4. The Text of the Bible - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

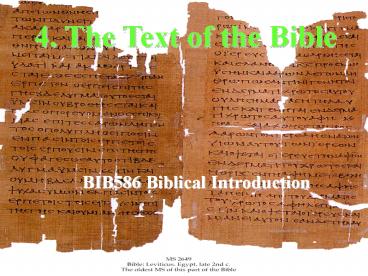

Title: 4. The Text of the Bible

1

4. The Text of the Bible

- BIB586 Biblical Introduction

2

4. The Text of the Old Testament

- 3.1 Proto-Masoretic Masoretic Texts

- 3.2 Pre-Samaritan Samaritan Pentateuch

- 3.3 Septuagint

- 3.4 Targumim

- 3.5 Peshitta

- 3.5 Vulgate

3

3.0 Introduction

- R. Ishmael "My son, be careful, because your

work is the work of heaven should you omit

(even) one letter or add (even) one letter, the

whole world would be destroyed" b. Sot. 20a

4

3.0 Introduction

- There are many witnesses to the Old Testament

(First Testament). The Hebrew is the easiest to

deal with, while the translations are dealt with

in a secondary manner, due to the problem of

retroversion. - Until the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls,

however the earliest Hebrew witness to the

Scriptures were the Nash Papyri (1st-2nd century

CE).

5

3.0 Introduction

- "Interest in the text of the Bible began in the

first centuries of the common era when learned

church fathers compared the text of the Hebrew

Bible and different Greek versions. In the third

century Origen prepared a six-column edition

(hence its name Hexapla) of the Hebrew Bible,

which contained the Hebrew text, its

transliteration into Greek characters, and four

different Greek versions. Likewise, Jerome

included in his commentaries various notes

comparing words in the Hebrew text and their

renderings in Greek and Latin translations."

Tov, Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible, 16

6

3.1 Proto-Masoretic Masoretic Texts

- "The name Masoretic Text refers to a group of

manuscripts and other sources all of which are

close to each other. Many of the elements of

these manuscripts and even their final form were

determined in the early Middle Ages, but they

continue a much earlier tradition. The name

Masoretic Text was given to this group because of

the apparatus of the Masorah attached to it. This

apparatus, which was added to the consonantal

base, developed from earlier traditions in the

seventh to the eleventh centuries the main

developments occurring in the beginning of the

tenth century with the activity of the Ben Asher

family in Tiberias. Tov, Textual Criticism of

the Hebrew Bible, 16

7

3.1 Proto-Masoretic Masoretic Texts

- "The received consonantal text preceded the one

that includes the vocalization and accents. Both

of these circulated in many slightly deviating

forms, and were finally stabilized only with the

advent of the printed Rabbinic Bible toward the

end of the 15th century. However, earlier forms

of the MT come close to such a stabilization.

The earliest attestations of the consonantal

framework of the MT-found in many, but not all,

Qumran texts - date to around 250 BC. Their

resemblance (especially 1QIsab) to the medieval

form of the MT is striking, showing how accurate

the transmission of the MT was through the ages.

These earliest attestations are called

proto-Masoretic since their consonantal

framework formed the basis for the later

Masoretic mss. Tov, "Text Criticism (OT), ABD

8

3.1 Proto-Masoretic Masoretic Texts

- The Masoretic Text (MT) Contains

- The consonantal text found in the proto-Masoretic

texts of the Second Temple era and the Masorah

which developed later - The vocalization developed by the Masoretes

- Para-textual elements

- Accentuation

- The apparatus of the Masorah

9

3.1.1 The Consonantal Text

- The MT probably developed from the Pharisees (?),

with possible Temple ties. - The History of the Consonantal Text of the MT

- 1. The period of internal differences in the

textual transmission. - This period comes to an end at the time of

destruction of the Second Temple. - N.B. the Qumran material contains not only

proto-Masoretic texts, but also pre-Samaritan,

Hebrew source for the LXX, Qumran original, and a

"non-aligned"

10

3.1.1 The Consonantal Text

- The differences in the proto-Masoretic group and

the later MT tended to be limited to single words

and phrases. - "Talmudic and later rabbinic literature have

preserved other early variants. Still other

early variants are found in the Masoretic

madinh9a)e4 and ma(arba)e4 readings and in the

Masoretic handbook Minh9at Shay." Tov

11

3.1.1 The Consonantal Text

- 2. The Period of relatively high degree of

textual consistency. - From the destruction of the Second Temple until

the 8th century CE. - Documents from the Judean Desert (Wad4

Murabba(at and Nah9al H9ever ) written before the

Bar-Kochba rebellion (132-135 CE) . . . Cairo

Genizah material. - "Non-Hebrew sources from this period include the

Greek translations by Kaige-Theodotion, Aquila,

and Symmachus, the Aramaic Targums, and the

Vulgate." Tov

12

3.1.1 The Consonantal Text

- "All textual evidence preserved from the second

period reflects MT, but this fact does not

necessarily imply the superiority of that textual

tradition. The communities which fostered other

textual traditions either ceased to exist (the

Qumran) or dissociated themselves from Judaism

(the Samaritans and Christians)." Tov

13

3.1.1 The Consonantal Text

- 3. The Period of almost complete textual unity.

- From the 8th century until the end of the Middle

Ages. - "The earliest dated Masoretic mss proper are from

the 9th century, and are characterized by the

introduction of vocalization, cantillation signs,

and the Masorah. The consonantal texts of the

individual codices are virtually identical." Tov

14

3.1.2 Vocalization

- "Vocalization and accents were added to the

consonantal text of MT at a relatively late

stage. This additional layer of information is

known only from the MT, but is similar to the

tradition of reading the Sam. Pent. During the

Middle Ages the Samaritans developed a system of

vocalization, but the mss of the Sam. Pent.

remain without systematic vocalization." - Qumran used vowel letters matres lectionis

- "The purpose of vocalization was to solidify the

reading of the text in a fixed written form on

the basis of the oral tradition which had been

stable in antiquity. As with all other

15

3.1.2 Vocalization

- forms of reading (vocalization), the Masoretic

system reflects the exegesis of the Masoretes,

although the greater part of it is based on

earlier traditions." Tov - Three Systems of Vocalization

- Tiberian (North-Palestinian)

- Palestinian (South-Palestinian) vowel signs are

placed above the consonants - Babylonian subdivided into simple and compound

vowel signs are placed above the consonants.

