard Deviation was 58,335 for 6 member

juries and 24,834 for 12 member juries.

18

Ballew v. GeorgiaHOLDING

- the assembled data raise substantial doubt

about the reliability and appropriate

representation of panels smaller than six.

Although the evidence does not draw a bright line

between five and six, any further reduction that

promotes inaccurate and possibly biased

decision-making, that causes untoward differences

in verdicts, and that prevents juries from truly

representing their communities, attains

constitutional significance.

- Queasy feeling about Williams and Colgrove.

19

Ballew v. GeorgiaWrap Up

- Georgia relies on the studies from Colgrove,

whose flawed methodology has been discussed. - There is no pressing state interest to have a

jury smaller than 6- it is not clear that the

time and money saved would be substantial or

worth the risk to justice.

20

Ballew v. GeorgiaConcurrence in the Result

- Also, I have reservations as to the wisdom-as

well as the necessity-of Mr. Justice BLACKMUN'S

heavy reliance on numerology derived from

statistical studies. Moreover, neither the

validity nor the methodology employed by the

studies cited was subjected to the traditional

testing mechanisms of the adversary process. The

studies relied on merely represent unexamined

findings of persons interested in the jury

system. The opinion of Mr. Justice BLACKMUN

acknowledges, in disagreeing with other studies,

that methodological problems may mask

differences in the operation of smaller and

larger juries.

21

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- Issue When to allow the prosecution to impeach

the defendants testimony by telling the jury of

the defendants prior criminal convictions. - The Old Rule Prior convictions can be brought up

if the crime was punishable by death or over one

year in prison, or if it involved theft,

dishonesty, or false statement, regardless of

punishment- AND if the court determines its

probative value on the issue of credibility

outweighs its prejudicial effect on the issue of

guilt. The court must record its reasoning.

(Michigan Rule of Evidence 609 (a) ).

22

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- The Majority finds It is easier for the jury to

find that the defendant is a bad man than that

he actually committed the crime of which he is

accused. Jurors thus have an appetite to (1)

convict a bad man with a criminal past,

regardless of the lack of sufficient evidence (2)

lower the burden of proof due to bad character of

the accused and (3) assume a propensity for crime

is proof of guilt.

23

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- -The Majority also finds

- The thought that Judges Instructions can prevent

jurors from only considering prior convictions

with regard to credibility (and not to overall

guilt) is simply mistaken, as shown by a

number of empirical studies.

24

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- The Dissent challenges the Majoritys assertions

about jurors and limiting instructions and the

methodology of the studies the Majority relies

upon, arguing that the Majority has merely

codified its own opinion on the issue, using

poorly designed studies for a pretext of support.

25

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- Study 1 Hans Doob, Canadian Study

- Method Simulated juries studied.

- Finding Evidence of prior conviction permeates

the entire discussion of the case in spite of

specific instructions to only apply such evidence

to issue of credibility. Jurors barely even used

the evidence with regard to credibility. - Flaw Mock juries and simulations are imperfect

tools for answering empirical questions.

26

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- Study 2 Doob Kirshenbaum, Halo Effect

- Method 48 persons approached in various public

buildings. Each was read a 400 word descripton of

a breaking and entering case, and asked How

likely do you think it is that he is guilty-

asked to rate guilt on an ordinal scale from 1

(definitely guilty) to 7 (definitely not guilty).

Four groups of 12 were read slightly different

scenarios - Group Guilt Level

- 1-Just the facts 4.00

- 2-told lawyer saw no reason to put D. on

stand 4.33 - 3-told D. testified but did not give any

important evidence, - and that D. has five prior convictions for

breaking and entering, - and two for possession of stolen goods. 3.25

- 4-same as above, but also with judges limiting

instruction 3.00

27

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- Study 2 Doob Kirshenbaum, Halo Effect

- Finding Halo Effect Learning something bad

about someone leads you to assume that other bad

things about them are true. (the two groups who

heard prior convictions both had higher ratings

of probable guilt). - Flaws (1)tiny sample size (2)no real basis for

comparison between the methodology of this study

and that of the courtroom- no trial, evidence,

voire dire, argument, witnesses, or deliberation.

