Questionnaire Development - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 61

Title:

Questionnaire Development

Description:

Learn steps to develop survey questions ... Survey = A project used to gather information ... the program participants you survey were different from those you ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:253

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Questionnaire Development

1

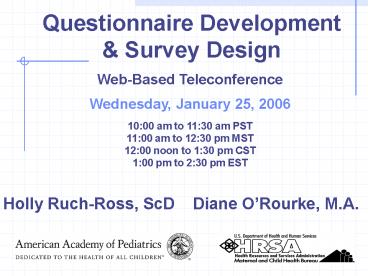

Questionnaire Development Survey Design

Web-Based Teleconference Wednesday, January 25,

2006 1000 am to 1130 am PST 1100 am to 1230

pm MST 1200 noon to 130 pm CST 100 pm to 230

pm EST

Holly Ruch-Ross, ScD Diane ORourke, M.A.

2

Teleconference Objectives

- Determine if a questionnaire is right for you

- Describe types of questionnaires

- Learn steps to develop survey questions

- Discuss issues related to understanding

communicating your results

3

Definitions

- Survey A project used to gather information

- Questionnaire A tool used to collect

information from your target

population

A questionnaire is often a tool used in a survey

project.

Note In these slides, questionnaire is sometimes

abbreviated as Q, and R stands for

respondent, the person answering the questions.

4

Before You Start

- Be very clear about what you need to learn

- What are the questions you have about your

program? - What questions emerge from your programs

objectives? - Know how you are going to use the information you

collect, including how you will analyze it. - Consider the best method to collect the

information you need.

5

Is a questionnaire suitable for what you need to

learn?

A questionnaire is most useful for assessing

- Demographic Characteristics or Facts

- Knowledge

- Attitudes

- Behavior

- When self-report is appropriate/adequate

6

Is a questionnaire suitable for what you need to

learn?

A questionnaire may be less suited to

- Understand underlying feelings and motivations

- Study specific issues in depth and detail

- In general, how and why questions may not be

as well answered as who, what, where,

when, and how many questions

7

Is a questionnaire suitable for what you need to

learn?

A questionnaire may be less useful if

- There are cultural, language or literacy issues

with the target population - You know very little about the target population

or the specific topic of interest - You do not have good access to the target

population - The number of participants is small

- Staff does not have expertise or experience in

design or administration of questionnaires and/or

analyzing results

8

Is there an alternative way to find out what you

need to know?

- See if literature on the topic already exists

- Talk to colleagues and community partners about

information they may have - Check for existing data in your community

- Consider what information you already have

collected (as a part of needs assessment, service

delivery or for other purposes)

9

Once youve decided that a questionnaire is the

best option

THE REAL WORK BEGINS!

10

Questions that need to be answered before you

start creating a questionnaire

- Are there existing tools (sets of questions) that

you can use instead of writing new questions? - When and how will information be collected?

- Who will collect it?

- How will participants be tracked (if follow-up is

planned)? - Who is responsible for data handling?

- How will participant confidentiality be

protected? (HIPPA, etc.) - How/Who will analyze the data?

11

Ways to Administer a Questionnaire to Your Target

Population

- Interviews

- Personal (Face-to-Face)

- Telephone

- Self-administered

- Web

- On-site (school, clinic, etc.)

- Combination of Methods

12

Personal Interviewing

ADVANTAGES

- Generally yields highest cooperation and lowest

refusal rates - Allows for longer, more complex interviews

- High response quality

- Takes advantage of interviewer presence

- Multi-method data collection

- Literacy levels are not a major concern

13

Personal Interviewing

DISADVANTAGES

- Most costly mode of administration unless at

sites - Longer data collection period

- Interviewer concerns (Bias)

14

Telephone Interviewing

ADVANTAGES

- Less expensive than personal interviews

- Shorter data collection period than personal

interviews - Interviewer administration (vs. mail)

- Better control and supervision of interviewers

(vs. personal) - Better response rate than mail

- Literacy levels are not a major concern

15

Telephone Interviewing

DISADVANTAGES

- Biased against households without telephones,

unlisted numbers - Issue of calling cell phones

- Questionnaire constraints

- Difficult for sensitive questions or complex

topics

16

Self-Administered Mail Questionnaires

ADVANTAGES

- Generally lower cost than interviews

- Less staffing (no interviewers)