16

3.1.2 Vocalization

- "In the circles that occupied themselves with the

vocalization of the biblical text from the 8th to

the 10th century AD in Tiberias, the most

prominent families were those of Ben-Asher and

Ben-Naphtali. The Ben-Asher system was later

accepted universally, while that of Ben-Naphtali

came into disuse. It is not known whether any of

the transmitted mss offer a purely Ben-Naphtali

tradition hence not all details about this

system of vocalization are known, even though one

learns much from the variants between it and

Ben-Asher." Tov

17

3.1.2 Vocalization

- N.B. Moshe Goshen-Gottstein's discussion of the

Ben Asher witness - Second Rabbinic Bible eclectic text (BH1-2)

- codex Leningrad B 19a (AD 1009) (BH3-BHS)

- But, the Aleppo Codex is considered the best

(Hebrew University Library Project)

18

3.1.3 Para-Textual Elements

- "Once it became unacceptable to make any more

changes to the biblical text, the earliest

generations of the sope6rm directed their

activities toward accurately recording all the

peculiarities in their mss." Tov - 1. Paragraph Divisions

- "With painstaking care the Masoretes transmitted

the division of the text into paragraphs (Heb

pa4ra4sa, pl. pa4ra4siyyot), which resembled

the system now also attested in most Qumran

texts. They distinguished between small textual

units separated from each other by open spaces

between verses within the line (pa4ra4sa

se6tuma, closed section, indicated with the

letter samek), and

19

3.1.3 Para-Textual Elements

- larger textual units separated from each other by

spaces that leave the whole remaining line blank

(pa4ra4sa pe6tuh9a, open section, indicated

with the letter pe). The Masoretes also

indirectly indicated versification (with the

silluq accent), following an ancient tradition

indicated (by spaces) in a few Qumran texts

(1QLev, 4QDan a, c) and in several Greek texts

such as 8H9evXll." Tov - 2. Inverted Nun

- Num 10.35-36 and Ps 107.23-28, 40 (x7?)

- Thus it is stated in Sifre on Numbers (section

84) "the section wrah snb yhyw is naqud (dotted)

before it and after it because this is not its

place.

20

3.1.3 Para-Textual Elements

- The opinion of Rabbi is that it forms a book

itself." Israel Yeivin, Introduction to the

Tiberian Masorah, 46 - "That the Inverted Nun indicate here a

dislocation of the text is also attested by the

Septuagint. In the recension form which this

Version was made, verses 35, 36 preceded verse

34, so that the order of the verses in question

is Numb X. 35, 36, 34 and this seems to be the

proper place for the two verses." C. D.

Ginsburg, Introduction to the Massoretico-Critical

Edition of the Hebrew Bible, 343

21

3.1.3 Para-Textual Elements

- 3. Extraordinary Points (Puncta Extraordinaria)

- "Supralinear (occasionally in combination with

infralinear) points are found in fifteen places

in the OT (e.g., Gen 334 Ps 2713). While

these points originated from scribal notations

indicating that the elements thus highlighted

should be deleted (a convention used in many

Qumran texts), within the Masoretic corpus these

symbols were reappropriated to indicate doubtful

letters ." Tov

22

3.1.3 Para-Textual Elements

- 'Abot R. Nat. "The words "unto us and to our

children" (Deut 29.28) are dotted. Why is that? .

. . This is what Ezra said If Elijah comes and

says to me, "Why did you write in this fashion?"

And if he says to me, "You have written well," I

shall remove the dots from them. - De Lagarde used these dots as the bases to argue

that all MT manuscripts were copied from a single

source.

23

3.1.3 Para-Textual Elements

- 4. Suspended Letters (Litterae Suspensae)

- "In the mss some letters are intentionally placed

higher than those around them (i.e.,

superscripted between surrounding letters). A

good example is the suspended nun in Judg 1830,

where the text with the nun is read mnsh

(Manasseh) or without the nun as msh (Moses).

As in the Qumran texts, the suspended letters

indicate later additions, which nevertheless were

transmitted as such in the MT ." Tov

24

3.1.3 Para-Textual Elements

- 5. Special Letters

- "The special form of some letters directs the

readers attention to details that were important

for the Masoretes, such as the middle letter or

word in a book. For a littera minuscule see Gen

24 for a littera majuscule, see Lev 1333. In

other instances imperfectly written letters are

indicated especially. " Tov

25

3.1.3 Para-Textual Elements

- 6. Ketib-Qere

- "In a large number of instances ranging from

848 to 1566 according to the different traditions

the Masorah parva (smaller Masorah) notes that

one should disregard the written text (Aramaic

ketib, "what is written") and read instead a

different word or words (Aramaic qere, "what

is read")." Tov - "Opinions vary about whether the Qere represents

a Masoretic correction, a textual variant, or

something else."

