Course Outline Microeconomics 0 - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 17

Title:

Course Outline Microeconomics 0

Description:

The state (guarantees protection of property rights) ... people decide only how to allocate time between leisure and picking apples and ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:104

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Course Outline Microeconomics 0

1

Course Outline Microeconomics 0

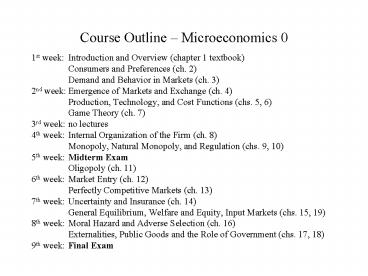

- 1st week Introduction and Overview (chapter 1

textbook) - Consumers and Preferences (ch. 2)

- Demand and Behavior in Markets (ch. 3)

- 2nd week Emergence of Markets and Exchange (ch.

4) - Production, Technology, and Cost Functions

(chs. 5, 6) - Game Theory (ch. 7)

- 3rd week no lectures

- 4th week Internal Organization of the Firm (ch.

8) - Monopoly, Natural Monopoly, and Regulation

(chs. 9, 10) - 5th week Midterm Exam

- Oligopoly (ch. 11)

- 6th week Market Entry (ch. 12)

- Perfectly Competitive Markets (ch. 13)

- 7th week Uncertainty and Insurance (ch. 14)

- General Equilibrium, Welfare and Equity, Input

Markets (chs. 15, 19) - 8th week Moral Hazard and Adverse Selection (ch.

16) - Externalities, Public Goods and the Role of

Government (chs. 17, 18) - 9th week Final Exam

2

Requirements and Grading

- Problem Sets 20

- Midterm Exam 30

- Final Exam 50

- Problem sets will be assigned regularly. They

will be discussed by the teaching assistants in

the exercise sessions. - Readings

- Textbook Schotter, Andrew Microeconomics A

Modern Approach. Second/Third Edition, New York,

Addison Wesley, 1997/2001. - Further Suggested Reading

- Nyarko, Yaw, 2001 Study Guide to Accompany

Schotter, A. Microeconomics A Modern Approach. - Varian, Hal R. Intermediate Microeconomics A

Modern Approach. Fourth Edition, New York,

Norton, 1996 or Third Edition 1993.

3

Announcements

- Extra Micro lecture Thursday, June 24th

- Micro instead of macro lecture on Tuesday, June

29th - Macro instead of micro lecture on Wednesday, July

7th - Teaching Assistants

- Vitezslav Babicky, Ekaterina Goldfain,

- Sylvester van Koten

4

1. Overview Economics and Institutions

- Institutions shape daily life, e.g. conventions

to drive on the right side, wages including

particular bonus systems, rules for decision

making in committees, etc. - Definition Institutions can be conventions like

tipping in a restaurant or sets of rules like the

political system, more loosely institutions refer

to large, established organizations - Economic Institutions refer to conventions

developed to solve recurrent economic problems or

sets of rules that govern economic behavior (and

organizations that serve an economic purpose) - Often these institutions are taken for granted,

but arrangements could be different, and in

different societies they often are.

5

- Microeconomics provides a technical apparatus for

understanding why specific institutions are the

way they are, i.e. it asks the question How do

individuals, in an attempt to maximize their

self-interest create a set of economic

institutions that structure their daily lives? - Conventional Microeconomics How are scare

resources allocated by one type of institutions

markets? - allocation problem microeconomics helps to

understand the question of allocation of scarce

resources in two ways - How should the resources be spent, given certain

objectives (Normative or welfare economics)

economics does not prescribe or give advise on

the objectives, though - How will the resources be spent, given a

description of the decision making process, i.e.

the institutions (Positive economics) - Positive question of institutional economics why

do we have the set of institutions we have? - Normative question of institutional economics

how can we design (or redesign) economic

institutions to increase economic welfare?

6

- Economic models are abstract representations of

reality, can be in the form of mathematical

models or analogies (in particular to games, to

be analyzed by game theory) - The model used in Schotters book

- Starts with primitive state of nature (no

production) - then gradually introduces markets, production,

firms, market entry, uncertainty (insurance

companies), asymmetric information, external

effects, public good problems - Three fundamental institutions are assumed to be

present - The state (guarantees protection of property

rights) - property rights (enhance the efficient use of

resources, avoid tragedy of the commons) - economic consulting firms (as a tool to examine

economic theory)

7

2. Consumers and their Preferences

- People differ, but there are certain regularities

of behavior. This part aims at identifying these

regularities and understanding what they tell us

about consumer preferences and decision making - primitive society without social institutions

- people decide only how to allocate time between

leisure and picking apples and raspberries and

which mixture to consume (everything also works

for more than 2 goods, but the graphs get ugly) - homo economicus (economic man) fictional

perfectly rational decision maker

8

- 2.1 The Consumption Possibility Set

- set of bundles feasible for the agents to consume

- not bounded from above, no economic restrictions

incorporated yet - assumptions

- divisibility goods are infinitely divisible

- additivity if a and b can be consumed, so can

a b - convexity if a and b can be consumed, then for

any 0? ? ?1, the combination c?a(1- ?)b can be

consumed as well

9

- 2.2 Rationality

- people are assumed to be rational, i.e. that

they have preferences over available consumption

bundles (notation aRb a is at least as good as

b) and that these satisfy specific properties - complete binary ordering for all pairs a,b aRb

or bRa holds. If both aRb and bRa hold, i.e. a is

exactly as good as b the agent is indifferent

between a and b, denoted aIb - Reflexivity for any bundle a, aRa

- Transitivity if aRb and bRc, then aRc.