28

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- Study 3 University of Chicago Research

- Method Jury Interviews.

- Finding Almost universal inability and/or

unwillingess among jurors to understand or

follow courts instruction on the use of prior

conviction evidence. It is almost universally

used to conclude that defendant was a bad man,

and thus guilty. - Flaws (1) No information about size of pool

observed or its representativeness (2) Vague

about exact numbers, methods, and operational

definitions (what were his criterea- how did he

find out whether or not the jury understood?)

29

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- Study 4 Columbia Journal of Law and Social

Problems - Method Random national survey of trial judges

and defense lawyers, asking whether they believed

jurors were able to follow limits of judges

instructions on the use of prior conviction

evidence. - Finding 98 of responding defense attorneys said

no, as did 43 of responding judges. - Flaws (1) Problem with reader-response polls- no

control over representativeness of the sample.

30

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- Study 5 Wissler Saks

- Method 160 Mock Jurors approached in public

places and private homes, given a .two-page case

summation and asked to determine guilt or

innocence. - Finding Jurors use prior conviction evidence to

help judge the likelihood of guilt in spite of

limiting instructions - -Higher conviction rate when prior conviction was

for murder as opposed to perjury, all else being

the same. - -No significant difference between mock jurors

rating of defendants credibility between cases

where prior history was introduced and when it

was not. - -Credibility NOT a function of prior conviction

evidence - -Conviction IS a function of prior conviction

evidence.

31

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- Study 5 Wissler Saks

- Flaws (1) Sample locations and size limited

only 20 people in group where prior history was

of murder - (2)Researchers admit one should be cautious in

generalizing from the results of this study to

jurors in a real trial- Dissent the obvious

explanation for why the Credibility of Defendant

did not change in participants eyes in spite of

changing prior conviction information is that

THERE WAS NO DEFENDANT. It is difficult to have

any feeling about the credibility of a

HYPOTHETICAL PERSON. Only a trial atmosphere can

properly reproduce the circumstances under which

a real juror must judge credibility.

32

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- Holding

- -There is an overwhelming probability that

prior conviction evidence introduced for the

purpose of impeachment will be considered as if

it had been introduced to show that the defendant

acted in conformity with his criminal past.

33

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- Revised Michigan Rule of Evidence 609

- -Prior conviction evidence allowed only if the

crime contained an element of dishonesty or false

statement, OR, an element of theft and was

punished with over a year in prison or death - AND probative value toward credibility

outweighs prejudicial effect. - -New Explicit Instructions on Weighing

- Probative Value ONLY consider age of conviction

and how indicative it is of veracity. - Prejudicial Effect ONLY consider prior

convictions similarity to current charge and

possible effects on decisional process if

admitting the evidence causes defendant to decide

not to testify. - Court must record its reasoning

34

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- Basis for Holding

- -We welcome the dissents critique of the methods

and conclusions of the studies we relied upon,

as social science experiments cannot serve as

the primary basis for judicial decision. Many

fundamental principles of our jurisprudence are

based on assumptions of human behavior that have

never been, and in most cases cannot be,

scientifically tested. - -Our modification of MRE 609 is the result of

assumptions about jury behavior and the

effectiveness of limiting instructions that were

accompanied by relatively little analysis or

study.

35

People v. Allen (Mich. 1988)

- We, therefore, in the words of the dissent,

act not on the basis of studies, but on the

common-sense premise that some prior

convictions are more probative than others, that

some are inherently more prejudicial, and that it

is absurd to suggest that jurors will be able to

avoid improper consideration of a defendants

criminal character once it has become known to

them. - -The Studies are merely relevant as SUPPORT, but

are not the BASIS of the decision.