In the1600s Sugar made Barbados the

1 / 32

Title:

In the1600s Sugar made Barbados the

Description:

In the1600's Sugar made Barbados the #1 English Colony. ... the West Indian islands of Barbados, St. Christopher, the Bermudas, and Jamaica. ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:236

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: In the1600s Sugar made Barbados the

1

In the1600s Sugar made Barbados the 1 English

Colony.

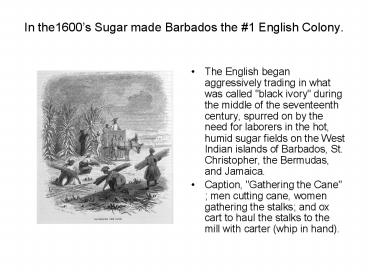

- The English began aggressively trading in what

was called "black ivory" during the middle of the

seventeenth century, spurred on by the need for

laborers in the hot, humid sugar fields on the

West Indian islands of Barbados, St. Christopher,

the Bermudas, and Jamaica. - Caption, "Gathering the Cane" men cutting cane,

women gathering the stalks and ox cart to haul

the stalks to the mill with carter (whip in

hand).

2

- During the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 10-12

million Africans were moved across the Atlantic.

Middle Passage (Euro-centric term)

3

- Most went to Brazil and the Caribbean. Only 3-4

came to U.S. - By the eve of the American Revolution, 50 of the

U.S. non-native population was African.

4

- African cultures were very diverse and complex.

- Africans were a form of immigrant. Although they

were forced, they came often as teens and early

adults. They brought with them their culture.

5

- Britain was the 1 slaving nation in the world.

- They brought 900,000 to the 13 colonies from 1820

to 1860 and over 2,000,000 total.

6

- Timbuktu was an intellectual and spiritual

capital and a centre for the propagation of Islam

throughout Africa in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Its three great mosques, Djingareyber, Sankore

and Sidi Yahia, were the center of Timbuktu's

golden age.

7

- 40 to 50 thousand Muslims were enslaved by the

British.

8

1806-1807 Omar Ibn Said in SC

- A daguerreotype photo held by Davidson College. A

Moslem from the Futa Tora area of present-day

Senegal, Omar Said was captured in warfare and

shipped to Charleston, S.C. in 1806/07, just

before the abolition of the slave trade. He spent

about 24 years enslaved in South and North

Carolina. He originally wrote his account in

Arabic in 1831, at around the age of 61 an

English translation appeared after his death in

1864. For details on Said and bibliographic

references to his life, see Jerome S. Handler,

Survivors of the Middle Passage Life Histories

of Enslaved Africans in British America, Slavery

Abolition, vol. 23 (2002), pp. 25-56.

9

Most slaves entered slavery as a result of

warfare.

- Caption, "chaine d'esclaves venant de

l'interieure" (chain/coffle of slaves coming from

the interior) shows six African men with two

armed guards. The author lived in the Senegal

region for about two years in the mid-to-late

1780s and made this drawing from his own

observations. He provides a detailed description

of the coffle and the movement of slaves from the

interior to the coast "Every year the Mandingo

traders, called slatées or Sarakole Sarakule,

Sarracolet, etc. Negroes, after having sold

slaves in exchange for European goods, leave with

necessary goods for the interior, toward Bambara

country.

10

No accounts of self-selling or family selling in

slavery. Slaves were captured and linked in

train-like COFFLES. They carried goods and were

coffled to the coast.

- The author lived in the Congo for six years,

1883-1889, and provides a vivid account of

slaving activities in the Congo basin. The

following excerpt describes the illustration

(captioned " A Slaver's Canoe") shown here, on a

tributary of the Congo River "I met dozens of

canoes . . . whose owners had come up and bought

slaves, and were returning with their purchases.

When traveling from place to place on the river

the slaves are, for convenience, relieved of the

weight of the heavy shackles. The traders always

carry, hanging from the sheathes of their knives,

light handcuffs, formed of cord and cane. The

slave when purchased is packed on the floor of

the canoe in a crouching posture with his hands

bound in front of him by means of these handcuffs

11

At the coast slaves were sold to African

leaders.The African leaders, in turn, sold the

slaves to European traders.Traders paid with

money, guns, beads, rum, fabric, etc.

- The king of Dahomey's levee," shows king seated

on his throne, with "amazons" (women soldiers)

and other members of his court on right, British

visitors (slave traders?) being entertained.

- The Europeans were often given drink and

entertainment by the African leaders to keep them

in port. The longer they were in port the higher

the price may go for the slaves due to

competition from other traders. - Europeans wanted to get out of port quickly. Keep

prices down and to keep away from yellow fever,

malaria, and other diseases that the Africans had

relative immunity to

12

- The English slave traders did their best to dupe

the native kings, and each native king did his

best to obtain the maximum amount of goods in

exchange for the slaves he had for sale.

