Process-oriented surface-wave tomography - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 70

Title:

Process-oriented surface-wave tomography

Description:

xapGImg:image /9j/4AAQSkZJRgABAgEASABIAAD/7QAsUGhvdG9zaG9wIDMuMAA4QklNA ... xA;fvOvKnPI4 GvSw1fjcX7278/0dK92ycZNxXYq7FXYq7FUBrv6C/RU/6e q/omg tfXvT r8a inqe ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:71

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Process-oriented surface-wave tomography

1

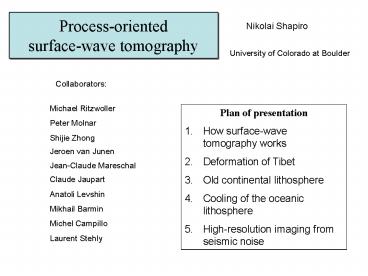

Process-orientedsurface-wave tomography

Nikolai Shapiro

University of Colorado at Boulder

Collaborators

Michael Ritzwoller Peter Molnar Shijie

Zhong Jeroen van Junen

- Plan of presentation

- How surface-wave tomography works

- Deformation of Tibet

- Old continental lithosphere

- Cooling of the oceanic lithosphere

- High-resolution imaging from seismic noise

Jean-Claude Mareschal Claude Jaupart Anatoli

Levshin Mikhail Barmin Michel Campillo Laurent

Stehly

2

common belief

main point of this talk

Surface-wave tomography can be used to study

processes in the Earths crust and upper mantle

- Improvement of resolution (short-period

measurements) - Conversion into physical parameters

- Combining with other types of geophysical

information - Physically motivated parameterization of seismic

models

3

Seismic data

How surface-wave tomography works

Body waves sample deep parts of the Earth Surface

waves sample the crust and upper mantle

4

Seismic surface-waves

How surface-wave tomography works

- Two types Rayleigh and Love

- Dispersion travel times depend on period of wave

- Two types of travel time measurements phase and

group

5

1. Dispersion measurements

How surface-wave tomography works

- More than 200,000 paths across the Globe

- Rayleigh and Love wave phase velocities (40-150

s) - (Harvard, Utrecht)

- Rayleigh and Love wave group velocities (16-200

s) - (CU-Boulder)

6

2. Dispersion maps

How surface-wave tomography works

100 s Rayleigh wave group velocity

7

3. Local dispersion curves

How surface-wave tomography works

All dispersion maps Rayleigh and Love wave group

and phase velocities at all periods

8

4. Inversion of dispersion curves

How surface-wave tomography works

All dispersion maps Rayleigh and Love wave group

and phase velocities at all periods

Monte-Carlo sampling of model space to find an

ensemble of acceptable models

9

3D seismic model

How surface-wave tomography works

combination of 1D seismic profiles from all

locations

horizontal slices at 150 km depth

vertical slices

10

regional studies

JGR, 2002

JGR, 2003

Geology, 2005

Nature, 2002

11

Andaman-Sumatra region

12

Quantitative interpretation of seismic

tomographic models

- S-wave speed - temperature (composition)

- anisotropy - strain

- Problems

- inversions are over-parameterized and non-unique

- (combining with other geophysical data

- physically motivated parameterization)

- limited resolution

- (measurements at short periods and along

short paths)

13

Seismic anisotropy and deformation of Tibetan

crust

Discrepancy between inversely dispersed Rayleigh

waves and normally dispersed Love waves at

periods lt 30 s

14

Discrepancy between inversely dispersed Rayleigh

waves and normally dispersed Love waves at

periods lt 30 s

15

Explanation of short-period Rayleigh-Love

discrepancy radial anisotropy within mid-lower

crust

34N 84E

- Anisotropy maximizes In the Western Tibet

- lttSV-tSHgt 0.50.18 s

16

Radial anisotropy vertical slow axes of

symmetry- Likely mechanism of the radial

anisotropy near-horizontal alignment of mica

crystals

- Tectonic process that can cause the radial

anisotropy - Shearing during the underthrusting

- Crustal thinning and flow

17

Relation between crustal thinning and radial

anisotropy

- Mid-crustal deformation (30) is stronger than

the surface deformation (10) - Tibetan middle crust is mechanically weak

30 km layer with 30 of mica

18

Thermal models of the old continental lithosphere

from Jaupart and Mareschal (1999)

from Poupinet et al. (2003)