26

3.1.3 Para-Textual Elements

- "Opinions vary about whether the Qere represents

a Masoretic correction, a textual variant, or

something else." Tov - "Initially, the Qere was intended as a

correction, particularly to discourage blasphemy,

such as the Qere perpetuum (the constant Qere) of

the written Tetragrammaton (YHWH) to be read as

)a6do4na4y. Subsequently, the already existing

system of incorporating corrections as marginal

notes was also used to preserve for posterity

deviant/variant readings. Still later, all these

marginal notes came to be (mis)understood as

corrections. Recently, Barr (1981) suggested

that the Qere words originated in the reading

tradition because there is never more than one

Qere word." Tov

27

3.1.3 Para-Textual Elements

- "The second group of notations associated with

the Masorah parva is indicated by the notation

se6brn, followed by an almost identical word

(e.g., mmnw/mmnh in Judg 1134). The se6brn

notations closely resemble those of the Qere

indeed, various words indicated as Qere in some

mss are indicated as se6brn in others. The

term is an abbreviation of se6brn

we6ma(tn, i.e., one might think (sbr) that x

should be read instead of y, but that is a wrong

assumption (ma(tn)." Tov

28

3.1.3 Para-Textual Elements

- "Third, the Masorah parva mentions some 250

consonantal variants between Palestinian

(ma(arba4)e, or western) and Babylonian

(ma4dnh9a4)e, or eastern) readings." Tov

29

3.1.3 Para-Textual Elements

- 7. Corrections of the Scribes (Tiqqune

sope6rm) - "The term refers to words (18 or 11 depending on

the sources the oldest source is the Mekilta on

Exod 157) that tradition says were changed by

the sope6rm e.g., my wickedness (Num 1115

MT) replaced an original reading your

wickedness. All supposed emendations concern

minor changes in words that the sope6rm deemed

inappropriate for God or (in one instance) Moses

(Num 1212). In some sources these corrections

are called kinnuye sope6rm (euphemisms of

the scribes), implying

30

3.1.3 Para-Textual Elements

- that the sope6rm had a different understanding

of these words without, however, changing the

text itself. Many details in the list of

tiqqunm are dubious. Nevertheless, it is

considered likely that theological alterations

have been made in the text, even though the

specific tiqqune6 sope6rm which have been

transmitted may not give the best examples of

this process" Tov

31

3.1.4 Accentuation

- "The accents, also named cantillation signs,

which add an exegetical layer and musical

dimension to the consonants and vowels, have

three different functions - 1. To direct the biblical reading in the

synagogue with musical guidelines - 2. To denote the stress in the word

- 3. To denote the syntactical relation between the

words as either disjunctive or conjunctive" Tov

32

3.1.5 The Apparatus of the Masorah

- "The Masorah in the narrow and technical sense of

the word refers to an apparatus of instructions

for the writing of the biblical text and its

reading. This apparatus was prepared by

generations of Masoretes and was written around

the text. The purpose of this apparatus was to

ensure that special care would be exercised in

the transmission of the text." Tov

33

3.1.5 The Apparatus of the Masorah

- Two main parts to the Masorah

- 1. Masorah parva Mp written as Aramaic notes

in the side margins of the text. Includes - The number of specific occurrences of spellings

or vocalizations. - The Qere, Sebirin, and all para-textual

notations. - Special details like shortest verse or the middle

verse in the Torah, etc.

34

3.1.5 The Apparatus of the Masorah

- 2. Masorah magna Mm written as Aramaic notes

in the upper or lower margins of the text. - "This apparatus is closely connected with the Mp

as its function is to list in detail the

particulars mentioned by way of allusion in the

Mp, especially the verses referred to by the

apparatus." Tov

35

3.1.5 The Apparatus of the Masorah

- Some Editions of the Masorah

- C. D. Ginsburg, The Massorah Compiled from

Manuscripts, Alphabetically and Lexically

Arranged, vols. I-IV (London/Vienna, 1880-1905

repr. Jerusalem 1971) - G. E. Weil, Massorah Gedolah manuscrit B.19a de

Leningrad, vol. I (Rome, 1971). - D. S. Loewinger, Massorah Magna of the Aleppo

Codex (Jerusalem, 1977).

36

3.1.6 MT Manuscripts

- Qumran, Murabba'at, Masada

- Nash Papyrus (Exod 20.2-17, partly Deut 5.6-21)

- Geniza fragments

- Ben Asher Manuscripts

- Codex Cairensis (Former Latter Prophets, 895

CE) - Aleppo Codex (Shelomo ben Buya'a wrote the

consonants, while Aaron Ben Asher vocalized and

accentuated the codex, 925 CE) lost Gen

1.1-Deut 28.26 SoS 3.12-the end, i.e., Qoheleth,

Lamentation, Esther, Daniel, and Ezra.

37

3.1.6 MT Manuscripts

- Ben Asher Manuscripts

- A Tenth-century codex from the Karaite synagogue

in Cairo containing the Pentateuch. - Codex Leningrad B 19A (from 1009)

- Codex B.M. Or. 4445, indicated as B (significant

sections of the Torah from the first half of the

tenth century) - Codex Sassoon 507 of the Torah (tenth century)

- Codex Sassoon 1053 of the Bible (tenth century)

38

3.1.6 MT Manuscripts

- Printed Editions

- "Earliest editions included portions (all with

Rabbinic commentary and to some extent with

Targum), e.g. Psalms, 1477 (Bologna?), Prophets,

1485/86 (Soncino), Writings, 1486/87 (Naples),

Pentateuch, 1491 (Lisbon), etc. and complete

Bibles, e.g., Soncino, 1488, Naples, 1491/93,

Brescia, 1494. The first Rabbinic Bible was

edited by Felix Pratensis and was also published

by Daniel Bomberg in 1516/17, a considerable

critical achievement with in large measure served

as a basis for the second Rabbinic

39

3.1.6 MT Manuscripts

- Printed Editions

- Bible of Jacob ben Chayyim." Würthwein, The Text

of the Old Testament, 37 - The Second Rabbinic Bible of Jacob ben Chayyim

(published by Daniel Bomberg in Venice, 1524/25) - Hebrew texts Targum comments by Rashi, Ibn

Ezra, Kimchi, etc. - 925 leaves in four folio volumes index

- However this was an eclectic text, therefore not

the best ben Asher representation.

40

3.1.6 MT Manuscripts

- Printed Editions

- "Particularly important for the advance in

biblical research have been the so-called

polyglots, multilingual editions that give the

text of the Bible in parallel columns in Hebrew

(MT and Sam. Pent.), Greek, Aramaic, Syriac,

Latin, and Arabic, accompanied by Latin

translations and introduced by grammars and

lexicons. The first is the Complutensian

Polyglot (1514-17), prepared by Cardinal Ximenes

in Alcala (Latin Complutum). The second was

published in Antwerp (1569-72), the third in

Paris (1629-45), and the fourth, the most

extensive, in London (1654-57), edited by B.

Walton and E. Castell." Tov

41

3.1.6 MT Manuscripts

- Printed Editions

- Johann Heinrich Michaelis (1720)

- Benjamin Kennicott Vetus Testamentum Hebraicum

cum variis lectionibus, 2 vol. (Oxford,

1776-1780) 600 mss, 52 editions of the Hebrew

text and 16 mss of the Samaritan. - J. B. de Rossi collected variants 1,475

manuscripts and editions. - S. Baer Franz Delitzsch (1869ff.) not

completed

42

3.1.6 MT Manuscripts

- Printed Editions

- C. D. Ginsburg (British Foreign Bible Society,

1908ff. 1926) Jacob ben Chayyim text. - Norman H. Snaith (British Foreign Bible

Society, 1958) Ms. Or. 2626-2628. - BH1-2 used the Jacob ben Chayyim text.

- BH3 and BHS have used the Codex Leningrad B 19A

- Hebrew University Bible (HUB) using the Aleppo

text.

