PowerPoint Poster Template - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 1

Title:

PowerPoint Poster Template

Description:

Development and validation of a scale for hypomanic personality. ... in response to the happy and pride film stimuli ... ( 2) Film clips are a passive means of ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:383

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: PowerPoint Poster Template

1

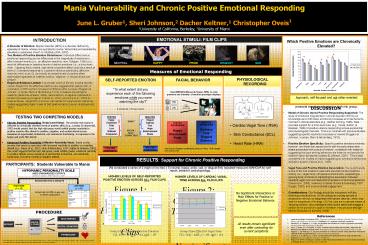

Mania Vulnerability and Chronic Positive

Emotional Responding June L. Gruber1, Sheri

Johnson,2 Dacher Keltner,1 Christopher

Oveis1 1University of California, Berkeley,

2University of Miami

- INTRODUCTION

- A Disorder of Emotion Bipolar Disorder (BPD) is

a disorder defined by episodes of mania whose

core symptoms involve abnormally and

persistently elevated or expansive mood or

irritability (APA, 2002). - Two Models of Positive Emotion Disturbance

Individual differences in emotional responding

can be differences in the magnitude of reactions

to affect-relevant events (i.e., an

affective-reactivity view Tellegen, 1985) or a

result of differences in baseline levels of

distinct emotions (i.e., a tonic-level view).

Applying this to mania, high levels of positive

affect could be a result of either (1) increased

response to a positive stimulus specifically

(affective-reactivity view) or as (2) chronically

increased levels of positive affect observable

regardless of whether positive, negative, or

neutral stimuli are present. - Empirical Evidence Limited It is unclear which

of the two models best fits mania. Support for

the affective-reactive view suggests that people

with, or vulnerable, to BPD exhibit increased

confidence after success (Ruggero Johnson, in

press Stern Berrenberg, 1979), increased

physiological reactivity (Sutton Johnson,

2002), neural activity in regions implicated in

emotion processing (Yurgelun-Todd et al., 2002

Lawrence et al., 2004) to positive stimuli.

Support for the tonic-view stems from

experience-sampling studies suggesting higher

levels of trait positive mood (Lovejoy

Steuerwald, 1995).

EMOTIONAL STIMULI FILM CLIPS

Which Positive Emotions are Chronically Elevated?

HAPPY

DISGUST

PRIDE

SAD

NEUTRAL

Measures of Emotional Responding

PHYSIOLOGICAL RECORDING

SELF-REPORTED EMOTION

FACIAL BEHAVIOR

To what extent did you experience each of the

following emotions while you were watching the

clip? 1 (not at all) ? 5 (very much)

Used EMFACS (Ekman Friesen,1978) to code

presence and intensity of emotion prototype

displays.

Approach, self-focused and not other-oriented

prosocial emotions elevated in high risk group.

- Model of Chronic (tonic) Positive Responding

Supported The study of emotional irregularities

in clinical disorder informs our knowledge as to

both basic emotional processes and mechanisms

involved in clinical disorders (e.g., Keltner

Kring, 1998). Data provides support for a

tonic-level view (e.g., Gross, Sutton,

Ketelaar, 1998) of positive valence responding

across experiential and physiological channels.

This is in contrast with previous studies

suggesting specific reactivity to success or

reward (Ruggero Johnson, in press Stern

Berrenberg, 1979). - Positive Emotion Specificity Specific positive

emotions involved, however, are those that appear

tied to self-focused pleasurable states

associated with pursuit of reward , consistent

with research suggesting that goal striving

behaviors are linked to and predict the onset of

manic symptoms (Lozano Johnson, 2001). This is

also consistent with models of mania suggesting

an overactive behavioral activation system (Depue

et al., 1985). - Vagal Tone and Positive Emotion Association The

current study is one of the first studies to

associate elevated parasympathetic activity

(i.e., vagal tone) with positive emotionality,

supporting a growing body of literature

implicating the association between elevated

vagal tone and dispositional positive emotional

experience (Oveis et al., 2005), resiliency to

stress (Fabes Eisenberg, 1997 Porges, 1995),

and environmental engagement. - Considerations Our findings should be

interpreted with the following considerations

(1) We utilized an analog sample of students at

risk but not diagnosed with bipolar disorder,

which may limit the magnitude of findings. (2)

Film clips are a passive means of inducing

emotion, thus paradigms that involve tasks that

engage a person in the pursuit of a goal or

incentive, may produce stronger effects

(Dickerson Kemeny, 2004).