13

Slaves were kept in forts along the coast.

- Caption along top "Cape Coast Castle, on ye Gold

Coast of Guinea." This seems to be one of several

variations of an engraving made by Henry

Greenhill in 1682 a copy is in the British

Library. See P.E.H. Hair, Adam Jones, and Robin

Law, Barbot on Guinea 1678-1712 (London, 1992),

vol. 2, after p. 392 and associated text. In the

1690s, an account of the Royal African Company's

forts in West Africa

- Surveyed in March 1756 by Justly Watson, Director

of Engineers, this colored manuscript plan shows

storerooms, warehouses, apartments for European

personnel, etc. In the upper right hand corner

(marked by the letter A) is the "women slave

yard." The inset contains a note saying "The

figures 1654 are upon the keystone of the arch to

the warehouse."

14

Slaves traveled through the door of no return

- Interior courtyard, where slaves were assembled,

and "Gate of No Return," the passageway through

which slaves were led to beach and from there to

waiting ships. (Photographed by Michael Tuite in

Ghana Aug. 1999).

15

to waiting boats that took them out to the slave

ships.

16

There were no ports or natural harbors along the

African coast.

- Photo looking west to site of former Elmina town,

destroyed in 1873 shows beach and surf. (Slide,

courtesy of Merrick Posnansky taken in Ghana,

1973)

17

Slaves were placed in the cargo holds of the

ships and packed tightly.

- Cross section of decks, "tight packing" of

slaves, storage areas. This ship sailed from La

Rochelle in 1784, picked up about 500 Africans

from north of the Congo River, and sold its

slaves in St. Domingue. Details on what was

apparently the only slaving voyage of this ship

can be found in D.Eltis, S. Behrendt, D.

Richardson and H. Klein, "The Transatlantic Slave

Trade

- Artist's reconstruction of "spoon" position in

which slaves were kept in the hold.

18

Revolts were attempted often, but rarely

succeeded.

19

Ships might load on anywhere from 200 to over 600

African slaves, stacking them like cord wood and

allowing almost no breathing room.

- Title and caption, "Representation of an

Insurrection on board a Slave-Ship. Shewing how

the crew fire upon the unhappy slaves from behind

the Barricado, erected on board all slave ships,

as a security whenever such commotions may

happen." Enlarged section from "Plan and Sections

of a Slave Ship," a fold out drawing included in

the Wadstrom volume. Wadstrom notes "It was taken

from a sketch which, with the explanation

attached, was communicated to him Wadstrom at

Goree in 1787."

20

The crowding was so severe, the ventilation so

bad, and the food so poor during the "Middle

Passage" of between five weeks and three months

that a loss of around 14 to 20 of their "cargo"

was considered the normal price of doing business.

- Enlarged section of original colored map, showing

North and South Atlantic, with bordering

continental areas in Europe, Africa, North and

South America.

21

The 14 to 20 of the Africans who died along the

way were often thrown overboard.

22

The surviving slaves entered the Charleston port,

being briefly quarantined on Sullivan's Island,

before being sold in Charleston's slave markets.

- The African American Coastal Trail. Marker

commemorating point of entry of countless

enslaved Africans. ... infantry regiment, active

during the Civil War, and the "pest houses" where

Africans were quarantined - After their horrific "Middle Passage," over 40

of the African slaves reaching the British

colonies before the American Revolution passed

through South Carolina. - Some refer to Sullivans Island as the Ellis

Island for African Americans. - Photo courtesy National Park Service.

23

Slaves were taken to the slave markets in Charles

Town

- Slave Market.Photo by Derrick R. Jordan.

24

where they were sold to the highest bidder.

- Slaves being sold, white onlookers and

purchasers. Sketch drawn by "our special artist,"

Mr. Davis who witnessed the scene shown in this

drawing. Accompanying Davis was W. H. Russell, a

correspondent for the London Times who gives a

detailed description of the slave auctions he

viewed while traveling through the South. The

location is not identified in the article, but it

was sent from Montgomery, Alabama

25

Families were often separated.

- Shows a man and woman (with child in arms) on

auction block, surrounded by white men. Article

in the ILN accompanying this "sketch by our

special correspondent" (G.H. Andrews) provides a

lengthy eyewitness description of slave sales in

Richmond, part of which is excerpted here "The

auction rooms for the sale of Negroes are

situated in the main streets, and are generally

the ground floors of the building the

entrance-door opens straight into the street, and

the sale room is similar to any other auction

room . . . . placards, advertisements, and

notices as to the business carried on are

dispensed with, the only indications of the trade

being a small red flag hanging from the front

door post, and a piece of paper upon which is

written . . . this simple announcement--'Negroes

for sale at auction' . . . ." From here there

follows a detailed description of the scene shown

in the illustration and the auction process (pp.