- Easier access to respondents

- Respondents can look up information or consult

with others - Respondents can fill out questionnaire at leisure

17

Self-Administered Mail Questionnaires

DISADVANTAGES

- Most difficult to obtain cooperation

- More burden on respondent

- Need good address information

- More likely to need an incentive for respondents

- Slower data collection period than telephone

- Literacy levels must be considered

18

Self-Administered Web Questionnaires

ADVANTAGES

- Lower cost (no paper, postage, mailing, data

entry costs) - Time required for implementation reduced

- Complex skip patterns can be programmed

- Sample size can be greater

DISADVANTAGES

- Usually not an accessible method for underserved

populations

19

On-Site Questionnaires

ADVANTAGES

- Easy access to respondents (school, clinic, etc.)

- Group administration possible

- Can be an interview or self-administered

questionnaire

DISADVANTAGES

- May produce biased sample (some students not in

school, some people needing care not at clinic ) - Setting may produce socially desirable results

(e.g., satisfaction with clinic) - If self-administered, must consider literacy

levels

20

When choosing the type of questionnaire, you

must also consider

Language Barriers

- If Self-administered Q

- Translate to another/other language(s)

- If Interview

- Translate into another/other language(s) OR

- Have bilingual interpreters or translators on the

spot - Other Possibilities

- For a self-administered Q, tape record the Q in

the other language (respondent uses headphones to

listen and respond) - -Must be literate enough to fill in the answers

- Have help from the family/another who is

bilingual (CAUTION!)

21

When choosing the type of questionnaire, you

must also consider

Staffing Needs

- Someone with knowledge of Q design (and sampling,

if applicable) - Clerical tasks (mailing Qs, interviewer

assignments, etc.) - Trained interviewers and supervisors, if

applicable - (Special issues if using volunteers/staff as

interviewers) - Data entry/computer programming skills

22

The Art Of QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN

5 Steps to Developing a Questionnaire

- Drafting questions

- Drafting response categories

- Ordering the questions

- Including appropriate instructions

- Pre-testing and revising

23

1. Drafting Questions

What is a Good Question?

- One that yields a truthful, accurate answer

- One that asks for one answer on one dimension

- One that accommodates all possible contingencies

of response - One that uses specific, simple language

- One that minimizes social desirability

- One that is pretested

24

What is Social Desirability?

- Respondents will try to represent themselves to

the interviewer (or on the questionnaire) in a

way that reflects positively on them - As questions become more threatening, respondents

are more likely to overstate or understate

behavior, even when the best question wording is

used

25

Minimizing Social Desirability

- Use a self-administered Q rather than an

interview (dont have to confess to an

interviewer) - Ask a longer question, including reasons for the

socially undesirable behavior (e.g., Many people

find it very hard to find time to exercise) - Use the answer categories to soften the

behavior (e.g., Average number of drinks per day

None, 1, 2, 3, 4-6, 7-9, 10) (rather than None,

1, 2, 3) - Ask for an open-ended response (no categories

given) _____ drinks

26

Drafting Questions

Ask only 1 question at a time

- Beware of AND and OR

- Bad Examples

- How would you rate the support OR assistance you

received through this program? - Do you agree or disagree that this program

helped you to learn more about foods AND eat

better?

27

Drafting Questions

Alternatives to Yes/No

- Its easier to say yes than no

- So.

- Rather than ask Do you like A?

- ask Do you like A or do you like B?

28

Alternatives to Yes/No

- Rather than ask

- Are you satisfied with A?

- Ask

- How satisfied are you with A?

- Would you say you arevery satisfied, somewhat

satisfied, not too satisfied, not at all

satisfied?

29

Alternatives to Yes/No

You can also ask the question this way

- How satisfied or dissatisfied are you with A?

- Would you say you arevery satisfied, somewhat

satisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, very

dissatisfied?