- Constrained by thermal data heat flow, xenoliths

- Derived from simple thermal equations

- Lithosphere is defined as an outer conductive

layer - Estimates of thermal lithospheric thickness are

highly variable

19

Seismic models of the old continental lithosphere

- Based on ad-hoc choice of reference 1D models and

parameterization - Complex vertical profiles that do not agree with

simple thermal models - Seismic lithospheric thickness is not uniquely

defined

Additional physical constraints are required to

eliminate non-physical vertical oscillations in

seismic profiles and to improve estimates of

seismic velocities at each particular depth

20

Using heat-flow data to constrain seismic

speedsat the top of the mantle

- Computation of end-member crustal geotherms

- Conversion into seismic velocity bounds

- Extrapolation of temperature and seismic speed

bounds over a large areas

21

Using heat-flow data to constrain seismic

speedsat the top of the mantle

seismically acceptable models

22

Using heat-flow data to constrain seismic

speedsat the top of the mantle

seismically acceptable models

23

Using heat-flow data to constrain seismic

speedsat the top of the mantle

seismically acceptable models

24

Thermal parameterization of the old continental

uppermost mantle

25

Lithospheric thickness and mantle heat flow

- Seismic inversions can be reformulated in terms

of an underlying thermal model. - Lithospheric thickness beneath cratonic cores

exceeds 250km. - Mantle component of the heat flow beneath cratons

is low ( lt 15 mW/m2). - Power-law relation between lithospheric thickness

and mantle heat flow is consistent with the model

of Jaupart et al. (1998) who postulated that the

steady heat flux at the base of the lithosphere

is supplied by small-scale convection.

26

Cooling of the Pacific lithosphere

Half-space cooling (HSC) model

T(z, A) Tm erfc(0.5z(kA)-0.5) A - lithospheric

age

A0.5

A-0.5

predictions of the standard model agree with

observations only at young ages

27

Possible explanations of the arrested cooling of

the Pacific lithosphere

- mantle plumes

- elevated mantle temperature in the past

- small-scale convection (SSC)

Numerical simulations of SSC by S. Zong, J. van

Hunen et J. Huang

details of the predicted structure depend on

mantle rheology

28

Dispersion maps

29

Dispersion maps

30

Inversion of dispersion curves

- non-physical oscillations in resulting thermal

models - physical interpretation problematic

Traditional approach ad-hoc parameterization of

seismic models

32N 160W

- thermally consistent modes

- inversion directly for physical parameters

32N 160W

31

3D seismic model

32

Apparent thermal age of the Pacific lithosphere

33

Small-scale convection can explain the observed

arrested cooling

34

Constraints on the upper mantle rheology

Ea activation energy

Laboratory measurements (Karato and Wu,

1993) Linear rheology (n1) Ea 240-300

KJ/mol Non-linear rheology (n3) Ea 430-540

KJ/mol

Best agreement between observations and

laboratory measurements is obtained with

non-linear rheology (dislocation creep)

35

Conclusions

- Seismic inversions can be reformulated in terms

of an underlying thermal model. - This allows us to infer simple thermal parameters

that can be directly compared with predictions of

geodynamical models. - Comparison with numerical simulations show that

- - the structure of the old Pacific

lithosphere is controlled by small-scale

convection - - deformation of the uppermost mantle is

controlled by the dislocation creep (non-linear

rheology)

36

Resolution of seismic tomographic models of the

crust and the uppermost mantle

- Seismic tomography is traditionally based on

direct waves from earthquakes - Distribution of earthquakes and seismic stations

is inhomogeneous - In many regions, surface-wave tomography is based

on long pathes

- Problems with long paths

- Extended sensitivity kernels

- Difficult to make short-period measurements

- Consequence limited resolution

Solution measurements independent of

earthquake locations

37

(No Transcript)

38

(No Transcript)

39

(No Transcript)

40

(No Transcript)

