Lecture 20: Macroevolution - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 23

Title:

Lecture 20: Macroevolution

Description:

Gradualism continental drift analogy; gradual changes in DNA sequences; ... Continental drift, which is the movement of the continents over time as huge ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:185

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Lecture 20: Macroevolution

1

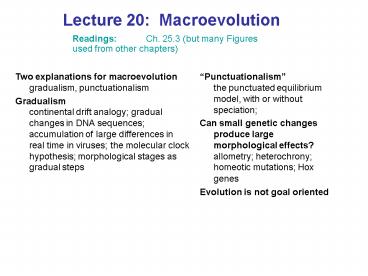

Lecture 20 Macroevolution

Readings Ch. 25.3 (but many Figures used from

other chapters)

Two explanations for macroevolution

gradualism, punctuationalism Gradual

ism

continental drift analogy gradual changes in DNA

sequences accumulation of large differences in

real time in viruses the molecular clock

hypothesis morphological stages as gradual steps

Punctuationalism

the punctuated equilibrium model, with or without

speciation Can small genetic changes produce

large morphological effects?

allometry heterochrony homeotic

mutations Hox genes Evolution is not goal

oriented

2

Charles Darwins explanations for macroevolution

gradualism His proposal is that macroevolution is

just the accumulation of the effects of

microevolution. This is essentially in part what

Darwin meant by descent with modification. We

now have a better appreciation that a large

fraction of evolutionary change may accumulate in

speciation events, if the punctuation model is

correct.

3

An analogy to show how small changes can

gradually accumulate to produce huge differences

continental drift. Continental drift, which is

the movement of the continents over time as huge

crustal plates on the surface of the earth move

with respect to each other. See Figs. 26.18-20.

Plates can separate, driving speciation, or slide

under one another (as Darwin in effect saw),

raising mountains.

4

Fig. 26.18. The crustal plates and their

patterns of movement. Note that South American

and Africa were once one continent, now divided.

5

We can actually see the gradual movement of

plates in almost real time now. Movement of the

big island of Hawaii, as measured using GPS

(Geographic Positioning System) From the Jet

Propulsion Laboratory (http//sideshow.jpl.nasa.go

v/mbh/series.html )

6

The point small, gradual changes add up to a lot

of plate movement given a few million years.

7

Back to a biological example, but one using rapid

but still basically gradual change evolution of

influenza virus. This example is from an

influenza virus hemagglutinin (coat protein) gene

study.

Texas 93 sequence at top

111111111122222222223333333333444444444 1234567890

12345678901234567890123456789012345678 caaaaacttcc

cggaaatgacaacagcacggcaacgctgtgcctggga caaaaccttccc

ggaaatgacaacagcacagcaacgctgtgcctggga 1 2 3 4

5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

China 85 sequence at bottom

time

Above are the first 48 bases of the gene - 16

codons that code for the first 16 amino acids -

in which there are 2 changes. There are

approximately 41 total changes between these two

sequences in the entire 987 bases. Note that this

is in the form of a DNA sequence for technical

reasons.

8

A really remarkable tree, showing the

accumulation of a lot of sequence difference, one

base at a time Haemaglutinin gene evolution in

influenza type A strains from 1985 - 1996. This

represents 1348 base substitutions total (with a

length of 987 bases)!

From Bush et al. 1999. Positive Selection on the

H3 Hemagglutinin Gene of Human Influenza Virus A.

Mol. Biol. Evol. 1614571465. 1999

9

The preceeding tree is a type called a phylogram,

in which the branch lengths tell us about the

amount of evolutionary change.

original

ATTAGATTAGCGATCGCTTTAATGGGGTAG

mutant 1

ATTAGATTAGCGATCGCATTAATGGGGTAG

mutant 2

ATTAGATTAGCGATCGCATTAATCGGGTAG

T to A

mutant 3

G to C

ATTAGATAAGCGATCGCATTAATCGGGTAG

T to A

10

But this kind of tree graph, in which the lines

do not tell us anything about the amount of

change along each branch, is called a cladogram.

ATTAGATTAGCGATCGCTTTAATGGGGTAG

ATTAGATTAGCGATCGCATTAATGGGGTAG

T to A

ATTAGATTAGCGATCGCATTAATCGGGTAG

G to C

ATTAGATAAGCGATCGCATTAATCGGGTAG

T to A

11

Figure 22.16 Comparison of a protein found in

diverse vertebrates

Over greater time spans, we see that gradualism

explains the large sequence differences between

the homologous genes of very different organisms.

12

Each dot represents the number of base

substitutions (changes) between a given pair of

species, out of about 3000 bp. In the

hypothetical example below, there are 2 changes

in 15 bp.

species A ATAAGGCGTATGGTA species B

ATAGGGCGTATGCTA

The molecular clock hypothesis - if gradualism

occurs at a regular rate, we may be able to date

events from molecular divergence.

sp. B

sp. A

millions of years

13

Fig. 24.14 A classic Darwiniam example of

gradualism for a morphological features - every

possible intermediate between the most simple and

the most complex structures are seen (as in

mollusc eyes).

14

But there is also evidence for what I am calling

punctuationalism - the idea that much change

happens in short spurts, and could be caused by

genes with large effects.

Fig. 24.13 Much debate has occurred on the issue

of whether macroevolution coincides with

speciation. But non-gradual evolution does not

have to coincide with speciation.

15

Fig. 24.15 Macroevolution often seems to involve

changes in the pattern of growth - of the pattern

of gene expression - of where genes are

expressed. Biologists have known for well over a

century that there are proportional changes in

the rates of growth of different parts of the

body. The study of these rates is called

allometry.

16

Fig. 24.16 Another critical aspect of

macroevolution is differences in timing of

growth of different parts - of the timing of gene

expression. This is called heterochrony. In

these salamanders, for example, foot growth

continues for a longer period of time in the

ground-dwelling salamander, resulting in longer

digits.

17

Figure 24.21 Paedomorphosis in an axolotl.

larval Tiger Salamander

adult Tiger Salamander

www.und.nodak.edu/org/ndwild/sally.html

Axolotl Tiger Salamander - larva with adult

reproduction

Fig. 24. 17 (current edition). A special case of

heterochrony is called - paedomorphosis - the

retention of juvenile characters in an adult.

18

Our understanding of how small changes in the

pattern of expression of genes can produce large

phenotypic changes has been increased by the

discovery of homeotic mutations - such as this

aristapedia mutation of Drosophila melanogaster,

in which the arista of the antenna develops into

a leg.

19

A class of homeotic genes that have been widely

studied in vertebrates are the Hox genes. (Such

genes contain a homeobox, which codes for a

particular protein domain that acts as a

transcription factor - it can bind to DNA in

particular sites and control gene expression).

Hox genes are very important in controlling early

development in vertebrates, and can be

illustrated by their effect on limb development.

20

Fig. 24.18 An example of a particular Hox gene

and its expression in limb buds in vertebrates.

21

Fig. 24.19

22

Figure 24.20 The branched evolution of horses

All phylogenies that include fossils show a

typical pattern of extensive branching and

extinction - not a linear progressive trend.

23

Lecture 20 Macroevolution

Readings Ch. 25.3 (but many Figures used from

other chapters)

Two explanations for macroevolution

gradualism, punctuationism Gadualism

continental

drift analogy gradual changes in DNA sequences

accumulation of large differences in real time in

viruses the molecular clock hypothesis

morphological stages as gradual steps

Punctuationalism

the punctuated equilibrium model, with or without

speciation Can small genetic changes produce

large morphological effects?

allometry heterochrony homeotic

mutations Hox genes Evolution is not goal

oriented