Rational Engagement, Emotional Response, - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 54

Title:

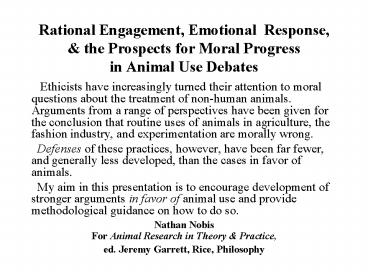

Rational Engagement, Emotional Response,

Description:

Rational Engagement, Emotional Response, & the Prospects for Moral Progress in Animal Use Debates Ethicists have increasingly turned their attention to moral ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:227

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Rational Engagement, Emotional Response,

1

Rational Engagement, Emotional Response, the

Prospects for Moral Progress in Animal Use

Debates

- Ethicists have increasingly turned their

attention to moral questions about the treatment

of non-human animals. Arguments from a range of

perspectives have been given for the conclusion

that routine uses of animals in agriculture, the

fashion industry, and experimentation are morally

wrong. - Defenses of these practices, however, have been

far fewer, and generally less developed, than the

cases in favor of animals. - My aim in this presentation is to encourage

development of stronger arguments in favor of

animal use and provide methodological guidance on

how to do so. - Nathan Nobis For Animal Research in Theory

Practice, - ed. Jeremy Garrett, Rice, Philosophy

2

Harms Moral Justification

- Many fields and occupations involve harming

animals, making them worse off. - Animals for our purposes, mammals birds

least controversial cases for discussion. - Typically, people in these fields will agree that

animals are being harmed. - They claim, however, that these harms are morally

justified not all harms are wrong, and these

harms arent wrong (indeed, perhaps some are

morally obligatory).

3

Common experimental procedures include

- drowning,

- suffocating,

- starving,

- burning,

- blinding,

- destroying their ability to hear,

- damaging their brains,

- severing their limbs,

- crushing their organs

- inducing

- heart attacks,

- cancers

- ulcers

- paralysis,

- Seizures

- forcing them to inhale tobacco smoke, drink

alcohol, and ingest various drugs, such as

heroine and cocaine.

4

A few commonly overlooked observations about harm

- (1) Painless killing can be (and often is)

harmful for the one who is killed it is bad for

him/her. - Why? They are deprived of whatever goods they

would have experienced. No interests can be

satisfied. - Thus, the common if painlessly killed, then

humane, so nothing morally objectionable views

need defense.

- (2) Recent ethological research shows that just

being in a laboratory, and undergoing routine

procedures, is stressful (and thus harmful) for

animals.

5

Balcombe JP, Barnard ND, Sandusky C, Laboratory

routines cause animal stress, Contemporary

Topics in Laboratory Animal Science, 2004, Nov,

43 (6)42-51

- Abstract Eighty published studies were appraised

to document the potential stress associated with

three routine laboratory procedures commonly

performed on animals handling, blood collection,

and orogastric gavage . . . - Significant changes in physiologic parameters

correlated with stress . . were associated with

all three procedures in multiple species in the

studies we examined. - The results of these studies demonstrated that

animals responded with rapid, pronounced, and

statistically significant elevations in

stress-related responses for each of the

procedures . . . - We interpret these findings to indicate that

laboratory routines are associated with stress,

and that animals do not readily habituate to

them. The data suggest that significant fear,

stress, and possibly distress are predictable

consequences of routine laboratory procedures,

and that these phenomena have substantial

scientific and humane implications for the use of

animals in laboratory research.

6

Balcombe JP, Laboratory environments and

rodents behavioural needs A review, Laboratory

Animals (in press)

- Abstract Laboratory housing conditions have

significant physiological and psychological

effects on rodents, raising both scientific and

humane concerns. Published studies of rats, mice

and other rodents were reviewed to document

behavioural and psychological problems

attributable to predominant laboratory housing

conditions. - Studies indicate that rats and mice value

opportunities to take cover, build nests,

explore, gain social contact, and exercise some

control over their social milieu, and that the

inability to satisfy these needs is physically

and psychologically detrimental, leading to

impaired brain development and behavioural

anomalies (e.g., stereotypies). To the extent

that space is a means to gain access to such

resources, spatial confinement likely exacerbates

these deficits. Adding environmental

enrichments to small cages reduces but does not

eliminate these problems, and I argue that

substantial changes in housing and husbandry

conditions would be needed to further reduce them.

