ECON 301 Week 4: Tues 5th August 1 pm - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 24

Title:

ECON 301 Week 4: Tues 5th August 1 pm

Description:

TC shifts in product demand curves and changes in demand elasticities both of ... Married women balancing child care with P/T work. Older workers phasing into ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:37

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: ECON 301 Week 4: Tues 5th August 1 pm

1

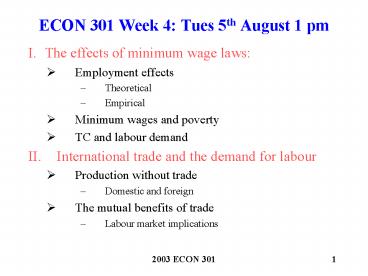

ECON 301 Week 4 Tues 5th August 1 pm

- I. The effects of minimum wage laws

- Employment effects

- Theoretical

- Empirical

- Minimum wages and poverty

- TC and labour demand

- International trade and the demand for labour

- Production without trade

- Domestic and foreign

- The mutual benefits of trade

- Labour market implications

2

I. The effects of minimum wage laws

- Designed to gaurantee workers a resonable wage

for their work effort and to reduce the incidence

of poverty.

3

Employment effects Theoretical analysis

- Standard neoclassical analysis tells us that

higher wages for low-paid workers reduces

employment opportunities for the least-skilled or

least-experienced. - If demand is elastic then ?E is greater than

the ?W and aggregate earnings of low-wage

workers will fall. - Good research must be guided by good theory.

- Issues that must be addressed by research into

the minimum wage include - Nominal vs. real wages

- Min wages are set in nominal terms ie. in s/hr

BUTgeneral price inflation gradually lowers the

real minimum wage changing incentives for

employers SO - Must divide the Wmin by average hourly earnings

- Must allow for regional differences in wages and

prices.

4

Holding other things constant

- We want to measure the employment effect of a

higher minm wage only. But what if labour demand

in that sector is growing?

5

Effects of uncovered sectors

- Non-supervised and non-complying firms.

- As total supply of labour to both sectors is

fixed an ?Wmin in the covered sector reduces

employment there ? supply to the uncovered sector

? ?W there.

6

Intersectoral shifts in product demand

- Product price changes depend on the proportion of

the low-wage labour cost to total cost of

production. Where this proportion is lower cf.

other sectors relative output prices may fall

leading to a scale effect which dominates

increasing the employment of this now higher

waged labour. - So increased minimum wages can increase

employment in some subsectors but at the expense

of others. - Need to look at entire sectors not individual

firms or subsectors.

7

Employment effects Empirical effects

- Results are sensitive to research design or

methodology. - Some results give no (others a ve) effect on

employment of an increase in the minm wage for

teenagers. - Labour demand elasticities are typically of the

order of - 0.1 to 0.3 for teenagers covered by minm wage

legislation. - One explanation is the monopsony model and how

employment increases in the face of mandated wage

increases. - Does the minimum wage fight poverty

- DL is at worst very inelastic then a minm wage

increase should increase total earnings going to

the low-wage workers as a whole. - However most teenagers benefitting from the minm

wage increase come from non-poor families. - So the minm wage is a relatively blunt instrument

with which to reduce poverty.

8

Technological Change and labour demand

- TC ? shifts in product demand curves and changes

in demand elasticities both of which influence

own-wage labour demand elasticities. - The introduction of new products often requires

painful adjustment to the new environment. - TC ? can lead to the substitution of new K for L

but where L and the new K are gross complements a

fall in the product price ? an increase in the

demand for L (usually skilled). - Even factors that are substitutes in production

can be gross complements (if scale effects are

large enough). - TC ? scale effects which change the composition

of E.

9

II. International trade and the demand for labour

- The more open an economy the greater are X IM

to GDP (58 for NZ approx 25 for the US). - The public are often inclined to support laws

which restrict free trade b/c of the view that

low foreign wages will inevitably cause

employment losses at home. - But the effects of trade on the Ld is analogous

to the effects of TC and that two countries will

generally find trade mutually beneficial

regardless of their respective wage rates. - Ch 4A 2 countries (US China) 2 goods (food

and clothing) USs LF 100m Chinas LF 500m

10

Figure 4A.1

Hypothetical Production Possible Curves,

United States

x

-0.9

x

-0.5

11

Figure 4A.2

Hypothetical Production Possibilities Curves,

China

12

Labour market implications

- Trade is determined by the relative internal

(real) costs of production and not by the living

standards (real wages) in two different

countries. - Trade can cause employment to shift across

industries which ? UEt if workers, employers or

mkt wages are slow to adjust. - However theres no reason for this UEt to become

permanent and trade does not condemn jobs in high

wage countries to extinction.