30

Drafting QuestionsOPEN VS. CLOSED

QUESTIONS

- General rule closed questions (response

- categories given) are usually better

- Easier for the respondent

- Less coding later

- Better to have respondent do categorizing

- Categories help define the question

31

Disadvantages of Closed Questions

- Categories may be leading to respondents

- May make it too easy to answer without thinking

- May limit spontaneity

- Not best when

- asking for frequency of sensitive behaviors

- there are numerous possible responses

32

2. Drafting Response Categories

- If appropriate, include a dont know or not

applicable category - Response categories should be consistent with the

question - Bad Example Are you satisfied ? (Very,

Somewhat, Not too, Not at all) - Good Example How satisfied are you ? (Very,

Somewhat, Not too, Not at all)

33

Drafting Response Categories

- Categories must be exhaustive, including every

- possible answer

- Bad example Number of children 1, 2, 3

- Good example Number of children None, 1, 2, 3,

4 - Bad example How did you hear about the program

- Doctor (2) School (3) After-school program

- Good example (1) Health-care provider

(doctor,nurse), (2) School (teacher, school

nurse), (3) After-school program, (4)

Family/friends, (5) Other (specify)

34

Drafting Response Categories

- Categories must be mutually exclusive.

- Bad example

- Age 20-30, 30-40, 40-50, 50-60, 60

- Good example

- Age 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60

35

Drafting Response Categories RESPONSE

SCALES

- Respondents can generally remember a maximum of

only 5 responses unless visual cues are used - Number of points in scale should be determined by

how you intend to use the data - For scales with few points, every point can be

labeled (very satisfied, somewhat satisfied,

somewhat dissatisfied, very dissatisfied) - For longer scales, only the endpoints are labeled

(On a scale of 1 to 10 where 1 is Totally

Dissatisfied and 10 is Totally Satisfied)

36

Drafting Response Categories RESPONSE

SCALES

- Common scales

- Very, Somewhat, Not too, Not at all

- Very concerned, Somewhat concerned, Neither

concerned nor unconcerned, Somewhat unconcerned,

Very unconcerned - (1 to 10) Extremely dissatisfied Extremely

satisfied

37

3. Ordering the Questions

- Start with easy questions that all respondents

can answer with little effort - Should also be non-threatening

- Dont start with knowledge or awareness questions

- First questions should be directly related to the

topic as described in the introduction or

advance/cover letter

38

Ordering the Questions

- Segment by topic

- Ask about related topics together

- Salient questions (important to the respondent)

take precedence over less salient ones - Ask recall backwards in time

- Use transitions when changing topics give a

sense of progress through the questionnaire - Leave sensitive questions (e.g., income) for the

end - Put demographic questions at the end (most

sensitive) unless needed for branching/screening

39

4. Including Appropriate Instructions The Cover

Letter

- Introduction should indicate

- Who is conducting the survey

- The topics to be covered in the Q

- An assurance of confidentiality

- Any Internal Review Board stipulations

- Whether or not you mention length depends on

mode, topic, population - Must consider literacy levels

- Who to contact for additional information

40

5. Pre-Testing and Revising

- Essential part of every survey project

- Will inevitably need to make changes before

finalizing Q - May start by having staff/colleagues review Q

- Ultimately need to pretest on same types of

people as those who will answer the Q - Pretest same mode(s) as final plan (e.g., phone,

self-administered)

41

So Youve Collected Your Questionnaire Data

Now What?

42

Understanding Your Results

- Several factors that significantly affect your

results - History

- Passage of time (maturation)

- Selection

43

Factors That Affect Your Results

- History Things that happen in your community

outside of your project - Example A new state law changes eligibility for

services. - Strategies

- Use comparison information.

- Document, consider in interpretation and be sure

to report.

44

Factors That Affect Your Results

- Passage of time (maturation) People naturally

mature and change over time - Example You want to track height and weight

among children with developmental delays. - Strategies

- Use comparison information.

- Choose measures that can reflect program effects.

45

Factors That Affect Your Results

- Selection Who completes your questionnaire and

who is skipped or missed - Example You only collect data on families who

come to the clinic and consistently miss families

who are not showing up to their appointments. - Strategies

- Use your knowledge of your target population to

schedule data collection to maximize response,

and follow-up with groups that appear to be

missing. - If resources are limited, consider collecting

data from a random sample of program

participants, and invest your energy in finding

as many of those selected as possible. - Use comparison information.

46

Factors That Affect Your Results

- Random Sampling means that those who complete

your questionnaire are chosen at random, not

based on any individual or family characteristic,

group membership, or pattern of participation. If

people are selected randomly, it eliminates many

sources of bias in your results. - Examples of non-random sampling strategies

- The questionnaire is completed only by those who

attend an evening event at your agency. - Individuals are invited to participate through a

telephone call by the receptionist, who calls

those she knows are nice people likely to come in

(and, of course, who have phones). - The first 25 people to arrive complete a

questionnaire.