7

Many ethicists have argued that its wrong to use

animals these ways theyve given reasons for

their views and defended them

- utilitarianism and other consequentialisms,

- rights-based deontologies,

- ideal contractarianisms (veil of ignorance,

Golden rule ethics), - virtue ethics,

- common-sense (least harm, needless harm)

moralities, - religious moralities, feminist ethics,

- and more indeed almost every major, influential

perspective in moral theory.

8

Even Kants, Rawls, and other moral theories

have been modified to be friendly to non-rational

moral patients (not moral agents)

- Improve the theory so there are direct duties to

baby ( other non-rational powerless humans

shes of moral value not because others care

about her, despite her not being a

moral agent, rational, etc.

9

If the theory is now not Bad for Baby (and other

vulnerable humans), it is now not Bad for

Animals?

10

Thus, an abundance of ethical resources in

defense of animals.

- However, this hasnt made much of a difference in

thought or deed regarding uses of animals. - Possible explanations

- big changes are always slow trickle-down is

slow - philosophers (and other thinkers and authors)

typically just arent very influential, - personal, financial, legal, political,

institutional barriers to doing the right thing, - ???

11

A competing explanation

- There are strong arguments that morally justify

(much of) the current treatment of animals. - Since these arguments are strong / sound / very

reasonable to accept, the defenses of animals are

weak / unsound / unreasonable. - Im going to suggest that this explanation is

unlikely, because these arguments are weak. - I encourage development of more and stronger

arguments in favor of, defending, animal use and

provide methodological guidance on doing so.

12

Emotional responses to moral issues

- It sometimes appears that the quality of our

thought on a topic is inversely proportional to

the intensity of our emotions concerning that

topic. - -- Fred Feldman, Confrontations With the Reaper

A Philosophical Study of the Nature and Value of

Death (Oxford, 1994).

13

Rational engagement of moral issues

- Identify some past instances of moral progress

in thought, attitude, deed - Hopefully, rational evaluation of arguments

contributed to this, somewhat! - We can identify some basic logical skills that

can help us improve the quality of our thought. - Apply these skills to some recent arguments

made by scientists and philosophers regarding

animals. - This is important because it seems that not

enough people consistently use these skills this

is not good.

14

Formerly controversial issues and simple

arguments

- Women shouldnt be allowed to go to university

because women are so emotional that abstract

thought is so difficult for them. - "Slavery is morally right because we slave-owners

benefit greatly from slavery." - "Since animals are not rational, it's morally ok

to raise them to be killed and eaten." - These are arguments what are their faults?

15

Women (1)

- Conclusion

- Women shouldnt be allowed to go to university.

- Why think that?

- Women are such emotional beings that abstract

thought is difficult for them. - Imprecise! SOME? or ALL?

- Some women are so emotional that abstract

thought is difficult. True, and true for some

men! - All women are so emotional False,

empirically indefensible claim, so unsound

argument

16

Women (2)

- Some women are so emotional that abstract

thought is difficult. True, and true for some

men! - Therefore, no women should be allowed to go to

university. - But how do you get from (1) to (2)? Whats the

missing linking premise? - A question How would some womens emotionality

justify restricting educational opportunities

from all women? Not clear.

17

Women (3)

- However, even if some or even all women are so

emotional and have difficulty with abstract

thought why would that justify denying any women

the opportunity to improve themselves through

education? - If my cup won't hold but a pint, and yours holds

a quart, wouldn't you be mean not to let me have

my little half measure full? - Sojourner Truth, Ain't I A Woman? 1851

18

Slavery

- "Slavery is morally right because we slave-owners

benefit greatly from slavery. - (1) Slave-owners benefit from slavery. True

- (C) Therefore, slavery is morally right. ?

