Chapter 3 Differential Equations - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 57

Title:

Chapter 3 Differential Equations

Description:

Chapter 3 Differential Equations 3.1 Introduction Almost all the elementary and numerous advanced parts of theoretical physics are formulated in terms of differential ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:393

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Chapter 3 Differential Equations

1

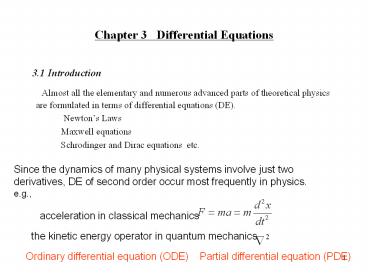

Chapter 3 Differential Equations

- 3.1 Introduction

- Almost all the elementary and numerous

advanced parts of theoretical physics are

formulated in terms of differential equations

(DE). - Newtons Laws

- Maxwell equations

- Schrodinger and Dirac equations

etc.

Since the dynamics of many physical systems

involve just two derivatives, DE of second order

occur most frequently in physics. e.g.,

acceleration in classical mechanics

the kinetic energy operator in quantum mechanics

Ordinary differential equation (ODE) Partial

differential equation (PDE)

2

Examples of PDEs

- 1. Laplace's eq.

- This very common and important eq. occurs

in studies of - a. electromagnetic phenomena, b.

hydrodynamics, - c. heat flow,

d. gravitation. - 2. Poisson's eq.,

- In contrast to the homogeneous Laplace eq.,

Poisson's eq. is non-homogeneous with a

source term

3. The wave (Helmholtz) and time-independent

diffusion eqs., . These

eqs. appear in such diverse phenomena as

a. elastic waves in solids, b. sound or

acoustics, c. electromagnetic waves,

d. nuclear reactors. 4. The

time-dependent diffusion eq.

3

- 5. The time-dependent wave eq.,

- where is a four-dimensional analog of

the Laplacian. - 6.The scalar potential eq.,

- 7.The Klein-Gordon eq., ,

and the corresponding vector eqs. in which ? is

replaced by a vector function. - 8.The Schrodinger wave eq.

- and

- for the time-independent case.

4

Some general techniques for solving second-order

PDEs

1.Separation of variables, where the PDE is split

into ODEs that are related by common constants

which appear as eigenvalues of linear operators,

LY lY, usually in variable. 2. Conversion of

a PDE into an integral eq. using Green's

functions applies to inhomogeneous PDEs. 3.

Other analytical methods such as the use of

integral transforms. 4. Numerical calculations

Nonlinear PDEs Notice that the above mentioned

PDEs are linear (in ?). Nonlinear ODEs an PDEs

are a rapidly growing and important field. The

simplest nonlinear wave eq

Perhaps the best known nonlinear eq. of second is

the Korteweg-deVries (KdV) eq.

5

3.2 First-order Differential Equations

We consider here the general form of first-order

DE

(3.1)

The eq. is clearly a first-order ODE. It may or

may not be linear, although we shall treat the

linear case explicitly later.

Separable variables

Frequently, the above eq. will have the special

form

6

or P(x)dx Q(y) dy

0 Integrating from (x0, y0) to (x, y) yields,

Since the lower limits and contribute

constants, we may ignore the lower limits of

integration and simply add a constant of

integration.

Example Boyle's Law In differential form

Boyle's gas law is

V-volume, P - Pressure. or

ln V ln P C. If we set C ln k, PV k.

7

Exact Differential Equations

Consider

P(x,y) dx Q(x,y) dy 0 . This eq. is said to

be exact if we match the LHS of it to a

differential dj,

Since the RHS is zero, we look for an unknown

function ? j(x,y) const. and dj? 0.

We have

and

The necessary and sufficient for our eq. to be

exact is that the second, mixed partial

derivatives of j (????assumed continuous) are

independent of the order of differential

If such j(x,y) exists then the solution is

j(x,y)C.

8

There always exists at least one integrating

facts, a(x,y), such that

Linear First-order ODE

If f (x,y) has the form -p(x)y q(x), then

(3.2)

It is the most general linear first-order ODE. If

q(x) 0, Eq.(3.2) is homogeneous (in y). A

nonzero q(x) may represent a source or deriving

term. The equation is linear each term is linear

in y or dy/dx. There are no higher powers that

is, y2, and no products, ydy/dx. This eq. may be

solved exactly.