43

The First Edition of the Psalter, 1477 Bologna,

with David Kimhi

44

Complutensian Polyglot (1514-17)

45

Codex Cairensis 827CE, Moshe ben Asher

46

Aleppo Codex Shelomo ben Buya(a, 930CE

47

Aleppo Codex Shelomo ben Buya(a, 930CE

48

Codex 17, Firkowitsch Collection 930CE

49

Codex Leningrad B19A 1008-9CE

50

Codex Leningrad B19A 1008-9CE

51

Benjamin Kennicott Vetus Testamentum Hebraicum

cum variis lectionibus, 2 vol. (Oxford, 1776-1780)

52

Kennicott

53

Benjamin Kennicott Vetus Testamentum Hebraicum

cum variis lectionibus, 2 vol. (Oxford, 1776-1780)

54

Benjamin Kennicott Vetus Testamentum Hebraicum

cum variis lectionibus, 2 vol. (Oxford, 1776-1780)

55

3.2 Pre-Samaritan Samaritan Pentateuch

- "The Samaritan Pentateuch contains the text of

the Torah, written in a special version of the

"early" Hebrew script as preserved for centuries

by the Samaritan community. This text is

permeated with ideological elements which,

however, form only a thin layer added to the

text. Scholars are divided in their opinion on

the date of this version, but it was probably

based on an early, pre-Samaritan, text, similar

to those found in Qumran." Tov

56

3.2 Pre-Samaritan Samaritan Pentateuch

- 3.2.1 Origin Background

- "The Samaritans themselves believe that the

origin of their community goes back to the time

of Eli (11th century BC), when the Jews

withdrew from Shechem to establish a new cult in

Shiloh, which was later brought to Jerusalem.

According to this conception, the Jews split off

from the Samaritans, not the other way around. A

different view is reflected in 2 Kgs 1724-34,

according to which the Samaritans were not

originally Jews, but pagans brought to Samaria by

the Assyrians after the fall of Samaria in the

8th century BC. In accordance with this

tradition, in the Talmud the Samaritans were

indeed named Kythians (cf. 2 Kgs 1724). " Tov

57

3.2 Pre-Samaritan Samaritan Pentateuch

- 3.2.2 Character of the Samaritan Pentateuch

- ". . . it differs from MT in some six thousand

instances. While it is true that a great number

of these variant are merely orthographic, and

many others are trivial and do not affect the

meaning of the text, yet it is significant that

in about 1,900 instances SP agrees with LXX

against MT." Würthwein, 42-43

58

3.2 Pre-Samaritan Samaritan Pentateuch

- 1. Harmonizing Alterations

- "The Sam. Pent. contains various kinds of

harmonizing alterations, especially additions (to

one passage on the basis of another one) that, by

definition, are secondary. These alterations

appear inconsistently (i.e., features which have

been harmonized in one place have been left in

others). The Sam. Pent. was not sensitive to

differences between parallel laws within the

Pentateuch, which, as a rule, have remained

intact, while differences between parallel

narrative accounts, especially in the speeches in

the first chapters of Deuteronomy and their

sources, were closely scrutinized." Tov

59

3.2 Pre-Samaritan Samaritan Pentateuch

- "Thus, in the MT the Fourth Commandment in Exod

208 begins with za4kor (remember) and in

Deut 512 with sa4mor (observe), but the Sam.

Pent. reads sa4mor in both verses. " Tov - ". . . parallel verses from Deut 19-18 are added

in Exodus (after 1824 and within v 25),

resulting in a double account of the story of

Moses appointing of the judges." - Addition of details

60

3.2 Pre-Samaritan Samaritan Pentateuch

- 2. Linguistic Corrections this is found in both

the Pre-Samaritan and SP in general. - 3. Sectarian Changes in the Samaritan Pentateuch

- "This concerns the most important doctrinal

difference between the Jews and the Samaritans

the central place of worship (Jerusalem for the

Jews, Mount Gerizim for the Samaritans)." Tov - ". . . the Samaritans added a commandment to the

Decalog (after Exod 2014 and Deut 518) that

secured the centrality of Mount Gerizim in the

cult. This commandment is

61

3.2 Pre-Samaritan Samaritan Pentateuch

- composed of a series of biblical pericopes that

mention such a central cult in Shechem (Deut

1129a 272b, 3a, 4-7 1130 in this

sequence). The addition of this material as the

Tenth Commandment was made possible by changing

the First Commandment into an introductory

clause." Tov - ". . . various alterations in Deuteronomy where

the characteristic expression the place which

the Lord your God will choose is changed to the

place which the Lord your God has chosen (e.g.,

Deut 1210, 11).

62

3.2 Pre-Samaritan Samaritan Pentateuch

- From the Samaritan perspective, Shechem was

already the chosen place in the time of Abraham,

whereas from the historical perspective of

Deuteronomy, the choice of Gods place

(Jerusalem) yet lay in the future, after the

conquest of the land and the election of David."

Tov - 4. Orthography in the SP

- The use of matres lectionis

- 5. Pre-Samaritan Texts

- "There are large harmonizing additions from

Deuteronomy in Exodus and Numbers

63

3.2 Pre-Samaritan Samaritan Pentateuch

- (and in one case, vice versa), well attested in

4QpaleoExm, 4Q158, 4Q364 (both biblical

paraphrases), 4QNumb, 4QDeutn, and 4Q175

(Test)." Tov - 6. Modern Editions of the SP

- A. F. von Gall, Der hebräische Pentateuch der

Samaritaner, (Giessen, 1914-18 repr. Berlin,

1966). - A R. Sadaqa, Jewish and Samaritan Version of

the Pentateuch - With Particular Stress on the

Differences between Both Texts, (Tel Aviv,

1961-65).

64

Samaritan Pentateuch 1215/6 - Num 34.26-35.8

65

A. F. von Gall, Der hebräische Pentateuch der

Samaritaner, (Giessen, 1914-18 repr. Berlin,

1966)

66

3.3 Septuagint

- "LXX is a Jewish translation which was made

mainly in Alexandria. Its Hebrew source differed

greatly from the other textual witnesses (MT, T,

S, V and many of the Qumran texts), and this

accounts for its great significance in biblical

studies. Moreover, LXX is important as a source

for early exegesis, and this translation also

forms the basis for many elements in the NT."