- --------------------------------------------------

------------ - How do you get from (1) to (2)?

- Whats the missing, assumed linking premise?

- Slave-owners benefit from slavery. True

- If some group benefits from some arrangement,

then that arrangement is right. ? - Therefore, slavery is morally right.

19

Animals

- "Since animals are not rational, it's morally ok

to raise them to be killed and eaten. - Animals are not rational.

- Therefore, its OK to kill them

- Observations and questions

- (1) is imprecise some, or all, animals are not

rational? Which animals? - Ambiguity, lack of clarity what is meant by

rational? - Missing-link premise needed to make argument

logically valid If a being is not rational,

then its ok to kill it. False?

20

Logical skills The (moral) value of basic

predicate logic

- Attending to the intended meanings of unclear or

ambiguous words - what do you mean?

- animal, human, being human, human being,

person, human person, humanity - Precision regarding , quantity some, all?

- Assumed, unstated premises that link stated

reason(s) to conclusion. (Logical validity).

21

It seems these logical skills are generally

useful.

- A bioethicist disagrees about the value of these

skills for professional ethics - Frankly, science students would have very little

patience for the abstract argumentation and

reasoning that one finds in your paper and is

standard fare in philosophy journals.

22

Apply these ( other) logical skills to some

recent arguments

- Scientists

- Stuart Derbyshire, Ph.D., U Birmingham UK (used

to be at Pitt) pain researcher. - Mark Mattfield, Ph.D., Research Defense Society,

UK - Colin Blakemore, Ph.D., Medical Research Council,

UK - Adrian Morrison, Ph.D., DVM, U Penn, sleep

disorders

- Philosophers

- Carl Cohen

- Neil Levy, Cohen Kinds A Response to Nathan

Nobis, JoAP) - Tibor Machan, Putting Humans First

- Matthew Liao, Virtually All Human Beings as

Rightholders A Non-Speciesist Approach

23

The issue neednt be whether animals have

rights

- Moral or legal rights?

- Which moral rights? (be specific)

- Rights conflicts right to smoke, right to

a smoke-free environment - Rights appeals can conceal details.

- Common invalid argument

- If animals have rights, then serious change is

needed. But they dont have rights, so change

isnt needed. - Logically invalid conclusion doesnt follow

and avoids the concrete questions.

24

The issue neednt be whether animals have

rights

- Better to consider

- (1) whether various (specific) uses of animals

are morally permissible or not, whether any ways

of treatment are morally obligatory and - (2) why or why not.

- Keep this the focus on these deontic categories

is helpful for many practical and theoretical

reasons.

25

The issue also neednt be whether animals are

equal to humans

- Are any animals equal to humans? Are all humans

equal? Hard to answer - What is meant by equal? Not obvious.

- Which humans, which animals? (What is meant by

humans and animals?). (fetus, baby, adult,

100 y/o?) - Common invalid argument avoids the concrete

questions. - If animals are equal to humans, then serious

change is needed. But they arent equal, so

change isnt needed. - Equal consid. vs.No consid.vs. mid-level

consid? - Again, ideal Qs are about moral permissibility.

26

Objection An abundance of resources is a

philosophical embarrassment?

- Many philosophers argue that animals are treated

wrongly, but disagree on why (e.g., Peter Singer

demolishes Tom Regan and Regan demolishes

Singer). Therefore, there is no justification for

thinking that animals are treated wrongly. - Adrian Morrison Richard Vance, JAMA

27

A parallel argument

- Many thinkers argue that animals are not treated

wrongly, but disagree on why (e.g., Carl Cohen

demolishes Jan Narveson Narveson demolishes

Cohen). Therefore, there is no justification for

thinking that animals are not treated wrongly.