47

Factors That Affect Your Results

- Drawing a Random Sample

- Draw names from a hat

- Select every third or every fourth person on a

list of all program participants. - Use a coin toss to decide whether each individual

will be included. - Using a random sample may allow you to represent

your target population with a smaller number of

people. BUT, if you select respondents randomly,

you need to invest the resources to ensure

maximum response from those selected (or else

bias is re-introduced!).

48

Understanding Your Results

- History, maturation and selection are important

because they limit your ability to demonstrate

that your program helped participants to change - If everyone changed (history or maturation), a

finding that participants have changed as well

may not reflect the programs impact. - If your program participants were very different

from non-participants to start with (selection),

your results may reflect that difference rather

than program impact. - If the program participants you survey were

different from those you did not, your results

will not reflect the experience of everyone

involved (selection).

49

Understanding Your Results

- The impact of history, maturation and selection

can be better understood by - Knowing who, within your own target population,

is missing - Using comparison information from outside your

program

50

Knowing Who is Missing

- Use community level data to examine who is not

coming in for service and/or is excluded from

data collection. - Use baseline or pretest data not only for

individual comparison, but to see who is not

followed over time and who does not remain in

service.

51

Using Comparison Information

- Allows you to understand possible effects of all

three factors (history, selection, maturation) - Allows you to examine possible effects of

variations in level of participation in services

52

Types of Comparison Information

- A randomly assigned control group is the gold

standard, but usually not feasible for

community-based programs - Local comparison group

- Community, state or national data

- Absolute standard

- Change over time

53

What To Do With Results

- Considerations

- Original purpose of data collection

- Target audiences

- Quality of information

- Representativeness (selection is minimized)

- Completeness (the extent to which full

information is available for everyone at the

correct time points) - Comprehensiveness (extent to which the right

questions were asked of the right people)

54

Some Common Uses of Findings

- Improve services

- Advocate for service population

- Obtain funding

- Support replication

- Market services or organization

- Promote policy change

55

Some Possible Target Audiences

- Current funders (meet grant requirements)

- Potential funders

- Community members

- Potential recipients of services

- Other service providers

- Policy makers

- Project/agency staff

56

Data Analysis

- Simple is usually best

- Frequencies (counts)

- Cross-tabulations between two variables of

interest - Computer analysis is not always essential,

depending on the complexity of the questionnaire

and the number of respondents - Computer analysis can be simple, too. Look at

what is already on your computer (e.g., Excel) - Consider budgeting for someone to conduct data

entry and analyses

57

Sharing Your Findings

- Put findings into their proper context so that

they are interpretable. Briefly describe the

questionnaire, the process and who responded. - Be clear about limitations on conclusions you are

able to draw, based on data quality and your

ability to address factors such as history,

maturation and selection. - Questionnaire results can be very dry. Tell

stories to illuminate the findings and/or to help

describe the responding population. - Invite response and input from other service

providers, community members, and members of the

target population to check your findings and your

interpretations.

58

Sharing Your Findings Reports

- Short reports are more likely to be read

- Include an executive summary

- Use bullet points

- Use tables, charts and graphs as much as possible

- A picture is worth a thousand words

59

Where to Find More Information

- Bradburn, N, Sudman, S. and Wansink, B.. Asking

Questions The Definitive Guide to Questionnaire

design for Market Research, Political Polls,

and Social and Health Questionnaires. San

Francisco Jossey Bass, 2004. - Dillman, Don. Mail and Internet Surveys The

Tailored Design Method. New York John, Wiley

Sons, Inc, 2000. - Evaluation Resources on the AAP Web Site

http//www.aap.org/commpeds/resources/evaluation.h

tml - CDC Evaluation Resources

- http//www.cdc.gov/eval/resources.htmmanuals

- StatPac Designing Surveys and Questionnaires

http//www.statpac.com/surveys/contents.htm

60

AAP Staff Contact Information

- Healthy Tomorrows

- Nicole Miller nmiller_at_aap.org

- Karla Palmer kpalmer_at_aap.org

- CATCH

- Lisa Brock lbrock_at_aap.org

- Kathy Kocvara kkocvara_at_aap.org

61

Thank You for Your Participation!