Tov

67

3.3 Septuagint

- Date "According to the generally accepted

explanation of the testimony of the Epistle of

Aristeas, the translation of the Torah was

carried out in Egypt in the third century BCE.

This assumption is compatible with the early date

of several papyrus and leather fragments of the

Torah from Qumran and Egypt, some of which have

been ascribed to the middle or end of the second

century BCE (4QLXXLeva, 4QLXXNum, Pap. Pouad 266,

Pap. Pylands Gk. 458)." Tov

68

3.3 Septuagint

- Witnesses

- 1. Early texts written on papyrus and leather

including both scrolls and codices. - 2nd Century BCE onward, many fragments in

Palestine Egypt. - Chester Beatty / Scheide Collection (Egypt, 1931)

contained most of the books, even Daniel. - Also Qumran 4QLXXLeva

- 2. Uncial (uncialis) or majuscule (majusculus)

manuscripts from the fourth century onwards,

written with "capital" letters. - 3. Minuscule (minusculus) or cursive manuscripts,

written with small letters, from medieval times.

69

3.3 Septuagint

- Witnesses

- 2. Uncial (uncialis) or majuscule (majusculus)

manuscripts from the fourth century onwards,

written with "capital" letters. - B Vaticanus, dates from the 4th century and is

considered the best complete manuscript of the

LXX. Relatively free of corruption and influences

of the revisions of LXX. - S or a Sinaiticus, dates from the 4th century

and usually agrees with B, when the two reflect

the Old Greek translation, but S

70

3.3 Septuagint

- Witnesses

- is influenced by the later revisions of the LXX.

- A Alexandrinus dates from the 5th century and

is greatly influenced by the Hexaplaric tradtion

and in several books represents it faithfully. - 3. Minuscule (minusculus) or cursive manuscripts,

written with small letters, from medieval times.

71

Codex Vaticanus LXX, - B Cod. Vat. Gr. 1209

72

3.3 Septuagint

- Witnesses

- 3. Minuscule (minusculus) or cursive

manuscripts, written with small letters, from

medieval times. - Many minuscule manuscripts from the ninth to the

sixteenth centuries are known. N.B. Göttingen and

Cambridge editions.

73

3.3 Septuagint

- Critical Editions

- 1. A. E. Brooke, N. McLean and H. St. J.

Thackeray, The Old Testament in Greek according

to the Text of Codex Vaticannus (Cambridge,

1906-1940) known as "The Cambridge Septuagint". - Gen-Neh, Esther, Judith, Tobit according to B,

and where that manuscript is lacking, ti has been

supplemented by A or S.

74

"The Cambridge Septuagint"

75

3.3 Septuagint

- Critical Editions

- 2. Ziegler, ed., Göttingen Septuaginta, Vetus

Testamentum Graecum auctoritate Societatis

Litterarum Göttingensis editum. - This is the most precise and thorough critical

edition of the LXX.

76

Göttingen Septuaginta

77

3.3 Septuagint

- Importance of LXX for Biblical Studies

- Gen genealogies, chronological data

- Exod the second account of the building of the

Tabernacle in chapters 35-40 - Num sequence differences, pluses and minuses of

verses - Josh significant transpositions, pluses, and

minuses - Sam-Kgs many major and minor differences,

including pluses, minuses, and transpositions,

involving different chronological and editorial

structures

78

3.3 Septuagint

- Jer differences in sequence, much shorter text

- Eze slightly shorter text

- Pro differences in sequence, different text

- Dan Est completely different text, including

the addition of large sections, treated as

"apocryphal." - Chr "synoptic" variants, that is, readings in

the Greek translation of Chronicles agreeing with

MT in the parallel texts.

79

3.3.1 Revisions of the Septuagint

- General

- LXX and the revisions share a common textual

basis. - The revision corrects the LXX in a certain

direction. - Kaige-Theodotion

- The Greek scroll of the Minor Prophets found in

Nahal Hever was identified as an early kaige

revision of the LXX by Barthelemy (1952). - Also in 6th column of the Hexapla and in the

Quinta (fifth) column of the Hexapla . . . .

80

3.3.1 Revisions of the Septuagint

- Kaige-Theodotion

- Supplanted the current Greek version of the Book

of Daniel . . . ." Jellicoe, The Septuagint and

Modern Study, 84 - Corrected the LXX with a Hebrew text.

- Aquila

- Aquila prepared his revision in approximately 125

CE. Some biblical books have two different

editions. - Student of R. Akiba

- "Aquila . . . Made an attempt to represent

accurately every word, particle, and even

81

3.3.1 Revisions of the Septuagint

- Aquila

- morpheme. For example, he translated the nota

accusativi ta separately with su,n, "with,"

apparently on the basis of the other meaning of

ta, namely "with"." Tov - The Aquila Onqelos theory.

- Symmacus

- 2nd or 3rd century CE either an Samaritan who

had become a proselyte or and Jewish-Christian

Ebionite. - "Two diametrically opposed tendencies are

82

3.3.1 Revisions of the Septuagint

- Symmacus

- visible in Symmachus's revision. On the one hand

he was very precise, while on the other hand, he

very often translated ad sensum rather

representing the Hebrew words with stereotyped

renderings." Tov - Hexapla

- Origen in the mid-3rd century CE.

- Six columns

- Obelos (?) elements in Greek, but not in Hebrew

83

3.3.1 Revisions of the Septuagint

- Hexapla

- Asteriskos (?) extant in Hebrew, but not in

Greek, which were added in the fifth column from

one of the other columns. - Post-Hexaplaric Revisions

- Lucian (d. 312 CE). (b, o, c2, e2 in the

Cambridge Septuagint). - Known from both Greek and Latin sources, now in

Hebrew (4QSama).

84

3.4 Peshitta

- Peshitta means "the simple translation or

plain" - "Peshitta is of Christian or Jewish-Christian

origin. - "The quality of the Peshitta (Syriac translation)

varies from book to book, ranging from fairly

accurate to paraphrastic. The Heb Vorlage of the

Peshitta was more or less identical with MT. The

Peshitta offers fewer variants than the LXX, but

more than the Targums and the Vulgate." Tov

85

3.5 Targumim

- Targum means explanation, commentary or

translation. - Both Jewish and Samaritan Targumim exist. However

the Jewish Targumim had a higher status within

their own community. - Jewish Targumim exist for all the books of the

Hebrew Bible except Ezra, Nehemiah and Daniel. - The Targumim reflect a Hebrew text that is very

close to the MT, except for the Job Targum from

Qumran.