28

The false, unstated assumption

- If you believe p, and for reasons X, Y, Z, but

others believe p for reasons A, B, C, etc. and

these reasons are logically incompatible (and you

recognize this), then either you have no (good)

reason to believe p or there is no good reason to

believe p. - At the very least, this principle isnt one

typically accepted or universally applied (e.g.,

global warming is bad).

29

Appeals to evolution / biological perspectives

- Morrison to refrain from exploring nature in

every possible way would be an arrogant rejection

of evolutionary forces. - Evolution has endowed us with a need to know as

much as we can. (Nicoll, Russell). - Humans evolved therefore, morally we should .

Does not follow. - Constraints on using other humans to advance our

own genetic line, when its in our interest?

30

Benefits Arguments / Arguments from Necessity

- animal experiments are vital to the future

well-being of humans and, as long as they are

conducted to high ethical standards, they are

entirely justifiable. Mark Matfield - The argument Benefits for humans justify animal

experimentation (and other uses) - The are necessary.

31

Is animal use necessary? (1)

- Depends on what you mean by necessary.

- In one sense, yes!

- To do animal experiments, it is necessary to do

animal experiments. To make these exact

scientific discoveries using animals, it is

essential to use animals if animals werent

used, the experiments would be different.

32

Is animal use necessary? (2)

- In other senses, perhaps not. Is animal necessary

for making medical progress and for, more

generally, bettering human welfare? - Necessary for the well-being of humans, but

which humans? A few? (Maybe!). Everyone? Doubtful

that every human benefits from (every) animal

experiment. - There are other ways of bringing about goods for

humans - clinical research, epidemiology, in vitro

research, uses of technology, autopsies,

prevention, etc. - feeding people, getting existing medical care to

them, etc.. Its been argued that these would

yield greater human utility.

33

Defenses of the low (human) utility of animal

experimentation

- RC Greek N Shanks, Animal Research in Light of

Science (2006? Rodopi) - N Shanks LaFollette, Brute Science (Routledge

1997) - RC Greek J Greek DVM, Sacred Cows Golden

Geese (Continuum 2000), Specious Science (2002),

What Will We Do if We Dont Experiment on

Animals? (2004) - They argue that other methods of research are

more effective at addressing human needs.

34

Benefits argument

- Animal experiment yields some benefits.

- If some action benefits someone (or some group),

then that action is right. false needs

refinement and serious defense - Therefore, animal experimentation (and other

uses) are right. - What about direct harms (to animals, to humans,

esp. indirect harms from opportunity costs)? How

are these weighed? A careful methodology would be

nice, at least is necessary for serious defense.

35

Want benefits?

- Whatever benefits animal experimentation is

thought to hold in store for us, those very same

benefits could be obtained through experimenting

on humans esp. vulnerable ones instead of

animals. Indeed, given that problems exist

because scientists must extrapolate from animal

models to humans, one might think there are good

scientific reasons for preferring human

subjects. - Philosopher Ray Frey

36

Why not use these humans?Blakemores answer

- The only firm line to make moral distinctions

on genetic and morphological grounds is between

our own species and other species. - Suggested if something is of our species, then

it is more morally valuable than any animals. - But he says a human embryo, certainly before the

nervous system begins to develop, is just a

bundle of cells. - Suggested being of our species does not

necessarily confer moral value. - We should have a special attitude toward other

humans, so crucial to this argument is how we

define a person. He did not do this.

37

Why not use these humans?Derbyshires answer

- Animals lack the capacity for reflection (and

therefore an inner world) and the capacity for

reasoning (So do many humans!!) - Its remarkable that we have to consider the

question. - Not remarkable if someone suggests that whats

required for a presumption against harm are

properties that many, many human beings lack. - Society cares about vulnerable humans.

- All of them? What about secret experiments? What

if they could be re-educated? Why do they care?

(Harms)

38

Avoiding objections from non-rational human

beings.