DISCUSSION

- TESTING TWO COMPETING MODELS

- Chronic Positive Responding (Tonic-Level View)

The premise that mania is reflected by

chronically elevated levels of positive affect

(e.g., Lovejoy Steuerwald, 1995) would predict

that the high risk group would exhibit greater

reactivity to positive emotion film stimuli to

positive, negative, and neutral stimuli across

measures of experiential, behavioral, and

autonomic functioning. in response to the happy

and pride film stimuli - Enhanced Positive Reactivity (Affective-Reactivity

View) Based on the premise that mania is

associated with increased reactivity to positive

or rewarding stimuli (e.g., Meyer et al., 2001

Stern Berrenberg, 1979 Sutton Johnson,

2002), this would suggest that the high risk

group would exhibit greater emotional reactivity

to positive stimuli, across measures of

experiential, behavioral, and autonomic

functioning, but not to neutral or negative

stimuli.

BASIC

NEGATIVE EXPRESSIONS Sadness Fear Disgust Distres

s

POSITIVE EXPRESSIONS Happy Amusement Pride

- Cardiac Vagal Tone ( RSA)

- Skin Conductance (SCL)

- Heart Rate (HRA)

SOCIAL/ SELF- CONSICOUS

NEG EMO COMPOSITE

POS EMO COMPOSITE

Intra-Class Correlation Coefficients (Shrout

Fleiss, 1979) ranged from 0.82 to 0.95.

RESULTS Support for Chronic Positive Responding

Results

PARTICIPANTS Students Vulnerable to Mania

We conducted a series of 2 (high or low risk) x 5

(neutral, happy, pride, sad, or disgust film)

repeated-measures MANOVA for self-report,

behavior, and physiology.

HYPOMANIC PERSONALITY SCALE USED STANDARDIZED

CUTOFFS (Eckblad Chapman, 1986 Kwapil et al.,

2000)

HIGHER LEVELS OF SELF-REPORTED POSITIVE EMOTION

ACROSS ALL FILM CLIPS

HIGHER LEVELS OF CARDIAC VAGAL TONE ACROSS ALL

FILM CLIPS

RECRUITED INTO 2 GROUPS

No Significant Interactions or Main Effects for

Positive or Negative Emotional Behavior.

Figure 1 Reported Positive Emotion Across All

Film Clips

HIGH RISK (n 35)

LOW RISK (n 86)

Figure 2 Cardiac Vagal Tone Across All Film Clips

Groups did not differ in age, sex, or ethnic

composition

PROCEDURE

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2002).

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders, Fourth Edition, Quick Reference Text

Revision. Washington, DC American Psychiatric

Association. - Eckblad, M., Chapman, L. J. (1986). Development

and validation of a scale for hypomanic

personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95,

214-222. - Gross, J., Sutton, S.K. Keteelar, T. (1998).

Relations between affect and personality Support

for the affect-level and affective reactivity

views. Personality and Social Psychology

Bulletin, 24(3), 279-288. - Ruggero, C., and Johnson, S. L. (In press).

Reactivity to a laboratory stressor among

individuals with bipolar I disorder In full or

partial remission. Journal of Abnormal

Psychology. - Lozano, B. L. Johnson, S. L. (2001). Can

personality traits predict increases in manic and

depressive symptoms? Journal of Affective

Disorders, 63, 103-111 - Porges, S.W. (1995). Orienting in a defensive

world Mammalian modifications of our

evolutionary heritage A Polyvagal Theory.

Psychophysiology, 32, 301-318.

SELF-REPORT

All results remain significant even after

controlling for current symptoms.

WATCH 5 FILMS

RECRUIT

FACIAL BEHAVIOR

Group Main Effect for Positive Emotion F(1,

117) 8.75, p lt .01, ?p2 .07 No significant

differences for self-reported negative emotion.

Group Main Effect for Vagal Tone F(1, 114)

4.85, p .03, ?p2 .04 No significant

differences in SCL or Heart Rate.

PHYSIOLOGY

We measured current symptoms of mania (ASRM

Altman et al., 1997) and depression (BDI Beck

Steer, 1993) to ensure any claims we made about

emotional responding were independent of current

symptoms.