86

3.5 Targumim

- Targum Onqelos (Torah)

- Translated by Onqelos the proselyte, "under the

guidance of R. Eliezer and R. Joshua" - Date first, third or fifth century CE?

- As a rule Onqelos follows the plain sense of

Scripture, but in the poetical sections it

contains many exegetical elements. - Sperber argues that there are 650 minor variants

in the Targum Onqelos.

87

3.5 Targumim

- Palestinian Targumim (Torah)

- Jerusalem Targum I Targum Pseudo-Johnathan.

- Jerusalem Targum II, III The Fragment(ary)

Targum(im) - Targumim from the Cairo Genizah

- Vatican Neophyti 1 discovered in 1956 in a

manuscript dating 1504 1st/2nd century CE but

others 4th/5th century CE.

88

3.5 Targumim

- Targum to the Prophets

- Targum Jonathan to the Prophets varies from book

to book. - Targum to the Hagiographa

89

3.5 Targumim

- "The quality of the translation of the Aramaic

Targums varies from Targum to Targum and from

book to book (see especially Komlosh 1973). As a

rule, the Targums from Palestine are more

paraphrastic in character than the Babylonian

ones. The more literal translations of 11QtgJob

and 4QtgLev, though found in Palestine, are an

exception to this rule." Tov

90

3.5 Targumim

- "The Targums usually reflect the MT deviations

from it are based mainly on exegetical

traditions, not on deviating texts. An exception

must be made for 11QtgJob, which contains

interesting variants and which possibly lacks

some verses of the MT (4212-17), a fact which

would be significant for the literary criticism

of the book. It may perhaps be assumed that

other Targums in an earlier stage of their

development also contained more variants than in

their present form. Targum Onqelos as a rule

contains more variants than the Palestinian

Targums." Tov

91

3.6 Vulgate

- "Though occasionally reflecting variants, this

Latin translation almost always reproduces MT."

Tov

92

3.2 The Text of the Second Testament

- 3.2.1 The Text of the N.T.

- 3.2.2 N.T. Text Criticism

93

3.2.1.1 Greek Manuscripts General

- "Greek mss of the NT, now numbering more than

5,300, customarily have been characterized in

three differing ways (1) by the material upon

which they are written (papyrus, parchment, or

paper) (2) by their calligraphic type (uncial or

minuscule handwriting) and (3) by the function

of the document containing the text

(continuous-text ms, lectionary, or patristic

quotation). The traditional way of listing them,

however, cuts across these categories (utilizing

one or two from each) and follows the scheme of

papyri, uncials, minuscules, lectionaries, and

patristic quotations." Eldon Jay Epp, "Textual

Criticism (NT)," ABD

94

3.2.1.1 Greek Manuscripts General

- Statistics (as of 1989)

- Papyri Catalogued (96)

- Uncial MSS Catalogued (299)

- Minuscule MSS Catalogued (2,812)

- Lectionaries Catalogued (2,281)

- Total (5,488)

- Metzger, The Text of the New Testament Its

Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 262

95

3.2.1.2 Transmission

- 1. What is Required? ". . . knowledge of ancient

writing materials, of paleography, of scribes and

scribal habits, of scribal errors and

transcriptional probabilities, of scriptoria and

their procedures, and of the availability and

mobility of literary texts in the early Christian

world. In a broader context, it also requires

knowledge of the nature, development, and spread

of early Christianity, including details of the

relevant geographical areas, the cultural and

ecclesiastical milieu of Christianity in those

various areas, and the theological and personal

influences that shaped Christian faith. For the

earliest times and even for some later periods,

our

96

3.2.1.2 Transmission

- understanding of the NT text is inhibited by a

lack of detailed knowledge just as often,

perhaps, the neglect of data provided by Church

history has prevented advances in the

discipline." - 2. NT Textual Materials "As early as 1707, John

Mill claimed that the (relatively few) NT mss

examined by him contained about 30,000 variant

readings 200 years later B. B. Warfield

indicated that some 180,000 or 200,000 various

readings had been counted in the then existing

NT mss, and in more recent times M. M. Parvis

reported that examination of only 150 Greek mss

of Luke revealed about 30,000 readings there

alone, and he suggested that the actual quantity

of variant readings among all NT

97

3.2.1.2 Transmission

- manuscripts was likely to be much higher than

the 150,000 to 250,000 that had been estimated in

modern times. Perhaps 300,000 differing readings

is a fair figure for the 20th century." - 3. "It is not difficult to imagine how the NT

writings were employed in the early decades of

Christianity and how they were circulated in that

initial period and in the succeeding decades. For

instance, an apostolic letter or a portion of a

gospel would be read in a worship service

visiting Christians now and again would make or

secure copies to take to their own congregations,

or the church possessing it might send a copy to

another congregation at its own initiative or

even at the request of the writer (cf. Col 416)

and quite rapidly numerous early Christian

98

3.2.1.2 Transmission

- writings-predominantly those that eventually

formed the NT-were to be found in church after

church throughout the Roman world. Naturally, the

quality of each copy depended very much on the

circumstances of its production some copies must

have been made in a rather casual manner under

far less than ideal scribal conditions, while

others, presumably, were made with a measure of

ecclesiastical sanction and official solicitude,

especially as time passed. Great Church centers,

such as Antioch, Alexandria, Ephesus, Rome, Lyon,

and Carthage, must have issued copies of the

Scriptures, or parts thereof, for their

constituent churches, and when the Christian

Church gained the official favor of the Roman

Empire under

99

3.2.1.2 Transmission

- Constantine, the emperor himself commissioned 50

copies of the Scripture on fine parchment. . .

by professional scribes for new churches in

Constantinople (Eusebius, Vita C. 4.36). This

occurred about AD 331, some 280 years after Paul

penned the first of his letters and about 260

years after the first gospel, Mark, was written.

Codices Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, the two oldest

parchment manuscripts of the NT (except for

fragments), are elegant copies of the kind that

Constantine must have had in mind, and they come

from precisely this period-the mid-4th century."