- A common claim

- Its wrong to seriously harm a being only if that

being is rational, autonomous, makes moral

choices, is creative, intelligent, contributes to

society, etc. - OK, animals arent like that, but neither are

lots of (conscious, feeling) humans. This

principle suggests its not seriously wrong to

harm them. Is this principle correct?

39

Some odd inferencesCohen, Levy Kinds

- Cohen NEJM Moral rights depend on moral

agency, the ability to respond to moral claims.

A being has rights only if its a of a kind

characterized by moral agency. - Finnis to be a person is to belong to a kind of

being characterized by rational (self-conscious,

intelligent) nature. - Scanlon the class of beings whom it is possible

to wrong will include at least all those beings

who are of a kind that is normally capable of

judgment-sensitive attitudes.

40

Cohen, Levy Kinds

- Cohen All humans are of a kind capable of moral

agency, but - animals are not beings of a kind capable of

exercising or responding to moral claims. Animals

therefore have no rights, and they can have

none. - What kind are animals? How are humans who are not

moral agents of the kind moral agent? Cohen

doesnt explain.

41

Cohens possible answer?

- Humans who are non-moral agents are of this kind

because they are members of a set e.g., the

kind, a species some of which are moral agents.

- Response But animals are also members of a set

e.g., the kind, sentient beings some of whom

are moral agents also! They have rights too, on

Cohens account! - Humans and animals are of many kinds, some

overlapping, some not. Inconsistent conclusions

follow from Cohen-esque reasoning.

42

Levys attempt to find the right kind the

narrowest natural kind

- If (1) an individual A is a member of some

species S and (2) some, most or all of the other

members of that species have some property C and

(3), on the basis of having property C, they have

moral property R, then individual A has moral

property R as well, even though A lacks property

C.

43

If (1) an individual A is a member of some

species S and (2) some, most or all of the other

members of that species have some property C and

(3), on the basis of having property C, they have

moral property R, then individual A has moral

property R as well, even though A lacks property

C.

- C non-moral property of "having doneno serious

crimes - R "not deserving lifeimprisonment."

- Implications for lone criminal?

- C "intelligent" and "aware

- R "being such that one ought to be allowed to

make decisions to direct one's own life." - Implications for young children and others?

44

Machans Arguments from Whats Normal

- A being has moral rights (presumably making it

wrong to harm it) only if it a moral nature, a

capacity to see the difference between right

and wrong and choose accordingly. - It is this moral capacity that establishes a

basis for rights, not the fact that animals, like

us, have interests or can feel pain. - Humans are of the kind of being that have such

a moral nature and animals are not thus humans

have rights and animals do not.

45

What about humans who seem to lack this moral

capacity?

- We must consider humans as they exist normally,

not abnormally and focus on the healthy cases,

not the special or exceptional or borderline

ones. - We do need to deal with borderline cases. But we

can do so only by applying and adapting the

knowledge we acquire from the normal case. We

cant start with the exception and infer the

rule.

46

The suggested argument

- Humans who lack moral capacities are human.T!

- If someone is human, then they have all the

(moral) properties that normal, healthy,

typical humans have. - Therefore, these humans have moral capacities,

and so they have rights. - Reply 2 is, at least, unsupported, and is an

instance of a generally false principle for moral

non-moral properties. (e.g., 4 limbs Ted Bundy)

47

Matthew Liao, Virtually All Human Beings as

Rightholders The Species-Norm Account

- to be a rightholder (a being with the highest

moral status), something need not - be a moral agent

- have the potential to be a moral agent

- be of the kind (species) that normally is a moral

agent - be actually sentient, conscious, etc. or even

have the potential, i.e., that its possible in

some sense - Could be tinkered into a pro-animal exper. view.

48

The correct answer is

- A being has rights iff the entity has

incorporated into it the genetic basis for the

species capacity for moral agency (i.e. the

relevant bits of DNA that normally allow for

moral agency) or the functional equivalent

thereof (e.g. software and/or hardware that would

normally allow for moral agency in an artificial

being). The intrinsic value that resides in the

relevant genetic bits grounds rightholding even

when that genetic material is blocked from

developing and cannot allow for moral agency. - If X is like that, then X has moral rights.