9

Let us look for an integrating factor a(x) so

that

(3.3)

may be rewritten as

(3.4)

The purpose of this is to make the left hand

side of Eq.(3.2) a derivative so that it can be

integratedby inspection. Expanding Eq. (3.4),

we obtain

Comparison with Eq.(3.3) shows that we must

require

10

Here is a differential equation for a(x) , with

the variables a and x separable. We separate

variables, integrate, and obtain

(3.5)

as our integrating factor.

With a(x) known we proceed to integrate

Eq.(3.4). This, of course, was the point of

introducing a(x) in the first place. We have

Now integrating by inspection, we have

The constants from a constant lower limit of

integration are lumped into the constant C.

Dividing

by a(x) , we obtain

11

Finally, substituting in Eq.(3.5) for a yields

(3.6)

Equation (3.6) is the complete general solution

of the linear, first-order differential

equation, Eq.(3.2). The portion

corresponds to the case q(x) 0 and

is a general solution of the Homogeneous

differential equation. The other term in

Eq.(3.6),

is a particular solution corresponding to the

specific source term q(x) .

12

V

Example RL Circuit For a

resistance-inductance circuit Kirchhoffs law

leads to

for the current I(t) , where L is the

inductance and R the resistance, both constant.

V(t) is the time-dependent impressed voltage.

From Eq.(3.5) our integrating factor a(t) is

13

Then by Eq.(3.6)

with the constant C to be determined by an

initial condition (a boundary condition).

For the special case V(t)V0 , a constant,

If the initial condition is I(0) 0, then

and

14

3.3 SEPARATION OF VARIABLES

A very important PDE in physics

Electromagnetic field, wave transition etc.

Cartesian coordinates Cylindrical

coordinates Spherical coordinates

m mass of an electron hbar Plank constant

15

- Certain partial differential equations can be

solved by separation of variables. The method

splits the partial differential equation of n

variables into ordinary differential equations.

Each separation introduces an arbitrary constant

of separation . If we have n variables, we have

to introduce n-1 constants, determined by the

conditions imposed in the problem being solved. - Using for the Laplacian. For the

present let be a constant.

Cartesian Coordinates In Cartesian

coordinates the Helmholtz equation becomes

(3.7)

16

Let

(3.7a)

Dividing by

and rearranging terms, we obtain

(3.8)

The left-hand side is a function of x alone,

whereas the right-hand side depends only on y

and z, but x , y , and z are all independent

coordinates. The only possibility is setting each

side equal to a constant, a constant of

separation. We choose

(3.10)

(3.9)

Rearrange Eq.3.10

where a second separation constant has been

introduced.

17

Similarly

(3.11)

(3.12)

introducing a constant by

to produce a symmetric set of

equations. Now we have three ordinary

differential equations ((3.9),(3.11), and (3.12))

to replace Eq.(3.7). Our solution should be

labeled according to the choice of our constants

l, m ,and n ,that is ,

(3.13)

- Subject to the conditions of the problem being

solved. - We may develop the most general solution of

Eq.(3.7)by taking a linear combination of

solutions ,

(3.14)

Where the constant coefficients are

determined by the boundary conditions

18

Example Laplace equation in rectangular

coordinates

z

Consider a rectangle box with dimensions (a,b,c)

in the (x,y,z) directions. All surfaces of the

box are kept at zero potential, except the

surface zc, which is at a potential V(x,y). It

is required to find the potential everywhere

inside the box.

zc

yc

y

xa

x

19

Example Laplace equation in rectangular

coordinates

Where

Then the solutions of the three ordinary

differential equations are

20

To have F0 at xa and yb, we must have aanp,

and bbmp. Then

Since FV(x,y) at zc

We have the coefficients

Here the features of Fourier series have been

used.

21

Circular Cylindrical Coordinates

- With our unknown function ? dependent on ?, f ,

and z , the Helmholtz equation becomes

(3.15)

or

(3.16)

As before, we assume a factored form for ? ,

(3.17)

22

Substituting into Eq.(3.16), we have

(3.18)

All the partial derivatives have become ordinary

derivatives. Dividing by PFZ and moving the z

derivative to the right-hand side yields

(3.19)

Then

(3.20)

And

(3.21)

23

Setting , multiplying by ,

and rearranging terms, we obtain

(3.22)

We may set the right-hand side to m2 and

(3.23)

Finally, for the ? dependence we have

(3.24)

This is Bessels differential equation . The

solution and their properties are presented in

Chapter 6. -

The original Helmholtz equation has been replaced

by three ordinary differential equations. A

solution of the Helmholtz equation is

A general Sol.