Epp

100

3.2.1.3 Manuscripts

- 1. According to Types of Material

- "Papyrus mss, in codex form, were used by

Christians from the earliest times into the 8th

century. They constitute only 3 of NT

continuous-text mss and less than 2 of all NT

mss, though, of course, far less than that in the

amount of extant Greek NT text, since most of the

papyri are highly fragmentary. Qualitatively,

however, they enjoy an importance inversely

proportionate to the small amount of text they

presently preserve." Epp

101

3.2.1.3 Manuscripts

- 1. According to Types of Material

- "Parchment codices were standard for copies of

the NT text until the very late Middle Ages when

paper finally replaced parchment (14th-15th

centuries) and when printing replaced hand

copying (15th century). Roughly 75 of all Greek

NT mss are on parchment (ca. 4,000, including

some 2,400 continuous-text mss and some 1,600

lectionaries). Paper mss, therefore, are more

common than might be supposed, numbering roughly

1,200 (somewhat evenly divided between the

minuscules and lectionaries) and ranging in date

from the 12th to the 19th centuries, with most

originating in the latter part of this period."

Epp

102

3.2.1.3 Manuscripts

- 1. According to Types of Material

- ". . . around the turn of the 2d/3d century (AD

200), NT mss began to be copied on parchment or

vellum. . . . The stability of parchment also

permitted its reuse, after scraping and washing

the existing writing off the surface such a ms

is called a palimpsest (i.e., scraped again).

Some 50 NT mss prior to the 11th century are

palimpsests, among which the most famous is Codex

Ephraemi Syri Rescriptus (C), whose NT text dates

to the 5th century. " Epp

103

3.2.1.3 Manuscripts

- 2. Calligraphy

- "As for calligraphy, until the 9th century Greek

ms of the NT (both papyrus and parchment) were

written exclusively in uncial script (using

large-sized, unconnected capital letters), and

uncials continued to be employed in the following

century. Minuscule script (using lowercase,

cursive or running - connected - letters) was

used from the 9th century on. The earliest dated

NT minuscule (no. 461) was copied in 835.

Minuscule script, as its name implies, was

smaller, requiring less space, and its connected

style permitted more rapid writing. Minuscules,

therefore, were easier and quicker to produce and

less expensive than uncials, and the legacy of NT

textual materials is likely to

104

3.2.1.3 Manuscripts

- 2. Calligraphy

- be larger than might have been the case had the

uncial hand persisted. About 12 of NT mss are in

uncial script (some 650) and 88 in minuscule

(some 4,650). NT uncial mss are found on papyrus

and parchment, minuscules on parchment and

paper." Epp

105

3.2.1.4 Function Form

- 1. Continuous-Text MS

- ". . . a ms recording the text of at least one NT

book (even if no longer fully preserved) in a

continuous fashion without additional context

(though occasionally an interlinear or separate

commentary to the text may be part of the ms).

These mss may be written on papyrus, parchment,

or paper and may be either in uncial or minuscule

hand. Continuous-text NT mss number about 3,125,

including about 94 different papyri in uncial

script, about 270 different uncial mss on

parchment, and around 2,750 minuscules on

parchment or paper (of which more than 2,100 are

on parchment)." Epp

106

3.2.1.4 Function Form

- 2. Lectionary

- "Lectionaries are mss containing portions of

biblical text for reading in church services. NT

lessons from the Gospels and Epistles are

arranged not in the order of the NT canon, but in

accordance either with the Church year (called

the synaxarion) . . . . Lections vary in length

from a few verses to a few chapters, with a

customary length of about ten verses." Epp - Carefully copied from an exemplar lectionary.

- Basically Byzantine text type.

107

3.2.1.4 Function Form

- 3. Lectionary

- "NT lectionary mss in Greek number around 2,200,

of which nearly 90 (more than 1,900) are

minuscules and the rest uncials (about 270). Two

uncial lectionaries date as early as the 4th and

5th centuries, about seven more in the 6th and

7th, with large numbers originating in the 9th

and 10th, and with vast numbers of minuscule

lectionaries stemming from the 11th and 12th

centuries and thereafter. Over all, 75 are on

parchment, with the rest on paper (dating from

the 12th century on), and the majority of

lectionaries consist of gospel readings." Epp

108

3.2.1.4 Function Form

- 4. Helps

- "Words and sentences usually were not separated

from one another, occasionally leading the reader

to divide words in alternate ways with differing

meanings virtually no punctuation occurred until

the 6th or 7th centuries similarly, breathing

marks and accents are rare prior to the 7th

century, though after this time they occasionally

were added by a later hand to NT lectionary mss

in Greek number around 2,200, of which nearly 90

(more than 1,900) are minuscules and the rest

uncials (about 270)." Epp

109

3.2.1.4 Function Form

- 4. Helps

- "To assist in locating parallel passages in the

gospels, Eusebius (ca. 263-339) devised a system

of ten canons or tables (known as the Eusebian

Canons) that divided the gospel material into

sections and identified those that were found in

all four gospels (canon I), those in each

combination of three gospels (canons II-IV)

those in each combination of two gospels (canons

V-IX), and finally those sections in only one of

the gospels (canon X). Thus, all the possible

combinations were exhausted. Each section in each

gospel was then numbered consecutively, and these

section numbers, along with their appropriate

canons, were placed-in colored ink-in the margin

of a ms.

110

3.2.1.4 Function Form

- 4. Helps

- The reader, by looking up the section number in

the designated canon, could find the numbers of

any parallel sections in other gospels. . . ."

Epp - N.B. Nestle-Aland27, 84-89

111

3.2.1.5 Papyri

- 1. "Presently 96 NT papyri have been identified,

though two of these are portions of others (P33

P58 P64 P67), leaving a total of 94 different

papyri. They range in date from the 2d century to

the 8th, and all but four are from codices (the

four, P12, P13, P18, P22, are from scrolls,

though all are exceptional in that they are

either written on both sides or are on reused

papyrus). These 94 papyri range in extent of

coverage from tiny fragments (like P52 of John)

to extensive portions (in papyri like P66, P75,

and P72)."

112

3.2.1.5 Papyri

- 2. See

- Metzger, The Text of the New Testament, 36-42.