49

Liaos reasoning in favor of the view, it seems

- There are moral duties only if there are moral

agents. T - There are moral agents only if there are beings

with the genetic basis for moral agency. OK

accept this for sake of argument - Therefore, there are moral duties only if there

are beings with the genetic basis for moral

agency. - Therefore (?), any being with the genetic basis

for moral agency is a rightholder.

50

A parallel argument

- There are moral duties only if there are living

beings, or beings that can perceive, or . T - There are living beings, or beings that can

perceive only if there are beings with the

genetic basis for life, perception, etc. OK - Therefore, there are moral duties only if there

are beings with the genetic basis for life,

perception, etc. - Therefore (?), any being with the genetic basis

for life, perception, is a rightholder.

51

Objections from Chris Grau, FIU

- If the species-norm account is true, then

- A cabbage that has "integrated" the relevant

genetic bits but is damaged such that the

capacity for moral agency is permanently blocked.

(this cabbage has rights even though it lacks

moral agency and the potential for it.) - A (future) computer with the relevant hardware.

software "integrated" but blocked. This computer

has rights even though it would lack both moral

agency and the potential for moral agency. - Cabbage or computer vs. sentient animals and

sentient humans lacking the relevant genetic

material for moral agency? - The species norm account seems entirely ad hoc.

52

Conclusions / Summary

- Presented a basic method for thinking about moral

issues demonstrated its use applied it to some

recent arguments defending current animal use

and/or criticizing pro-animal arguments. - Suggested that these arguments are weak.

- My hope since these methods are generally

useful, perhaps future defenders of current uses

of animals will utilize them for better

arguments. - To make moral progress and contribute to

reasonable debate it is important that this is

done.

53

For an overview of the recent literature on

ethics and animals issues, see Angus Taylors

Ethics Animals An Overview of the

Philosophical Debate (Broadview, 2003). For

arguments from utilitarianism, see, among other

sources, Peter Singers Practical Ethics, 2nd

Edition (Cambridge UP, 1993) and his Animal

Liberation, 3rd Edition (Harper, 2001) although

the former is, strictly speaking, not an argument

from utilitarianism. From rights-based

deontology, see, among other sources, Tom Regans

The Case for Animal Rights, 2nd Edition (U

California Press, 2004), as well as his more

accessible Empty Cages Facing the Challenge of

Animal Rights (Rowman Littlefield, 2004) for

Rawlsian-style ideal contractarianism, see among

other sources, Mark Rowlands Animals Like Us

(Verso, 2002) from virtue ethics, see among

other sources, Rosalind Hursthouses Ethics,

Humans and Other Animals (Routledge, 2000), from

common-sense morality, see, among other sources,

Mark Bernsteins Without a Tear Our Tragic

Relationship With Animals (U Illinois Press,

2004) and David DeGrazias Animal Rights A Very

Short Introduction (Oxford, 2002) for religious

moralities, see, among other sources, Matthew

Scullys Dominion The Power of Man, the

Suffering of Animals, and the Call to Mercy (St.

Martins, 2003) from feminism, see Carol Adams

and Josephine Donavan (eds.) Beyond Animal

Rights A Feminist Caring Ethic for the Treatment

of Animals (Continuum, 1996).

54

Stuart Derbyshire,an animal experimentation

advocate

- It is not possible to advocate animal welfare

and at the same time give animals untested drugs

or diseases, or slice them open to test a new

surgical procedure. . . - The Scientist, 3/06, Time to Abandon the Three

Rs - Submitting to refinement, reduction, and

replacement risks the future of animal research

- Once the perspective of the animal is adopted,

it is inevitable that all experimentation will be

seen negatively, as no animal experiments are in

the interest of the animal - - Why Animals Rights Are Wrong (p. 39)