(3.26)

24

Spherical Polar Coordinates

Let us try to separate the Helmholtz equation in

spherical polar coordinates

(3.27)

(3.29)

(3.30)

25

- we use as the separation constant. Any

constant will do, but this one will make life a

little easier. Then

(3.31)

and

(3.32)

Multiplying Eq.(3.32) by and rearranging

terms, we obtain

(3.33)

26

Again, the variables are separated. We equate

each side to a constant Q and finally obtain

- Once more we have replaced a partial

differential equation of three variables by three

ordinary differential equations. Eq.(3.34) is

identified as the associated Legendre equation in

which the constant Q becomes l(l1) l is an

integer. If is a (positive) constant, Eq.

(3.35) becomes the spherical Bessel equation. - Again, our most general solution may be

written

(3.34)

(3.35)

(3.36)

27

The restriction that k2 be a constant is

necessarily. The separation process will Still be

possible for k2 as general as

In the hydrogen atom problem, one of the most

important examples of the Schrodinger Wave

equation with a closed form solution is k2f(r)

Finally, as an illustration of how the constant m

in Eq.(3.31) is restricted, we note that f in

cylindrical and spherical polar coordinates is an

azimuth angle. If this is a classical problem, we

shall certainly require that the azimuthal

solution F(f) be singled valued, that is,

28

This is equivalent to requiring the azimuthal

solution to have a period of 2p or some integral

multiple of it. Therefore m must be an integer.

Which integer it is depends on the details of the

problem. Whenever a coordinate corresponds to an

axis of translation or to an azimuth angle the

separated equation always has the form

29

3.4 Singular Points

Let us consider a general second order

homogeneous DE (in y) as y'' P(x) y' Q(x) y

0 (3.40)

where y' dy/dx. Now, if P(x) and Q(x) remain

finite at x , point x is an ordinary

point. However, if either P(x) or Q(x) ( or both)

diverges as x ?approaches to , is a

singular point.

Using Eq.(3.40), we are able to distinguish

between two kinds of singular points

30

These definitions hold for all finite values of

x0. The analysis of is similar to

the treatment of functions of a complex variable.

We set x 1/z, substitute into the DE, and then

let . By changing variables in the

derivative, we have

(3.41)

(3.42)

Using these results, we transform Eq.(3.40) into

(3.43)

The behavior at x ? (z 0) then depends on the

behavior of the new coefficients

31

and

as z? 0. If these two expressions remain finite,

point x ? is an ordinary point. If they

diverge no more rapidly than that 1/z and 1/ ,

respectively, x is a regular singular point,

otherwise an irregular singular point.

Example

Bessel's eq. is

Comparing it with Eq. (3.40) we have

P(x) 1/x, Q(x) 1 - ,

which shows that point x 0 is a regular

singularity. As x ?? ? (z ?? 0), from Eq.

(3.43), we have the coefficients

and

Since the Q(z) diverges as , point x ? is

an irregular or essential singularity.

32

We list , in Table 3.4, several typical ODEs and

their singular points.

Table 3.4

Equation

Irregular singularity

- Hypergeometric

___

0,1,

2. Legendre

___

-1,1,

3. Chebyshev

___

-1,1,

4. Confluent hypergeometric

5. Bessel

6. Laguerre

7. Simple harmonic oscillator

___

___

8. Hermite

33

3.5 Series Solutions

(A)

(B)

The Bessels function

A linear second-order homogeneous ODE

y'' P(x) y' Q(x) y 0.

34

Linear second-order ODE

- In this section, we develop a method of a

series expansion for obtaining one solution of

the linear, second-order, homogeneous DE. - A linear, second-order, homogeneous ODE may

be written in the form - y'' P(x) y' Q(x) y 0.

- the most general solution may be written

as - Our physical problem may lead to a

nonhomogeneous, linear, second-order DE - y'' P(x) y' Q(x) y F(x).

- Specific solution of this eq., yp, could be

obtained by some special techniques. Obviously,

we may add to yp any solution of the

corresponding homogeneous eq.

Hence,

The constants c1 and c2 will eventually be

fixed by boundary conditions

35

To seek a solution with the form

Fuchss Theorem We can always get at least one

power-series solution, provided we are expanding

about a point that is an ordinary point or at

worst a regular singular point.