138 -140). A composite engraving, combining the

auction block and people on the right shown in

this image with the image of a slave being

inspected for sale (see image NW0027) was

published in the French publication

"L'illustration, Journal Universel (vol. 37

1861, p. 148), misleadingly giving the

impression that the scene is an original

depiction of a slave sale in South Carolina

26

- Men, women, and children being sold are displayed

on a raised platform. Illustration accompanies an

article ( "Sale of Slaves at Charleston, South

Carolina") by an English traveler who observed

the scene that is shown. He compares slave

auctions in South Carolina and Virginia. In the

latter, the auction is "hidden as much as

possible in out-of-the-way places" while in

Charleston, it takes place in a central part of

the city a detailed description of the

Charleston auction is given

27

Many of these slaves were almost immediately put

to work in South Carolina's rice fields. Writers

of the period remarked that there was no harder,

or more unhealthy, work possible.

- Men and women at work carrying bundles of rice.

"We wandered over perhaps 700 acres . . . . The

men and women at work in the different sections

were under the control of field-masters. . . .

The women were dressed in gay colors, with

handkerchiefs . . . around their temples. Their

feet were bare . . . . Most of them, while

staggering out through the marshes with forty or

fifty pounds of rice stalks on their heads . . .

indulged in a running fire of invective against

the field-master. . . .The 'trunk-minders', the

watchmen . . . promenaded briskly the

flat-boats, on which field hands deposited their

huge bundles of rice stalks, were poled up to the

mill, where the grain was threshed and separated

from the straw, winnowed, and carried in baskets

to the schooners which transported it to

Charleston... (King, p. 435). The Scribner's

article notes that the rice mill was located near

the wharf between Morris island and Sullivan

island so that the "rice-schooners" had easy

access to the mill.

28

- In fact, these Carolina rice fields have been

described as charnel houses for African-American

slaves. Malaria and enteric diseases killed off

the lowcountry slaves at rates which are today

almost unbelievable. Based on the best plantation

accounts it is clear that while about one out of

every three slave children on the cotton

plantations died before reaching the age of 16,

nearly two out of every three African-American

children on rice plantations failed to reach

their sixteenth birthday and over a third of all

slave children died before their first birthday.

Rice's macabre record of slave deaths has been

traced to two primary factors - one was malaria,

the other was the infants' feebleness at birth,

probably the result of the mothers' own chronic

malaria and their general exhaustion from rice

cultivation during pregnancy.

29

Many slaves brought the knowledge of rice

planting, cultivating, and harvesting with them

from Africa.

- The slave traders discovered that Carolina

planters had very specific ideas concerning the

ethnicity of the slaves they sought. In other

words, slaves from the region of Senegambia and

present-day Ghana were preferred. At the other

end of the scale were the "Calabar" or Ibo or

"Bite" slaves from the Niger Delta, who Carolina

planters would purchase only if no others were

available. In the middle were those from the

Windward Coast and Angola. - Carolina planters developed a vision of the

"ideal" slave tall, healthy, male, between the

ages of 14 and 18, "free of blemishes," and as

dark as possible. For these ideal slaves Carolina

planters in the eighteenth century paid, on

average, between 100 and 200 sterling in

today's money that is between 11,630 and

23,200!

30

African immigrants also brought their culture

including music, dance, basket making,

storytelling as well as the Gullah language.

African dance at the Kwanzaa Karamu. Photo by

William Green. n

31

The African culture has had a tremendous positive

influence on the development of South Carolina

culture.

- Caption "Musical Instruments of the African

Negroes," shows various percussion (e.g., drums),

stringed, and wind instruments. These

"instruments of sound," Stedman wrote, "are not a

little ingenious, all are made by themselves,"

and he provides a detailed description of the

items shown in the illustration. See Richard and

Sally Price, eds. Narrative of a five years

expedition against the revolted Negroes of

Surinam transcribed for the first time from the

original 1790 manuscript

32

- Once in South Carolina what was the lives of

these slaves like? How did they live? What did

they eat? What did their houses look like? How

did they prepare their food? What kinds of

possessions did they have? What did their pottery

look like? White masters had little or no

interest in recording these details for future

generations. Slavery was an economic issue and

the only details worthy of being consistently

recorded were those related to the value of their

slaves or the value of their production. The

daily lives of these new African-Americans was

probably poorly understood and certainly of

little importance to the planters. These are all

questions that were largely left to archaeology.

.

- Down by Hope Plantation, by Bernadette Cali.