- Kurt Aland Barbara Aland, The Text of the New

Testament, 83-102. - 3. "In Studying any New Testament text it is

important to know in which papyri (and uncials)

it is found. But a great amount of effort is

required to find this information in the

literature." Therefore see charts 5 6 in Aland

Aland

113

3.2.1.5 Uncials

- 1. "As a classification of NT mss, uncials is

not used to refer to all NT mss written in uncial

characters (about 650), but only to

continuous-text mss so written on parchment

(about 270). Thus, the papyri and the more than

270 lectionary mss written in uncials are

classified under papyri and lectionaries,

respectively, and not here." Epp - 2. "Continuous-text uncials total about 290, but

the number of different uncials is closer to 270,

due to the continuing process of uniting

separated fragments with their original mss.

Uncials date from the 2d/3d century through the

10th century. Only 4 predate the early 4th

century (0189, 0220, 0162, 0171) 14 stem from

the 4th century including the two most famous

uncials, Codices Sinaiticus and Vaticanus but 54

114

3.2.1.5 Uncials

- survive from around AD 400 to 500 and uncials

increase as one moves into the later 6th and

through the 9th centuries, with the last 19

originating in the 10th century. . . ." Epp - 3. ". . . in reality only 35 percent of all

uncials survive in more than two leaves. To be

more precise, only 59 uncials (about 22 percent)

contain more than 30 leaves and only 44 uncials

(about 16 percent) have more than 100 leaves. Of

this latter group, 17 contain 100 to 199 leaves

16 have 200 to 299 9 have 300 to 399 and only 2

have more than 400 (Bezae 05 with 415 and

Claromontanus 06 with 533 leaves)." Epp

115

3.2.1.5 Uncials

- 4. "Codex Sinaiticus (a) is the only uncial

presently containing the entire NT (though

Alexandrinus still contains portions of every NT

book). Sinaiticus also has virtually all of the

OT, as well as the Epistle of Barnabas and the

Shepherd of Hermas. It dates from the 4th century

and its large pages contain four columns each-the

only NT ms written in this fashion.

116

3.2.1.5 Uncials

- 5. "Codex Alexandrinus (A) is of somewhat later

date-in the 5th century-and lacks only portions

of Matthew (up to 256), John (650-852), and 2

Corinthians (413-126) from its NT, and it

contains the OT, as well as 1-2 Clement. It is

written in two columns and its text appears to

have been copied from different exemplars, for

its gospel text is akin to the Byzantine type,

while the remainder of the NT has a text like

that in Sinaiticus and Vaticanus."

117

3.2.1.5 Uncials

- 6. "Codex Vaticanus (B), 4th century, is written

in three columns and contains all of the NT

except an extensive portion from Heb 914 through

Revelation it also has the OT, though it begins

with Gen 4628 and lacks Ps 105271376.

Vaticanus would be regarded by all as the most

valuable uncial ms of the NT, and by many as the

most important of all NT mss, due to the

combination of its early date, its broad coverage

of the NT, and the excellent quality of its text,

which-for the overlapping portions-is strikingly

similar to that in P75."

118

3.2.1.5 Uncials

- 7. "Codex Bezae Cantabrigiemis (D) contains, on

Greek and Latin facing pages, the four gospels

(in the order Matthew, John, Luke, Mark), Acts

nearly complete, and a small portion of 3 John.

Its date is 5th century, or possibly late 4th. It

is written in one column, but in sense lines

rather than in the usual fashion of simply

filling the lines. Bezae, with many striking

additions to the text (and some omissions), is

the major Greek representative of the so-called

Western type of text, which some have considered

the earliest form of the NT text, but which

others have viewed as a later, derivative

development."

119

3.2.1.5 Uncials

- 8. "Codex Washingtonianus (W), also known as the

Freer Gospels, has the four gospels virtually

complete (though in the order of Matthew, John,

Luke, and Mark) and dates from the early 5th

century. Its text is of mixed character, with

various sections of varying length representing

rather different textual types Byzantine in

Matthew and most of Luke Alexandrian in the rest

of Luke and most of John and so-called Western

in Mark 11-530, but like the text of P45 in

531-1620. It may be best known for the material

it inserts into the

120

3.2.1.5 Uncials

- already longer ending to Mark (169-20) that it

shares with other witnesses it adds at 1614 a

paragraph that includes an excuse by the

disciples in response to the risen Christs

chiding of them for unbelief." - 8. See also

- Metzger, 42-61.

- Aland Aland, 103-128.

121

3.2.1.5 Minuscules

- 1. "Some 80 percent of the minuscules are solid

representatives of the Majority text and to that

extent at least they will contribute little to

the establishment of the original text, for the

Byzantine or Koine text (to use two other terms

for the Majority text) is a text type that

developed from the early 4th century on and

became the well-established and official

ecclesiastical text of the Byzantine Church."

Epp

122

3.2.1.5 Minuscules

- 2. ". . . approximately 10 percent of them offer

a valuable early text which can compete with even

the best of the uncials." Aland Aland, 128 - 3. See

- Metzger, 61-66

- Aland Aland, 128-158.

123

3.2.1.5 Lectionaries

- 1. "Though the lectionary mss of the NT number

2,200 or more, they are not often cited in the

critical apparatus of Greek NT texts because they

overwhelmingly preserve a Byzantine text and are

not critical in establishing the original NT

text. Greek lectionaries do not include the

Apocalypse, for there were no readings from this

book in the Church year the same applies to some

passages of Acts and the Epistles." Epp - 2. See Aland Aland, 163-170.

124

3.2.1.5 Patristics

- 1. "Passages of the NT quoted by writers in the

early Church constitute an important body of data

for textual criticism, for they provide narrowly

![[PDF⚡READ❤ONLINE] KJV Large Print Personal Size Reference Bible, Charcoal Leathertouch, Red PowerPoint PPT Presentation](https://s3.amazonaws.com/images.powershow.com/10041487.th0.jpg?_=20240529054)

![[PDF] DOWNLOAD NASB, Holy Bible, XL Edition, Leathersoft, Brown, 1995 Text, PowerPoint PPT Presentation](https://s3.amazonaws.com/images.powershow.com/10050095.th0.jpg?_=20240607092)

![[READ] Bible Word Search Read Through The Bible Old Testament Volume 88: Proverbs #1 Extra Larg PowerPoint PPT Presentation](https://s3.amazonaws.com/images.powershow.com/10054381.th0.jpg?_=20240613075)

![❤[READ]❤ NKJV, End-of-Verse Reference Bible, Personal Size Large Print, Leathersoft, PowerPoint PPT Presentation](https://s3.amazonaws.com/images.powershow.com/10072911.th0.jpg?_=20240704111)