- Why transitivity is important an intransitive

agent can be exploited.

10

- 2.3 The Economically Feasible Set

- The economically feasible consumption set is

bounded from above due to - time constraints assume that goods are only

consumed in daylight, 12 hours of daylight are

available and that it takes 4 hours to consume 1

unit good 1 and 2 hours to consume 1 unit good 2.

Due to divisibility and convexity the set of

economically feasible consumption bundles is

given by all bundles on or below the line of

bundles that take exactly 12 hours to consume

(Fig. 2.3) - budget constraints assume the agent has an

income of 6, the cost for 1 unit of good 1 is 2

and for 1 unit of good 2 it is 1. This leads to

the same constraint as above

11

- 2.4 Rationality and Choice

- A complete, reflexive, transitive preference

relation allows an agent to choose an optimal

bundle from the economically feasible set.

Without completeness, an optimal bundle might not

exist since some bundles could not be ranked.

Without transitivity, cycles can occur. - It is useful to express preferences by utility

functions each bundle is assigned a utility

number and the higher the number, the better the

bundle. Choosing the best bundle then amounts to

choosing the bundle that maximizes utility - utility need not be observable, but an agent with

preferences as above will behave as if he is

maximizing a utility function - required to be continuous, implies that for any

bundle there is another bundle that is exactly as

good. - counterexample lexicographic preferences (rank

countries on liberty first and on availability of

chocolate second)

12

- examples

- additive separable utility function U x y,

enjoyment from good x is independent of level of

consumption of good y - multiplicative utility function U x y, either

good produces utility only if the other is

consumed as well. - different types of utility function obviously

imply different behavior - cardinal utility not only comparison between

different utility levels is meaningful (higher

is better) but also difference (20 is twice as

good as 10) - ordinal utility only ranking meaningful, e.g. if

there are two objects and a is preferred over b

then both U1 with U1(a) 1000, U1(b) 0 and U2

with U2(a) 2, U2(b) 1 represent the same

preferences.

13

- 2.5 Psychological Assumptions

- We make the following assumptions about the

psychological makeup of the agents - Selfishness people judge allocations only in

terms of what they receive - Nonsatiation more of any good is always better,

i.e. an allocation that contains more of one good

and not less of the others is preferred. To

include economic bads (that reduce utility) in

the analysis, define as a good anything that

removes or prevents the bad - Convexity of Preferences diversifying is always

good, i.e. if aIb then any mixture such as ?a

?b is at least as good as a and at least as good

as b

14

- 2.6 Indifference Curves

- Indifference curve line through all bundles that

yield equal utility, i.e. through all bundles

between which agent is indifferent - Indifference map diagram that depicts an agents

indifference curves (Fig 2.7) - Each IC corresponds to one utility number, all

bundles on that curve yield that level of utility - Properties

- ICs dont slope upward (due to nonsatiation)

(Fig 2.8) - ICs cannot cross (due to transitivity and

nonsatiation) (Fig 2.9) - ICs farther from origin represent higher level

of utility (due to nonsatiation) (Fig 2.10) - ICs are bowed to the origin (due to convexity

and nonsatiation) (Fig 2.11)

15

- The marginal rate of substitution

- Assume we take -?x1 of good 1 away from the

consumer. How much of good 2 do we have to give

him to keep his utility level the same? - Let this be ?x2 . (Fig 2.12)

- The marginal rate of substitution is - ?x2/ ?x1

(actually the limit as these go to 0), the rate

at which the consumer would be willing to trade

good 1 for good 2. - the MRS equals the slope of the indiff. curve

- convexity of preferences implies diminishing

marginal rate of substitution, i.e. the MRS falls

when we move along IC - we have MRS (?U / ?x1) / (?U / ?x2)

16

- Different indifference curves represent different

tastes (Fig 2.13) - flat lines good 1 yields no utility (strict

nonsatiation violated) - straight lines perfect substitutes (constant

MRS) - Right-angled indiff. curves perfect complements

- Bowed-out indiff. curves non-convex preferences

(increasing MRS).

17

- 2.7 Optimal consumption bundles

- which bundle will an agent choose to maximize her

utility if she can choose from the economically

feasible set? - the optimal consumption bundle is characterized

by the indiff. curve being tangent to the budget

line (Fig 2.15) - slope of indiff. curve and budget line are

identical - MRS equals price ratio, i.e. rate at which agent

is willing to trade good 2 for good 1 is equal to

the rate at which she can trade good 2 for good 1 - MRS p 1 / p2 .

- Example Optimal tipping (violates selfishness

assumption, this demonstrates that the apparatus

can be applied to settings outside the basic

framework) (Fig 2.18)

![⚡Read✔[PDF] Microeconomics: Private & Public Choice (MindTap Course List) 17th Edition PowerPoint PPT Presentation](https://s3.amazonaws.com/images.powershow.com/10090948.th0.jpg?_=20240802129)