36

- .

- To illustrate the series solution, we apply

the method to two important DEs. - First, the linear oscillator eq.

- , (3.44)

- with known solutions y sin wx, cos wx.

- We try

with k and al? still undetermined. Note that k

need not be an integer. By differentiating twice,

we obtain

37

By substituting into Eq. (3.44), we have

(3.45)

- From the uniqueness of power series the

coefficients of each power of x on the LHS must

vanish individually. - The lowest power is , for l? 0 in

the first summation. The requirement that the

coefficient vanishes yields - k(k-1) 0.

- Since, by definition, a0 ? 0, we have

- k(k-1) 0

- This eq., coming from the coefficient of the

lowest power of x, is called the indicial

equation. The indicial eq. and its roots are of

critical importance to our analysis. k0 or

k1 - If k 1, the coefficient (k1)k of

must vanish so that - 0.

- We set ?l j2 in the first summation

and ?l' j in the second. This results in

38

2 (kj2)(kj1) 0

or

- This is a two-term recurrence relation.

We first try the solution k 0. The recurrence

relation becomes

which leads to

39

So our solution is

If we choose the indicial eq. root k 1, the

recurrence relation becomes

Again, we have

For this choice, k 1, we obtain

40

- This series substitution, known as

Frobenius' method, has given us two series

solution of the linear oscillation eq. However,

two points must be strongly emphasized - (1) The series solution should be

substituted back into the DE, to see if it works. - (2) The acceptability of a series

solution depends on its convergence (including

asymptotic convergence). - Expansion above

- It is perfectly possible to write

Indeed, for the Legendre eq the choice x0 1

has some advantages. The point x0 should not

be chosen at an essential singularity -or the

method will probably fail.

41

- Limitations of Series Approach

- This attack on the linear oscillator eq. was

perhaps a bit too easy. - To get some idea of what can happen we try

to solve Bessel's eq. -

(3.46) - Again, assuming a solution of the form

42

- we differentiate and substitute into Eq.

(3.46). The result is - By setting? l? 0, we get the coefficient of

, - a0k(k-1) k- 0.

- The indicial equation

- with solution k n or -n. For the

coefficients of x(k1), we obtain - For k n or -n (k is not equal 1/2),

does not vanish and we must require 0. - Proceeding to the coefficient of for k

n, we set ?l j in the 1st, 2nd, and 4th

terms and ?l j-2 in the 3rd term. By requiring

the resultant

coefficient of to vanish, we obtain

(nj)(nj-1)(nj)- 0.

43

When j? j2, this can be written for j0 as

(3.47)

which is the desired recurrence relation.

Repeated application of this recurrence relation

leads to

, and so on, and in general

Inserting these coefficients in our assumed

series solution, we have

44

In summation form

(3.48)

- The final summation is identified as the

Bessel function Jn(x). - When k -n and n is not integer, we may

generate a second distinct series to be labeled

J-n(x). However, when -n is a negative integer,

trouble develops. - The second solution simply reproduces the

first. We have failed to construct a second

independent solutions for Bessel's eq. by this

series technique when n is an integer.

45

Will this method always work? The answer is

no! SUMMARY

- If we are expanding about an ordinary point

or at worst about a regular singularity, the

series substitution approach will yield at least

one solution (Fuchss theorem). - Whether we get one or two distinct

solutions depends on the roots of the indicial

equation. - 1. If the two roots of the indicial

equation are equal, we can obtain only one

solution by this series substitution method. - 2. If the two roots differ by a

non-integer number, two independent solutions

may be obtained. - 3. If the two roots differ by an

integer, the larger of the two will yield a

solution.

- The smaller may or may not give a solution,

depending on the behavior of the coefficients. In

the linear oscillator equation we obtain two

solutions for Bessels equation, only one

solution.

46

- Regular and Irregular Singularities

- The success of the series substitution

method depends on the roots of the indicial eq.

and the degree of singularity. To have clear

understanding on this point, consider four simple

eqs.

(3.49a)

(3.49b)

(3.49c)

(3.49d)

47

For the 1st eq., the indicial eq. is

k(k-1) - 6 0,

- giving k 3, -2. Since the eq. is

homogeneous in x ( counting as

), here is no recurrence relation. However, we

are left with two perfectly good solution,

and . - For the 2nd eq., we have -6 0, with no

solution at all, for we have agreed that ? 0.

