Benchmarking WebBased Education: A Quality Improvement Model - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 1

Title:

Benchmarking WebBased Education: A Quality Improvement Model

Description:

... UMDNJ School of Health-Related Professions (SHRP) mirrors the national picture. ... Intended learning outcomes are reviewed regularly to ensure clarity, utility, ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:51

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Benchmarking WebBased Education: A Quality Improvement Model

1

Benchmarking Web-Based Education A Quality

Improvement Model

Craig L. Scanlan EdD, RRT, FAARC

Background and Need Current estimates are that

about 85 of all universities and colleges and

offer distance education courses, up from 62

since 1998.1 It is estimated that between 1998

and 2002, distance education enrollments will

have quadrupled, from 500,000 to over two million

students.2 Most of this growth is attributed to

the dramatic upsurge in Web-based education. As

often occurs with educational innovation, the

cart is preceding the horse. Heretofore, the

rapid growth in Web-based education has yet to be

matched with the application of sound quality

assessment strategies. The situation at the UMDNJ

School of Health-Related Professions (SHRP)

mirrors the national picture. SHRP has been

offering Web-based education since 1997, with the

number of courses growing exponentially each

year. Although individual course evaluation has

always been applied, no overall assessment of the

Schools distance learning program had ever taken

place, nor was there a strategy to do so. To that

end, the UMDNJ-SHRP Technology Task Force (TTF)

was charged with evaluating the Schools overall

distance learning program.

Data Sources and Collection For each benchmark,

one or more of four key data sources were

identified as applicable for assessing

performance levels (1) SHRP students enrolled in

Spring 2002 Web courses, (2) faculty teaching

Spring 2002 Web courses, (3) Academic Computing

Services (ACS) staff, and (4) the SHRP Office of

Enrollment ease of Services (OES). Student data

were gathered via an online survey questionnaire,

faculty data by a semi-structured group interview

(focus group), and ACS and OES information via

staff interviews and/or records review.

Results The benchmarking model selected by the

TTF has proved to be a significant source of

quality improvement data that is already being

applied to enhance SHRPs online education

programming. Based on the preliminary benchmark

review process alone, the need for (1) separate

approval guidelines for Web-based courses, (2)

revision of the Schools course evaluation form,

and (3) a Program- or Department-level CQI

framework for online courses have all been

established. Analysis of student and

faculty-provided data corroborate these findings

and are providing clear and specific direction in

terms of both curriculum and faculty development

needs. General issues of regarding student

services and technical support have also been

highlighted.

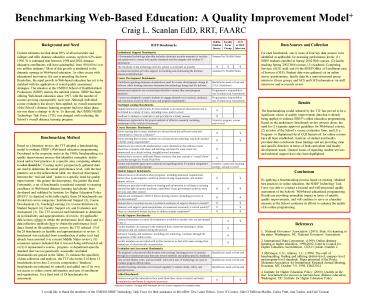

Benchmarking Method Based on a literature

review, the TTF adopted a benchmarking model to

evaluate SHRPs Web-based education programming.

Developed in the corporate sector in the 1980s,

benchmarking is a quality improvement process

that identifies exemplary institu-tional and/or

best practices in a specific area, comparing what

is to what should be.3 Existing and/or

prospectively gathered data are used to determine

the actual performance level, with the best

practices set as the achievement ideal. An

observed discrepancy between the real and ideal

points to a specific need for quality improvement

- the greater the discrepancy, the greater the

need. Fortunately, a set of benchmarks considered

essential to ensuring excellence in Web-based

distance learning had already been developed and

validated by Institute for Higher Education

Policy (IHEP).4 As depicted in the table (right),

these 24 benchmarks are divided into seven

categories Institutional Support (3), Course

Development (3), Teaching/Learning (3), Course

Structure (4), Student Support (4), Faculty

Support (4), and Evaluation and Assessment (3).

The TTF reviewed each benchmark to determine its

(a) feasibility and appropriateness of review

(b) applicable data sources (where to obtain the

performance level data) and (c) data collection

methods (how to obtain the performance level

data). Based on this preliminary review, the TTF

selected 13 of the 24 benchmarks as feasible and

appropriateness to review. A benchmark was

excluded from consideration if either (a) it had

already been assessed (via a recent Middle States

review) (b) consensus opinion indicated that it

was not being addressed at all, or (b) it

represented a course-, program- or

department-specific standard that was not

generically assessable (excluded benchmarks are

grayed in the Table). To enhance the specificity

of data collection and analysis, the TTF also

broke 2 of these 13 benchmarks down into 2 or

more components (breakout benchmarks are

indicated by asterisk) and added one of its own

(on access to online course information and ease

of enrollment and registration), for a final

total of 18 benchmarks for assessment.

Conclusions By applying a benchmarking process

based on existing validated best practices in

online education, the SHRP Technology Task Force

was able to conduct a focused and well-structured

quality assessment of the Schools Web-based

educational programming. Results are providing

immediate impact in terms of specific quality

improvements, and will continue to serve as a

baseline measure as the School continues its

efforts to enhance the quality of its online

programming.

References 1. National Governors Association.

(2001). State of e-learning in the states.

Washington, DC. National Governors

Association. 2. International Data Corporation.

(1999). Online distance learning in higher

education, 1998-2002. Cited in Council for Higher

Education Accreditation, CHEA Update, Number 2.

3. McGregor, E.N., Attinasi, L.C. (1998). The

craft of benchmarking finding and utilizing

district-level, campus- level, and program-level

standards, Paper presented at the Rocky Mountain

Association for Institutional Research Annual

Meeting, Bozeman, MT, October 7-9, 1998.

ED423014 4. Institute for Higher Education

Policy. (2000). Quality on the line benchmarks

for success in Internet-base distance education.

Washington, DC Institute for Higher Education

Policy.

Indicates a breakout of a single IHEP

benchmark into two or more components for

evaluative clarity

I would like to thank the members of the

UMDNJ-SHRP Technology Task Force for their

assistance in this effort Drs. Laura Nelson,

Joyce OConnor, Julie OSullivan-Maillet, Carlos

Pratt, Ann Tucker, and Gail Tuzman