13

ECON 301 Week 4 Wed 6th 12 - 12.50 pm

- I. Quasi-fixed costs and their effects on labour

demand - These are nonwage labour costs ie.

- Hiring and training costs

- Employee benefits eg. holiday and sick pay

entitlements, ACC, superanuation and redundancy

payments - These are borne by the firm on a per-worker basis

and are mostly independent on hours worked. - They explain why some firms prefer to work their

existing workforce longer on penal rates rather

than hiring more staff.

14

I. Training costs

- Explicit monetary costs

- in hiring trainers and

- of materials used in the training process

- Implicit costs

- of using capital and experienced workers

suboptimally - of the employees time

- Recruitment agencies can reduce total time spent

screening and interviewing from 22 hrs to 15 hrs. - Another study indicated that 1/3 of new workers

1st 3 months was spent in some form of training. - The high-wage low-wage strategy.

15

Employee benefits

- Accident compensation, superannuation, holiday

and sick pay entitlements, and other legally

required payments can be as much as 30 of total

remuneration. - These non-wage benefits have been growing over

time. - Many of the non-wage costs are costs per worker

rather than costs per hour worked. - In the US UEt insurance is another quasi-fixed

cost.

16

The employment hours trade-off

- Our simple model of lab demand assumed L had to

increase to produce more Q in the short run but - if instead average hours per employee increased

then - we can think of the MPL as two marginal products

- MPM (where M denotes the no of workers hired) and

the - MPH (where H denotes the average no of hrs each

works) - Both MPM and MPH are positive and subject to

diminishing returns - What is the optimal employment/hours combination?

- To minimise the cost of producing any level of Q

- MEM MEH

- MPM MPH

17

The Predicted Relationship Between MEM/MEH and

Overtime Hours

Figure 5.1

If MEM rises relative to MEH rises more overtime

is worked. What would an increase in penal rates

to double time do for Overtime? Increased

employment?

18

What about the part-time to full-time employment

mix?

- This ratio has increased substantially over the

past 4 decades. WHY? - Supply side reasons

- Married women balancing child care with P/T work

- Older workers phasing into retirement

- Students wanting to finance their education

- Demand side reasons

- Growth in the share of service sector employment

opportunities - Any legislation which madates an increase in

quasi-fixed costs of P/T emploment will reduce

P/T empoyment.

19

Investment in hiring and training increase the

MPL in future periods ie. MP1 gt MP0

Effects of Training on Marginal Products Schedules

- Figure 5.2

20

Multiperiod Demand for Labour

Figure 5.3

The firm should employ labour up to the point

where the PVP PVE ie. MP0 MP1/(1 r) W0

Z W1/(1 r) or W0 Z - MP0 (MP1 - W1)/(1

r)

21

General and specific training

- general training increases an individuals

productivity to many employers - specific training increases an individuals

productivity only to the firm theyre employed

with - eg. compare teaching a person to use a computer

program vs. training someone to use a plant

specific machine. - If the individual undertakes general training

that increases their worth to MP1 then they will

force workers to pay the full costs of their

training by paying wages less than their MP0 by

an amount equal to the direct training costs. - If the individual receives specific training

that increases their worth to MP1 then they can

offer to pay for the training b/c they can pay a

wage W1 above W but below MP1 (allowing them to

recoup investment costs).

22

A Two-Period Wage Stream Associated with Specific

Training

Figure 5.4

The degree of worker mobility will determine how

far below W in the 1st period and how far above

W in the 2nd period they must pay to induce

those workers to stay.

The higher W0 is relative to MP0 during

training, the greater are the training costs

borne by the firm.

23

Figure 5.5

Productivity and Wage Growth, First Two Years on

Job, by Occupation and Initial Hours of

Employer Training

24

Next Week Tue 11th Aug 1 1.50 pm

- Begin labour supply so over the next 2 weeks read

Chs 6 and 7 of ES. - 2nd Tutorial on Thurs 7th of August.