The series substitution broke down at Eq. (3.49b)

which has an irregular singular point at the

origin. - Continuing with the Eq. (3.49c), we have

added a term y'/x. The indicial eq. is

, but again, there is no recurrence

relation. The solutions are - y , both perfectly acceptable

one term series. - For Eq. (3.49d), (y'/x? y'/x2), the

indicial eq. becomes k 0. There is a recurrence

relation

48

Unless a is selected to make the series terminate

we have

Hence our series solution diverges for all x ?0.

49

3.6 A Second Solution

- In this section we develop two methods

of obtaining a second independent solution an

integral method and a power series containing a

logarithmic term. First, however we consider the

question of independence of a set of function. - Linear Independence of Solutions

- Given a set of functions, ??, the

criterion for linear dependence is the existence

of a relation of the form -

-

(3.50) - in which not all the coefficients k are

zero. On the other hand, if the only solution of

Eq. (3.50) is k0 for all ?, the set of functions

??is said to be linearly independent. - Let us assume that the functions ?? are

differentiable. Then, differentiating Eq. (3.50)

repeatedly, we generate a set of eq.

50

This gives us a set of homogeneous linear eqs. in

which k? are the unknown quantities. There is a

solution kl? ?0 only if the determinant of the

coefficients of the k?'s vanishes,

.

51

- This determinant is called the Wronskian.

- 1. If the wronskian is not equal to zero,

then Eq.(3.50) has no solution other than k? 0.

The set of functions is therefore independent. - 2. If the Wronskian vanishes at isolated

values of the argument, this does not necessarily

prove linear dependence (unless the set of

functions has only two functions). However, if

the Wronskian is zero over the entire range of

the variable. the functions ?? are linearly

dependent over this range. - Example Linear Independence

- The solution of the linear oscillator eq.

are

. The Wronskian becomes - and f1 and f2 are therefore linearly

independent. For just two functions this means

that one is not a multiple of the other, which is

obviously true in this case.

52

- You know that

but this is not a linear relation.

Example Linear Dependence

Consider the solutions of the one-dimensional

diffusion eq. .

We have ?f1 ex and f2 e-x, and we add ?3

cosh x, also a solution. Then

because the first and third rows are identical.

Here, they are linearly dependent, and indeed,

we have - 2 coshx 0 with kl? ? 0.

53

- A Second Solution

- Returning to our 2nd order ODE

- y'' P(x) y' Q(x) y 0

- Let y1 and y2 be two independent solutions.

Then Wroskian is - W .

- By differentiating the Wronskian, we obtain

In the special case that P(x) 0,

i.e. y'' Q(x) y 0,

(3.52)

W constant.

54

- Since our original eq. is homogeneous, we

may multiply solutions and by whatever

constants we wish and arrange to have W 1 ( or

-1). This case P(x) 0, appears more frequently

than might be expected. ( in Cartesian

coordinates, the radical dependence of (r?)

in spherical polar coordinates lack a first

derivative). Finally, every linear 2nd-order ODE

can be transformed into an eq. of the form of

Eq.(3.52). - For the general case, let us now assume

that we have one solution by a series

substitution ( or by guessing). We now proceed to

develop a 2nd, independent solution for which W ?

0.

We integrate from x1 a to x1 x to obtain

(3.53)

55

(3.54)

By combining Eqs. (3.53) and (3.54), we have

(3.55)

Finally, by integrating Eq. (3.55) from x2b to

x2x we get

Here a and b are arbitrary constants and a term

y1(x)y2(b)/y1(b) has been dropped, for it leads

to nothing new. As mentioned before, we can set

W(a) 1 and write

56

(3.56)

If we have the important special case of P(x)

0. The above eq. reduces to

Now, we can take one known solution and by

integrating can generate a second independent

solution.

Example A Second

Solution for the Linear Oscillator eq.

From y 0 with P(x) 0, let

one solution be y1 sin x.

57

Chapter 4. Orthogonal Functions (Optional

Reading)

- 4.1 Hermitian Operators (HO)

- HO in quantum mechanics (QM)

- As we know, is an HO

operator. As is customary in QM, we simply assume

that the wave functions satisfy appropriate

boundary conditions vanishing sufficiently

strongly at infinity or having periodic behavior.

The operator L is called Hermitian if - The adjoint A of an operator A is defined

by - Clearly if A A (self-adjoint) and

satisfies the above mentioned boundary

conditions, then A is Hermitian. The expectation

value of an operator L is defined as