41

By computing cross-correlation of seismic noise

records at two stationswe can extract

surface-waves propagating between these stations

42

Cross-correlation of seismic noise in California

43

(No Transcript)

44

Sierra Nevada

Sacramento basin

Franciscan formation

Peninsular Ranges

Salinean block

San Joaquin basin

45

Central Valley

Vantura basin

Imperial Valley

LA basin

46

Comparison between noise-based and

earthquake-based tomographies

47

Extraction of surface waves from seismic noise

Measurements without earthquakesImproved

resolutionPossible applications -

imaging of the crust and the uppermost mantle

- structure of sedimentary basins for seismic

hazard - seismic calibration for nuclear

monitoring Remaining questions - optimal

duration of noise sequences - spectral

range - optimal inter-station distances

- Other than Rayleigh waves (Love, body waves)

48

the end

49

(No Transcript)

50

Tibet cartes de dispersion longues-périodes

At short periods, group velocities are slow

because of the thick, slow crust At long periods,

group velocities are neutral to fast because the

crust is compensated by fast material in the

upper mantle

51

Tibetan Mantle Structure depth slices

52

(No Transcript)

53

(No Transcript)

54

(No Transcript)

55

(No Transcript)

56

Anisotropie azimutale de vitesse de groupe

Amplitudes larger in the young than the old

Pacific. Large amplitudes trend NW from the

EPR. Fast axes align perpendicular to the EPR

at all periods. 100 s 150 s maps similar

across the Pacific. 25 s 50 s maps mostly

similar. Contrast 50 s 150 s maps in the

old Pacific.

57

Comparaison de lanisotropie azimutale avec la

direction de mouvement des plaques

Present-Day Plate Motion

HS3-NUVEL-1A (Gripp Gordon, 2002)

58

Comparaison de lanisotropie azimutale avec la

direction de mouvement des plaques

Present-Day Plate Motion

HS3-NUVEL-1A (Gripp Gordon, 2002)

59

Comparaison de lanisotropie azimutale avec la

direction de mouvement des plaques

50 sec Avg difference 34 deg lt30 Ma -- 20

deg gt70 Ma -- trend from 25 - 60 deg

150 sec Avg difference 17 deg lt30 Ma -- 10

deg gt70 Ma -- 20 deg

60

Différence entre lanisotropie azimutale et le

mouvement des plaques

Near the EPR fast axes align nearly perpendicular

to PPM at all periods. At 70 My, agreement

begins to break down at short and

intermediate periods. Beyond 100 My,

disagreement is severe at periods below 80

s. Thus, in the shallow lithosphere (lt75 km) in

the old Pacific fast axes are not aligned with

present plate motions, but they are in the

underlying asthenosphere (gt125 km).

61

Comparaison de lanisotropie azimutale avec la

direction de paleo-extension aux dorsales

océaniques

Paleo-Spreading Directions

Determined from the gradient of lithospheric age.

Mueller et al., 1997

62

Comparaison de lanisotropie azimutale avec la

direction de paleo-extension aux dorsales

océaniques

Paleo-Spreading Directions

63

Comparaison de lanisotropie azimutale avec la

direction de paleo-extension aux dorsales

océaniques

50 sec Avg difference 17 deg lt30 Ma -- 15

deg gt70 Ma -- no trend

150 sec Avg difference 25 deg lt30 Ma --

20 deg gt70 Ma -- trend from 30 - 45 deg

64

Stratification de lanisotropie sous le Pacifique

- At large scales the story that emerges is a

pretty simple one of - anisotropy stratification

- In the deep lithosphere

- asthenosphere, anisotropic

- fast axes conform with current

- plate motions.

- In the shallow lithosphere

- (lt75 km), fast axes appear to

- be fossilized, aligning closer

- to the paleo-spreading directions.

65

Nouvelle méthode tomographie sismique de haute

résolution à partir de bruit sismique

66

(No Transcript)

67

Mechanisms to Produce Stratification of

Anisotropy Beneath the Pacific

68

(No Transcript)

69

Azimuthal Anisotropy Fast Axis Directions vs

Paleo-Spreading Directions

Paleo-Spreading Directions

70

Amplitude of Azimuthal Anisotropy as a Function

of Age