Acquiring a Company - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 17

Title:

Acquiring a Company

Description:

... is worth anywhere from 0 to $100 per share (depends on result of oil exploration) ... 1. The number of GM cars produced in 1990. 2. IBM's assets in 1989 ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:30

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Acquiring a Company

1

Acquiring a Company

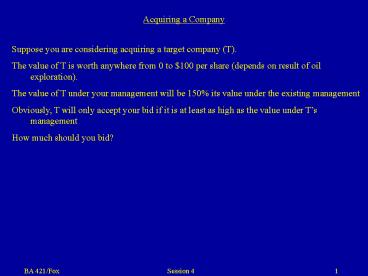

Suppose you are considering acquiring a target

company (T). The value of T is worth anywhere

from 0 to 100 per share (depends on result of

oil exploration). The value of T under your

management will be 150 its value under the

existing management Obviously, T will only accept

your bid if it is at least as high as the value

under Ts management How much should you bid?

2

Acquiring a Company

Value to Target

Target says no

Yes!

100

b

0

Bid from Acquirer

When Target says yes, they are worth b/2 on

average

Therefore they are worth 3/2 (b/2) 3/4 b

on average

But 3/4 b lt b! So on average, the acquirer

loses money!

3

Perspective Biases

Many negotiation errors arise from our inability

to see things from the other sides

perspective. 1) We have a hard time taking

into account information available to the other

side. Acquiring a company Competitive

bidding

4

Perspective Biases

2) We are biased to think that we are in the

right. Confirmation bias/biased

assimilation One-sided evidence B P

D J jurors for Pltf 10.6 12.1 8.5

11.5 egocentric assessments of fairness

5

Perspective Biases

3) We are biased to be suspicious of what the

other side is offering. Fixed pie

bias/lose-lose agreements Reactive

devaluation

6

Reactive Devaluation

The tendency to devalue offers and concessions

merely because they were made by the other side

E.g. Apartheid divestment at Stanford partial

divestment (PD) reward companies that divest

(RD)

T1 PD gt RD T2 RD gt PD

7

90 Confidence Interval

3,213,752 autos 77.7 billion 5.8 billion 67,900

sq. miles 4.16 million 195.7 billion 68.5

inches 1,749,129 vol. 728.9

billion 290,400

1. The number of GM cars produced in 1990 2.

IBMs assets in 1989 3. Total number of 5 bills

in circulation in 1990 4. Total area in square

miles of Lake Michigan 5. Total population of

Barcelona, Spain in 1990 6. The amount of taxes

collected by the IRS in 1970 7. The average

annual snowfall in Anchorage, AK 8. The number of

bound volumes in all 26 branches of the San

Francisco Public Library 9. The dollar value of

outstanding consumer credit at the end of

1988 10. The median price of existing

single-family homes in Honolulu, HI in 1990

8

Positive Illusions

Many negotiation errors arise from our tendency

to maintain an overly optimistic view of our own

attributes, motivation, and ability to secure

favorable outcomes. 1) Overconfidence 2)

Self-enhancing biases

9

Anchoring Insufficient Adjustment

Oftentimes our assessment of what constitutes a

fair or reasonable offer is skewed by salient

numbers that have been introduced in the course

of negotiating. demonstration Real

estate brokers

10

Framing Effects

Our willingness to accept deals and our

aggressiveness bargaining is often affected by

the way in which offers are packaged and

described.

11

Descriptive Theory of Value Prospect Theory

1) Reference dependence people are sensitive to

losses and gains relative to their reference

state (e.g., the status quo). The reference

state can be manipulated through framing. 2)

Diminishing sensitivity people are less and less

sensitive to each additional dollar gained or

lost (i.e., the value function is concave for

gains and convex for losses). 3) Loss aversion

losses loom larger than gains (i.e., the

value function is steeper for losses

than for gains).

value

gains

losses

12

Status Quo Bias (Hershey et al, 1990) Auto

Insurance Policies

NEW JERSEY no-fault () PENNSYLVANIA right to

sue ()

23 buy right to sue 53 retain right

lose right vs. gain

gain right vs. (-gain )

13

Descriptive Perspective Prospect Theory

Note that the value function predicts risk

aversion for gains

risk seeking for losses

value

v(100) v(50)

v(50) gt 1/2 v(100)

-100 -50

gains

losses

50 100

v(-50) v(-100)

1/2 v(-100) gt v(-50)

14

Cognitive and Motivational Biases in Negotiation

Summary

1) Perspective Biases Problem People have

great difficulty compensating for their unique

point of view. They tend to overestimate the

appeal of their own point of view, minimize

concessions made by the other side, and fail to

appreciate the impact of other peoples

information on outcomes, falling prey to the

Winners Curse. Solution In your

preparation, try to play devil's advocate by

carefully considering the strengths of the other

side's case, and especially the weaknesses of

your own. Do your best to investigate the

information available to others that may

influence their behavior. During the

negotiation, critically evaluate concessions made

by the other side, and be wary of your own bias

to underappreciate them.

15

Cognitive and Motivational Biases in Negotiation

Summary

2) Positive Illusions Problem Most people

are overconfident in their accuracy estimating or

forecasting uncertain values, and in their own

ability to get projects accomplished and deals

secured most people have an unrealistically

positive view of their own abilities and

motivations. Solution In your

preparation, try to take the outside view by

considering base rates. Recognize your own

limitations and the extent of your own biases.

16

Cognitive and Motivational Biases in Negotiation

Summary

3) Anchoring insufficient adjustment

Problem We often inadvertently allow a salient,

focal value to skew our perception of what is

fair or feasible in negotiation more than we

should. Solution Prepare for negotiations

by deciding in advance your reservation values,

aspiration values and your best guess of your

opponents reservation values. Consciously

question whether the opponents values offered in

the course of bargaining should cause you to

reevaluate.

17

Cognitive and Motivational Biases in Negotiation

Summary

4) Framing Problem Risk attitudes,

desirability of outcomes, and willingness to make

concessions can be influenced by the way in which

outcomes are framed--as losses or gains, and in

different mental accounts. Solution Try

to view outcomes in terms of a consistent,

positive frame, for example, by translating all

outcomes into dollars or utility points. Try

to encourage your counterpart to frame outcomes

in a way that is advantageous to you.